The story of Turtle Grove

By Ava Coulter, Isabel Ruitenbeek and Julia-Simone Rutgers

The Signal

When the Halifax Explosion tore across the Narrows in 1917, it completed the destruction of a Mi’kmaq community often called Turtle Grove. That destruction had begun with the hostility and overt racism of neighbouring residents. Reporters Ava Coulter, Isabel Ruitenbeek and Julia-Simone Rutgers were assigned to chronicle the loss of that community, and found themselves grappling with how to tell the story.

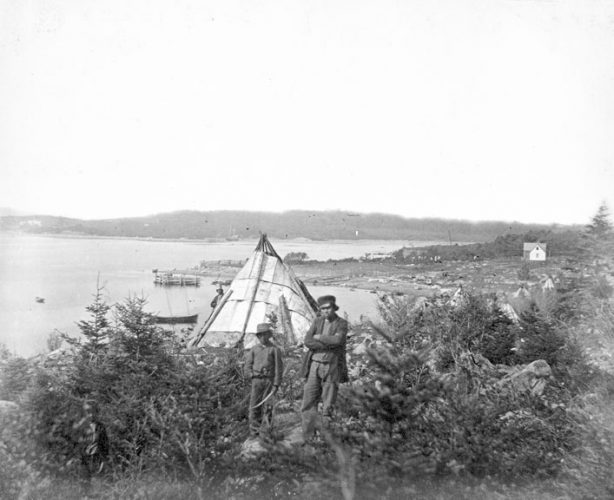

caption

Turtle Grove, a Mi’kmaq settlement on the Dartmout side of the harbour, now known as Tufts Cove.Catherine Martin, filmmaker and member of the Millbrook Mi’kmaq community, put a challenge to this group of reporters: she told us her story about her family at Turtle Grove, asked us to examine our own and look at where our stories intersect with hers.

What Martin calls the “Eurocentric approach” is what journalists learn as the only way to tell a story: stay objective, stay out of the story and attribute statements to the people who make them.

Yet if striving for objectivity results in the appropriation of stories and silencing of Mi’kmaq voices, perhaps it is time for journalists to do something different. We wanted to do something different. In writing this story, the struggle of how to tell it became as important as the story itself.

Two of us are white Canadians, one whose relatives were settlers on the prairies and the other is a first generation immigrant from western Europe. The other is a first generation immigrant with one black Caribbean parent and one white Canadian parent. Acknowledging our distance from the story is important in trying to tell the story in a new way.

“For 500 or so years, our stories have been told by non-native people, from a white perspective, from a colonized perspective, and from the way they want it told. And that’s not the truth,” said Martin.

Martin explains that centuries of non-Indigenous people telling Indigenous histories has resulted in a disjunction between the Mi’kmaq and their identity.

“It’s picking up the pieces, and only I can do that,” said Martin. “Because nobody has that right or the inside place that I have in my family.”

Martin added, “what I devote my life to is telling our stories. And telling them from my perspective. Telling them in the right way, from my place of my cultural property.”

The story we’re struggling to tell is about Henry Cope, Martin’s great uncle, and the Mi’kmaq community at Turtle Grove.

Cope, a 12-year-old Mi’kmaq boy, was at the Indian school in Turtle Grove on Dec. 6, 1917. He was killed in the Halifax Explosion. Martin has devoted years to finding out everything she can about him and her other family members who died that day. It’s a deeply personal and complex story, inevitably tied up in colonialism and racism towards the Mi’kmaq community.

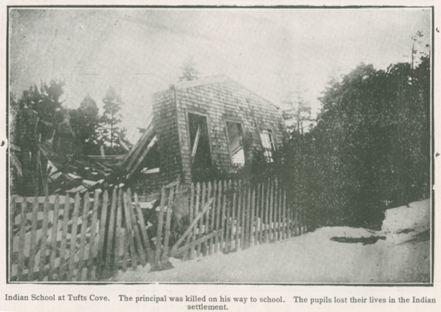

caption

The school at Turtle Grove where Cope was killed.Turtle Grove was a seasonal settlement comprised of a handful of Mi’kmaq families, seven wigwams and a school. It was located along the Dartmouth shore where the Nova Scotia Power generating plant now stands.

Martin said that the Tufts family, who owned some of the land, were far from welcoming. According to historian Jacob Remes, the white Farrell family, who also owned land, deemed the Mi’kmaq people squatters. The Indigenous people were “warned off the land” as early as 1879.

“I wish to know what you are going to do in reference to the removal of those Indians, who are a nuisance, a source of annoyance and most destructive individuals,” Farrell wrote to the department of Indian Affairs headquarters in Ottawa in January 1917.

The Mi’kmaq themselves had asked the Department of Indian Affairs to relocate them to Albro Lake to escape the toxic relations between settlers and Mi’kmaq. But the people of Albro Lake resisted; it wasn’t until three years later that the Mi’kmaq were finally scheduled to move—a week after the explosion.

Like so many others, the Turtle Grove residents went to the shore to watch the Mont Blanc burn. Moments later, they were hit by the explosion and subsequent tsunami.

After the initial shock,“the big thing that happens is the thing that doesn’t happen,” said Remes. “The school doesn’t get rebuilt, the settlement is prevented from being rebuilt.” The explosion had ultimately helped the government and settler neighbours raze the community—a goal they tried to achieve for years.

The Mi’kmaq survivors were forced to resettle, though some remained in the area.

Remes acknowledges the difficulty involved in telling someone else’s narrative. “I am a white person telling this story and, not only that, but I’m an American. I’m an outsider in every way,” he said. He sees a problem with non-Indigenous people telling contemporary Indigenous stories, but not histories.

