Halifax Explosion

Halifax Explosion: Film explores school for deaf

Nobody in the Halifax School for the Deaf was killed during the 1917 explosion

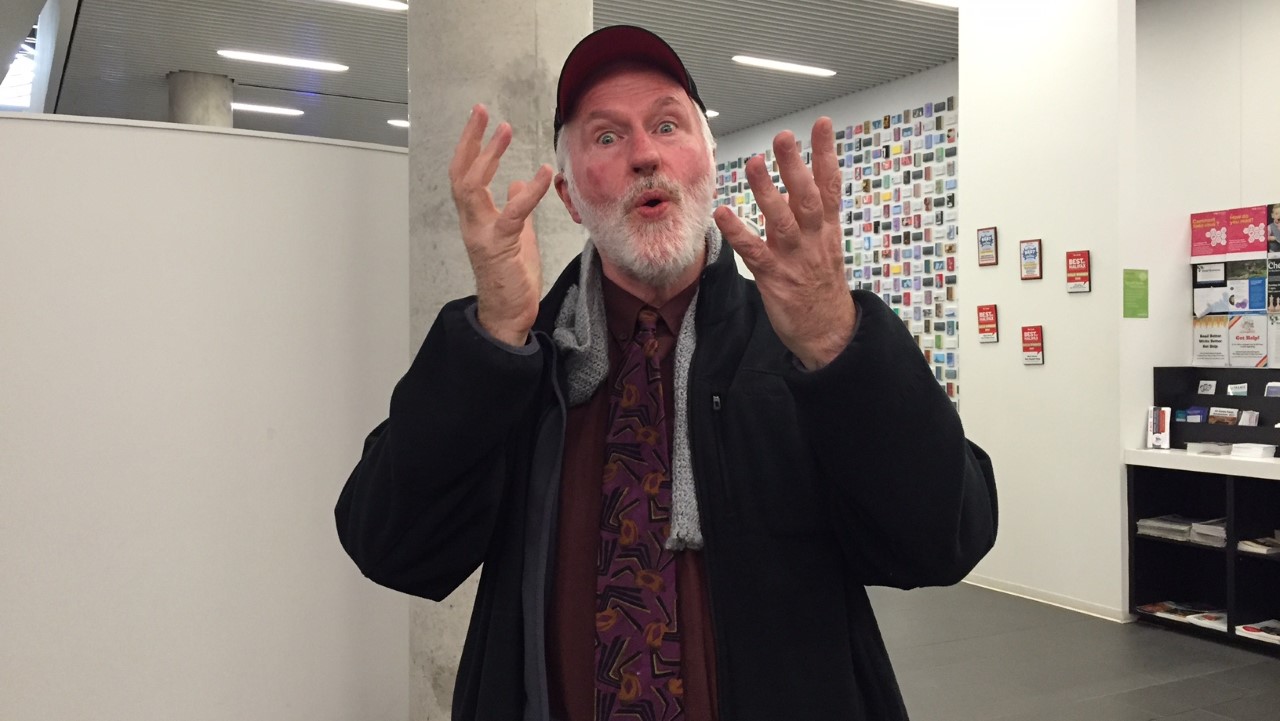

caption

Filmmaker Jim McDermott signs the story of the Halifax Explosion.

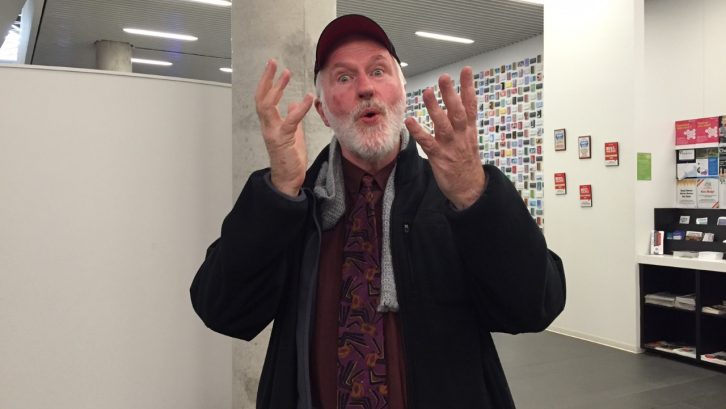

caption

Filmmaker Jim McDermott signs the story of the Halifax Explosion.One hundred years after the Halifax Explosion, another part of the story is being told: how students at the Halifax School for the Deaf survived.

On Tuesday evening, one day before the Halifax Explosion’s centenary, the Halifax Central Library showcased six local films about the 1917 disaster. The first was a live-action documentary about the Halifax School for the Deaf made by two deaf filmmakers. It was awarded best Canadian film at the Toronto International Deaf Film and Arts Festival.

Jim McDermott, the writer and on-screen narrator of Halifax Explosion: the Deaf Experience, warned his audience before the film, “it’s not the technology that’s a problem. There is actually no sound.”

An unconventional narrator, McDermott stood superimposed throughout the documentary, telling the story in sign.

The Halifax School for the Deaf stood where the George Dixon Centre is now located on Gottingen Street. The school was approximately one kilometre from the explosion in The Narrows, a waterway between the Halifax Harbour and Bedford Basin. The explosion was felt as far as Prince Edward Island, and 2,000 people were killed from the accident and the following snowstorm. Yet everyone at the deaf school remained unscathed, save for a few minor wounds from broken windows.

Both McDermott and director Linda Campbell are deaf. They learned the story of the deaf school’s survival as it was passed down within the deaf community, but there were no published accounts of the event.

Digging through archives, Campbell found that the story she uncovered was consistent with the stories told to her by the deaf community.

“It’s important that we have these stories to share with our deaf community,” Campbell signed after the screening. “It also opens up the door for people to see that we did have a tragic experience for those students. Many books and stories were published and nothing related to the deaf community.”

Short films

Following the documentary, the debuts of five animated shorts commissioned by the Atlantic Film Cooperative were screened.

In her animated short, Sincerely Yours, Mrs. Taylor, experimental animator Sam Decoste recounts a story originally sent in an email to CBC about a black grandmother’s struggle for survival in the aftermath of the explosion. The explosion left many black children orphans, and led to the creation of the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children.

Decoste said in the question and answer period after her film that she also had trouble finding information.

“The focus on history has been on a certain segment of society, and I found it really difficult to find information on communities that fell outside of that,” Decoste said.

The Atlantic Filmmakers Cooperative was commissioned $8,500 by the Halifax Regional Municipality to create art in commemoration of the explosion. The money was divided into $1,700 for each of the five animators to make their short.

Cooley said she thought animation could open a door to tell untold stories, in an interview before the screening.

“It just struck me that animation could be this new way to re-imagine some of the events, or to tell some of the stories that didn’t actually have any live footage connected to them,” Cooley said.