News for all

caption

How 1.5 million hearing or visually impaired Canadians stay up-to-date

In the last three years, administrative clerk Jennifer Gibson has answered more than 5,000 phone calls. She sits in a cubicle on the sixth floor of a downtown Halifax office building, facing two computer screens. And she faces a daily challenge – she is hard of hearing.

Gibson took the provincial government job because she had the qualifications. Still, accents, mumblings, and fast talkers can pose a problem. Her hearing aids only do so much. “We all have to make compromises,” she says.

Gibson also finds it difficult accessing daily news. She reads Facebook pages and news articles. And she doesn’t want to endlessly dissect webpages to find captioned videos.

A 2012 Statistics Canada survey revealed more than 874,000 Canadians have a hearing disability – almost as many people as there are in Nova Scotia. And more than 756,000 Canadians have a seeing disability – about the same as the population of New Brunswick.

Canadians 65 and older will double in number in the next 25 years. At 16.1 per cent, they exceeded children zero to 14 years old for the first time last year.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission has upped accessibility. Its Broadcasting Regulatory Policy in March 2015 was revised to boost this critical link to news and entertainment. The new policy, Let’s Talk TV, focuses on described video (a narration of visual elements like setting, appearance and body language) and closed captioning online.

Longstanding need

Rosalynd Ingraham, historic supervisor at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, recently welcomed special visitors. A family with young twin girls, both born deaf and sporting cochlear implants – electronic hearing devices in the ear – came to explore. They trailed along the first hallway, fascinated by Bell’s work.

Accessibility is older than telephones. Alexander Graham Bell taught his deaf students to speak during the day and invented at night (he invented the telephone at 28). Ingraham says he was a teacher of the deaf first, and an inventor second.

“In the middle 1800s people who were deaf had very few opportunities,” says Ingraham. “He believed if you were able to speak, you were able to get out in the world just a little bit more.”

The hearing and visually impaired often communicate through machines acting as a middleman. Braille and sign language have been around for more than a century. Later came programmed screen readers, talking book players, e-mail and instant messaging to solve technological disconnect. The hearing and visually impaired were the early adopters of hands-on tools.

News from the journalist

Michelle Hackman, a blind journalist working for the Wall Street Journal, does not struggle to read news. Apps for publications like the Journal and the New York Times are compatible with screen readers on both her computer and iPhone. “I think it’s definitely taken some persuasion to get people to care about accessibility,” she says. “Blind people are only a very small part of the market.”

Journalist Lisa Goldstein, a deaf freelancer in Pittsburgh, uses social media for interviews. Reading from a page is the best way for her to keep notes accurate. As for news, she often finds captioned videos – if they’re captioned at all – “terrible or delayed.”

This is frustrating. For example, “knowing there’s laughter and I haven’t gotten to the punch line yet,” says Goldstein. “Or seeing the mouths move and knowing it doesn’t fit with what I’m seeing onscreen.”

News access near and far

At CBC headquarters in Toronto, accessibility specialist Patrick Dunphy runs workshops with different CBC divisions to find out what barriers are stopping online accessibility. One exercise involves wearing mittens to surf the corporation’s programs. The goal, he says, is to frustrate participants with loss of movement. “If they can’t use their own content they’ve created, imagine the frustration an audience member feels.”

Soo Kim, CBC’s national senior director of digital operations, has participated in this workshop. The exercise is kind of funny, she says, but also reveals obstacles inadvertently placed in websites by news outlets, such as graphics that are not described and leave a visually impaired person unable to understand them.

When it comes to accessibility, Kim says the CBC is ahead of the journalistic pack. “What we see is they haven’t made it a priority as much as we have.”

She’s improving programs like CBC Watch and CBC Listen, the corp.’s long-form visual and audio experiences. As of fall 2016, CBC Watch has closed captioning and described video built into the online video player. CBC Listen will receive better social sharing and playlist features.

In 2015, CBC created daily online transcripts for its most popular talk radio show, the Current. These are typed versions of every word of each show, found on the website. According to a July report, a weekly audience of more than 2,000 viewers reads them. Another show, As It Happens, added transcripts in November. One Current documentary each month is also interpreted in American Sign Language.

The CBC, with these transcripts and documentaries in mind, applied for a grant from the Broadcasting Accessibility Fund Inc. The independent fund, founded in 2014, supports making broadcasting more accessible. The CBC has received two grants of $62,000 each – one for the Current’s transcripts and documentaries, and one for As It Happens and a more accessible audio player.