He explains that he doesn’t want to live in a world where only French people can tell French history and African Americans cannot write about Shakespeare. He doesn’t believe history should only be written about by the race or ethnicity it primarily involves.

“I have very mixed feelings about it. I think there’s a danger to outsiders coming in and presuming to tell other people’s stories, but that’s always what historians do,” said Remes.

New ways of telling the story

On the 100th anniversary of the explosion, Martin is hosting a ceremony at the site of the old Turtle Grove community. On Saturday, Nov. 25, we joined a group of about ten people, mostly NSCAD professors and students, armed with gardening gloves, rakes and bags, and scoured the Turtle Grove area for garbage. They are the Narratives in Space and Time Society and they are cleaning the grounds so the Indigenous community doesn’t have to.

caption

Volunteers with the Narratives in Space and Time Society cleaning up Turtle Grove.“It’s bad enough we took their land,” said Barbara Lounder, “we may as well clean it up.” Lounder is one of the founders of NiS+T. Her work intersects with Martin’s in that both women are exploring Turtle Grove’s history, though in different ways.

“We basically just sort of shared our curiosities. For her it’s a very personal story and it’s her people. Literally her family, but also her people. For us, we’re not from that community; we’re settlers, and so we felt that our role was to kind of help.”

NiS+T leads walks around areas affected by the explosion and compiles photographs, videos and facts on their app, Drifts. Their walk “Across the Narrows” delves into the Dartmouth side of the explosion, including Turtle Grove. We did the walk, and Martin appears on the app in videos explaining where buildings used to be and what happened in certain locations.

Koumbie, director of the play Lullaby: Inside the Halifax Explosion, is also trying to tell the explosion story differently.

Lullaby is about three characters—one Mi’kmaq from Turtle Grove, one African Nova Scotian from Africville, and one white—who find themselves thrown together in the moments after the explosion.

“One of my mandates is to tell stories that haven’t necessarily been told before, about people that we haven’t necessarily heard about before,” she said.

Koumbie grew up in Halifax and had never heard of Turtle Grove or how it was affected by the explosion. For her, “it boils down to racism.” She believes the record keepers of history weren’t interested in marginalized communities, so their stories went untold.

Koumbie brings her own experiences to how she tells the Turtle Grove and Africville stories. “There’s something about having the experience of being a person of colour that, just in the room, can kind of change the narrative,” she said.

Koumbie and NiS+T are not the only ones looking for new ways to tell the story of Turtle Grove.

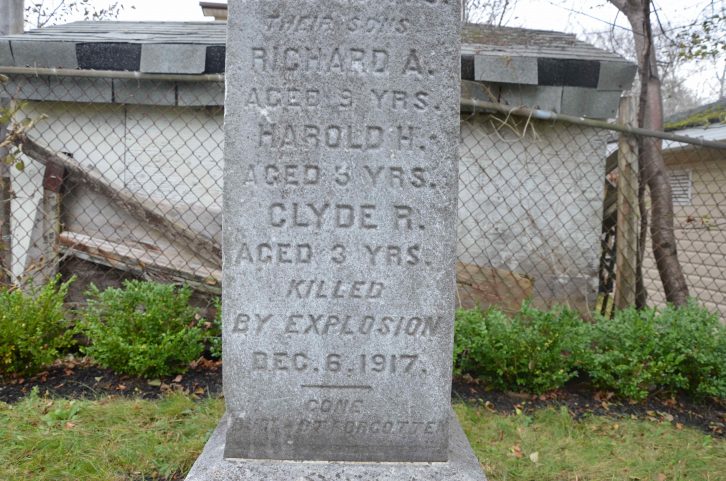

caption

A headstone showing the names of some Turtle Grove residents killed in the explosion.This fall saw the opening of ‘Kepe’kek from the Narrows of the Great Harbour’, a collective, youth-based photo project on exhibit at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia that commemorates the Mi’kmaq community destroyed by the explosion.

The aim of the project was to bring together Indigenous youth to research and tell the story of Turtle Grove, said Kehisha Wilmot, one of the photographers who participated in the project.

“A lot of the research I did was actually going back and talking to elders who had told me stories about the area growing up, and sitting with the land, realizing what’s currently there,” said Wilmot. “My focus was on what is still living and the idea that regardless of the amount of destruction that had been done, there was still so much there.”

Wilmot noticed that much of the recent media coverage about Turtle Grove neglected to tell the human stories of the affected communities, instead focusing on historic details.

“One of the things this project did was not only bring back the idea that people realize this area had been called something before Tuft’s Cove,” said Wilmot. “It was also bringing attention to the fact that we don’t know what we don’t know.”

Wilmot’s research led them to uncover a number of stories about survival, adaptation, trade and relationships with the land that were important to the Mi’kmaq communities in the Turtle Grove area.

“The water in that area had been such a massive trade route and because so much damage has come to that area from development, the waterways we used to connect inland communities to the harbour communities have been for the most part destroyed,” Wilmot recalls.

Other changes to the land, including the explosion, have changed the way the land is able to be used, Wilmot noticed. The tides are much higher now, and much of the land that the Turtle Grove Mi’kmaq lived on has now been developed.

“Where the drum would have been kept is parking lots and streets now,” said Wilmot.

Ultimately, Wilmot found a story of resilience in their time researching Turtle Grove. They cite the example of the mussels that live among the rocks in the water. Though the mussels should not be able to survive the toxin levels of the harbour water, their filtration systems have adapted for their survival. Wilmot believes this echoes the stories of the Dartmouth Mi’kmaq communities.

“So much said we shouldn’t still be standing there,” said Wilmot, “and look at us today—we’re still here.”