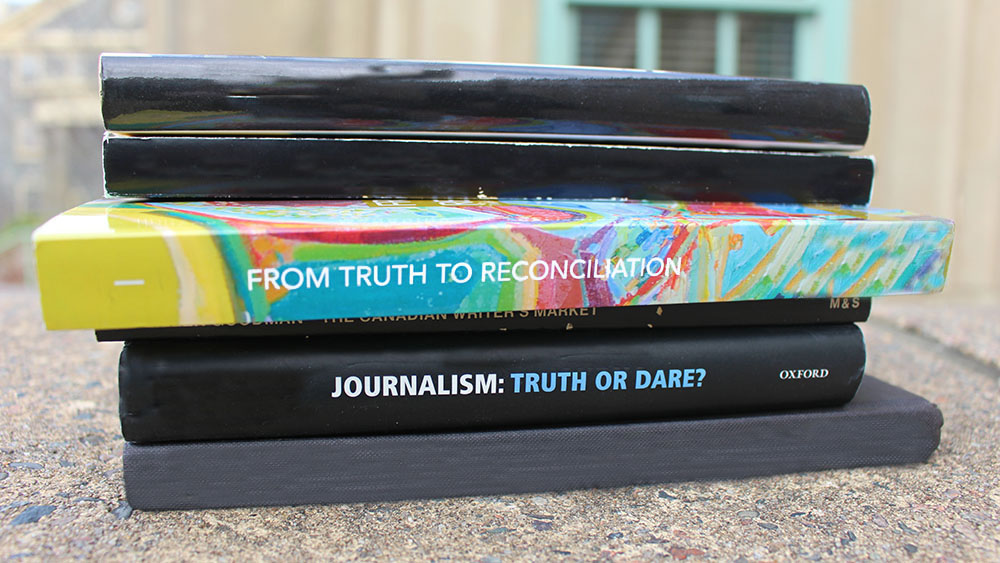

Journalism: Truth or Dare

caption

J-schools have been called upon by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to teach aboriginal history – so are they stepping up?

Karyn Pugliese was working as a teacher’s assistant in Canadian history at Carleton University in Ottawa when a comment from a student caught her off guard.

The class had been discussing a statistic about the high death rate of aboriginal children in residential schools.

“That is ridiculous. That can’t be true,” said a skeptical student.

“He just thought this must be made up … that this could not have happened,” says Pugliese.

It was that moment seven years ago that has stuck with Pugliese, who is now executive director of news and current affairs at the Aboriginal People’s Television Network.

To Pugliese, the skeptical student represents the many journalism students who go through school without learning about the history of Canada’s aboriginal populations.

But that may soon change.

Reconciliation in Canada

The 2011 National Household Survey reported that Canada is home to 1.4 million people of aboriginal origin.

Ry Moran, Director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, says the relationship between this indigenous population and the non-indigenous people of Canada was deeply fractured with the creation of residential schools.

The schools, dating back to the 1870s, were set up to eliminate the involvement of parents in the lives of First Nations, Métis and Inuit children, so they could be assimilated into Canada’s English-speaking Christian society. Over 150,000 children were placed, often without parental consent, in the schools.

“Residential schools are one of the most glaring examples of the breakdown of the relationship between indigenous and non-indigenous Canadians,” says Moran.

In 1996, the last of 130 residential schools in Canada closed.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), was created in 2008 to inform Canadians about residential schools and to inspire a process of reconciliation and renewed relationships between aboriginal and non-aboriginal Canadians.

In December 2015, the TRC released its final report and summary, which included 94 recommendations. These recommendations set out to redress the legacy of residential schools and to advance the process of Canadian reconciliation.

Among the recommendations was a call for journalism programs to require education for all students on the history of Aboriginal Peoples, including education on the history and legacy of residential schools. (Read the full wording of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendation in “The call to action” below.)

Linking media coverage and education

Coverage of stories about Aboriginal Peoples in Canadian media is an ongoing problem.