Dunphy wants to continue improving CBC accessibility. “If you’re Canadian, you’re a taxpayer. You contribute to CBC. It’s our responsibility.”

caption

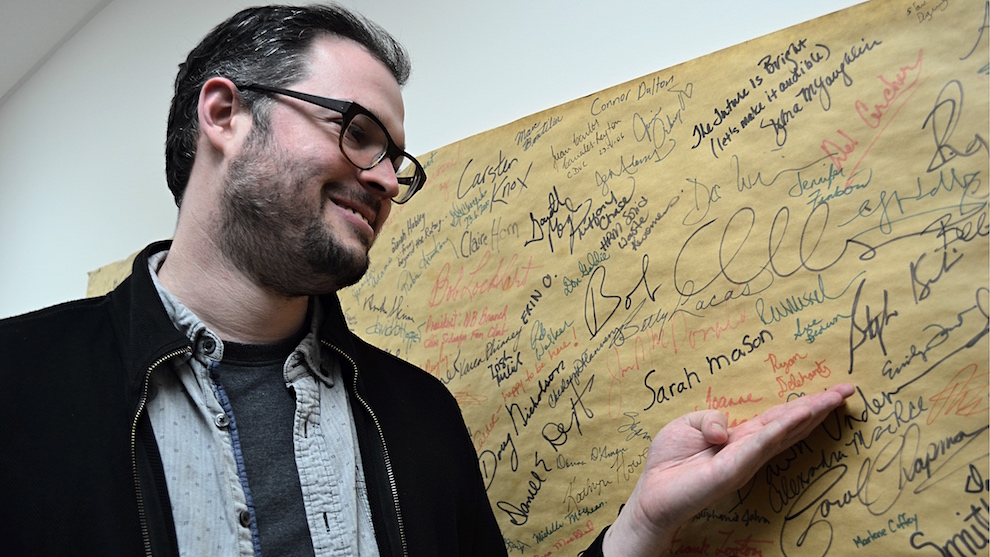

AMI volunteers sign an office banner. Ryan Delehanty, who started as a volunteer, points out his name.Accessible Media Inc.’s Atlantic assignment editor Ryan Delehanty has worked for AMI for more than nine years. He started as a volunteer, reading newspaper copy for recorded radio broadcasts when the company was known as VoicePrint.

Delehanty swapped in and out of different roles during the shift from radio to cable channels: AMI-audio, AMI-TV and AMI-télé (the French version). These share original, closed-captioned stories with description that automatically plays overtop (open described video).

The visually impaired rely on sound. Consider this dialogue.

“I can’t do this.”

“Yes you can, one big push.”

How can they tell if a baby is being born or a couch is stuck in an elevator on moving day without context?

People know Accessible Media Inc. (AMI) from this clever accessibility promotional ad.

Delehanty says there are “a lot of little things” that can make news more accessible. Speaker intros and graphics onscreen are often seen but not heard in regular newscasts. Information can also be narrated in a way that sounds natural, rather than bland.

“A lot of people don’t even realize it’s being made accessible,” says Delehanty. “Friends and family are more inclined to stay and watch.”

AMI’s Atlantic presenter Laura Bain, who is visually impaired, says natural-sounding audio invites everyone. Imagine watching a show but missing a subtle joke about a character’s facial expression that’s never explained.

“You don’t want the sighted audience to be seeing something that the person who’s blind or visually impaired will miss out on.”

Accessibility can be pinpointed on a world map with only a few tacks. The (U.S.) National Federation of the Blind’s Newsline has been delivering visual news by phone since 1995. It has expanded to offer more than 250 newspapers and magazines, an app, and a text-only website for screen readers. People can call for daily doses of the Associated Press or scroll the site for breaking CNN articles.

The BBC revamped its accessibility page, My web my way, in 2014. The page guides the viewer to the best online content for their disability. My web my way even includes a link to its website, CBeebies, which has accessibility friendly games with easier controls for adults and kids.

India made news accessible this year. Its first inclusive news app and website, Newz Hook, boils stories down to a few sentences. Sign Language videos are attached to most of the content. According to the website, the app aims to provide news “that matters to every one of us, but differently.”

A small victory

Jennifer Gibson still answers calls 35 hours a week. In 2013, insults from a fast talker forced her to take stress leave. “He proceeded to ask why the government would have a hard of hearing individual on the main telephone line,” says Gibson. In tears, she transferred the call to a woman with full hearing.

Three months later her request for an accessible Bluetooth model was granted. Gibson considers this a victory. The way she accesses news is part of a bigger picture – especially when looking for content online.

“We have a long way to go to make this world perfect for deaf people in a hearing world,” says Gibson. “We are in the year 2016. Technology is always improving and changing. There’s no excuse.”