Nova Scotia journalist Maureen Googoo took on the problem in August 2015 by launching her news website kukukwes.com to tell stories from aboriginal communities in Atlantic Canada. She says stories about Aboriginal Peoples in the Maritimes have been missing from news outlets like CBC’s aboriginal digital unit.

“There is this gaping hole that is not being filled and I can go in and provide that coverage,” she says.

caption

Maureen Googoo conducts an interview for Kukukwes.com, which covers news about indigenous peoples in Atlantic Canada.Googoo sees a link between the lack of education journalism students receive about aboriginal history and poor coverage of aboriginal issues. She feels that learning to cover stories about Aboriginal Peoples should be required within basic journalism courses.

“If you’re training a bunch of journalism students to be reporters out there and to accurately reflect the history of Canada, then they need to know the history of aboriginal people in Canada and in the province where they’re learning their craft,” says Googoo.

Pugliese agrees that educating future journalists about aboriginal history is important because Aboriginal Peoples are intertwined with all aspects of Canada, including the economy, human rights, environment, resource development and taxation.

Pugliese says this is why it’s important for journalism students to learn the history of Aboriginal Peoples.

“Aboriginal people can change the course of history in Canada because they have the legal rights and power to do so,” says Pugliese.

Currently, many journalism schools across the country do not require students to deeply study aboriginal history.

But since the call to action, many schools are stepping up.

Taking action

Ryerson University in Toronto is currently working with Journalists for Human Rights, an international media development charity and non-governmental organization dedicated to helping journalists cover human rights stories, to bring aboriginal content to its journalism program.

Janice Neil, associate chair of Ryerson’s journalism school, says the call isn’t going unheard.

“It’s top of mind,” she says.

One of the ways the school is responding is by looking into creating an online elective that combines aboriginal content and journalism. Neil says the school has also confirmed a graduate course, starting in the 2016 winter semester, focused on producing stories about how the TRC’s other recommendations for reconciliation will create change in Toronto.

Other schools across Canada have also been working to meet the call.

Kelly Toughill, the director of the journalism department at the University of King’s College in Halifax, says there is an ongoing discussion at the school on how to meet the call. (Disclosure: This reporter is a journalism student at the University of King’s College.)

Toughill says she has distributed information about the TRC’s report to all journalism instructors and asked them to think about ways to respond to it.

She says King’s is looking at areas of its curriculum into which it can weave aboriginal content.

Students at King’s are able to take classes at neighbouring Dalhousie University. Toughill says she also plans to encourage journalism students to explore the new Indigenous Studies minor at Dalhousie.

“This is a touchstone of Canadian identity. The horror of residential schools is part of who we are – it’s a really important part of who we are – and understanding that, I think, is part of having a good education in Canada,” she says.

Toughill says she became aware of the call to action after the fall term had already begun, and says a deeper conversation on how to meet the call within the school’s numerous journalism programs will take place in early 2016.

Susan Harada, associate director of the journalism department at Carleton University, says Carleton will add a three-hour class on aboriginal issues and the media for first year students in the 2016 winter term.

Harada says the school believes following the recommendation is important, but can’t be done overnight. She says Carleton is still looking into how to respond further.

“We want to do this right,” says Harada

The University of British Columbia in Vancouver has been leading the way in integrating aboriginal content into its journalism program. Aboriginal content has already been weaved into the curriculum. For instance, students in UBC’s ethics class study Seeing Red, a book that looks at how Aboriginal Peoples have been portrayed in Canadian English-language newspapers.

UBC Professor and CBC news reporter Duncan McCue says including this content in the program is critical.

“Anyone in a Canadian newsroom or a freelancer pitching to Canadian publications is going to find they are covering indigenous issues at some point in their career. Indigenous issues are a pressing public policy matter in this country,” says McCue, who is Anishinaabe and a member of the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation in southern Ontario.

At the beginning of McCue’s Reporting in Indigenous Communities class, he gives students a cultural competency test. One of the questions McCue asks his students is how they feel about interviewing an aboriginal person. He says many students answer that they feel uneducated, nervous, and concerned about their lack of knowledge.

It’s McCue’s goal not only to teach future journalists how to report on stories about Aboriginal Peoples, but to ignite a passion in students to go out and find those stories.

Each year, McCue selects a theme, such as “health,” for his course, then sends students to nearby reserves to find a story that fits the theme. This year, students must dig up a story that relates to sexuality.

“I think they realize, over the course of working pretty intensively with First Nations communities over three to four months, that there are a lot of stories out there that need to be told, and that are really exciting and empowering to work on as a journalist,” says McCue.

Explore the map to find out how English-language journalism schools across Canada have responded to the call to action.

The ‘hang-ups’

Journalist and news publisher Maureen Googoo is all too familiar with the problems of Canada’s coverage of aboriginal communities. Like McCue, Googoo feels there is a lack of cultural understanding among non-aboriginal reporters.

“It’s something that I came across when I worked in mainstream media . . . There are a lot of non-aboriginal reporters out there who have hang-ups about going into aboriginal communities and talking to aboriginal people,” says Googoo.

She says if reporters aren’t comfortable going into the communities, they are less likely to cover the stories there.

A study done by Journalists for Human Rights looked at coverage of aboriginal issues in Ontario media between June 1, 2010 and May 31, 2013, and found that fewer than one per cent of all news stories produced during that time dealt with aboriginal-related issues. The study found that the number of stories about aboriginal communities rose when there were protests in those communities.

Googoo says coverage of protests in indigenous communities hasn’t changed since she reported on the Burnt Church crisis in New Brunswick over ten years ago. She says the only difference she sees is that social media has given Aboriginal Peoples a voice.

Aboriginal Peoples are very effective at getting the attention of news outlets through social media, says Pugliese, but the problem is with the coverage the issues then receive.

Googoo says the problem comes from how non-aboriginal reporters sometimes operate. “They parachute in, they get the stuff they need for deadline and they parachute out.”

Pugliese believes the first step in resolving the issue is to better equip future journalists with the knowledge to cover the stories.

‘Lip service’

But not all schools are eager to make changes right away.

Acting chair of the journalism department at Saint Thomas University in Fredericton, Philip Lee, said “It’s a challenge for us in journalism schools to cover all the stuff (journalists) should know to fill in the gaps,” in an article on the Aquinian, the school’s news website.

(Lee did not respond to our interview requests.)

Sean McCullum, fourth year journalism student at STU says he doesn’t feel the program has time to include aboriginal history. He says the school would have to take time away from other classes to integrate aboriginal content into its courses.

McCullum says courses at STU are meant to churn out journalists who will have the skills to do their own research and cover any topic, including stories on Aboriginal Peoples, fairly.

But fourth year journalism student Oscar Baker says making aboriginal history part of the curriculum at the school may help take some of the pressure off of him.

Baker is half Mi’kmaq and spent a portion of his life living on Elsipogtog First Nation. He says when aboriginal issues arise in class, he feels pressure from the professor to speak.

“It gets kind of burdensome that I have to field those questions that I don’t really know (the answers to) myself,” says Baker.

Baker says classmates look to him for insight. But Baker says he doesn’t always have insight to add.

“I can’t really be the voice for an entire people. I’m still learning myself,” he says.

Baker interviewed chair of the department, Phil Lee, for the Aquinian and says he believes Lee felt incorporating aboriginal content in the program was important.

“I think it’s something we need to respond to, certainly sooner rather than later,” Lee went on to say in the piece.

But Duncan McCue from UBC is tired of talk. McCue says just acknowledging that the issue is important is lip service. He would like to see all schools take action.

Hear Duncan McCue discuss the need for action on aboriginal education.

Knowing the ‘brutal realties’

Ry Moran, Director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, says it’s important that future journalists know the brutal realties of the country so the stories of Canada’s Aboriginal Peoples can be told.

“It’s really important that journalism schools take up this call,” he says, “because without it, we are going to be hard pressed to achieve reconciliation in this country.”

About the author

Payge Woodard

Payge is a master of journalism student at the University of King's College. She's interned for Bangor Daily News in Maine and freelanced for...