Online corrections: to reveal or not reveal

caption

With versioning technology, newsrooms could make updates to online articles visible to readers.Transparency is key, critics say, in making news outlets accountable

In October 2011, police arrested hundreds of people who carried banners and chanted as they marched on the Brooklyn Bridge, blocking the flow of traffic during an Occupy Wall Street protest.

The New York Times published an article online about the protest and arrest. Within 20 minutes, the Times updated the opening paragraph to no longer mention that the police officers had allowed the protestors onto the bridge. The change appeared to shift blame from the officers to the protestors.

The article caught the attention of Jennifer 8. Lee (8. is indeed her unusual middle name), a former New York Times reporter. Lee saw a problem with the Times changing articles without always indicating those changes to readers.

Eight months later, in June 2012, Lee and two friends, brothers Eric and Greg Price, headed to Cambridge, Mass. for the Knight Mozilla MIT hackathon, a two-day event where programmers, journalists and entrepreneurs work together to create data-driven projects.

As the trio brainstormed ideas, Lee brought up the Times’ article about the Occupy protest. Eric Price had also read about a recent article changed without notice given to readers. Influenced by these incidents, they decided to create a site to track changes to online articles.

While Lee says most changes to articles are “absolutely trivial,” she says there are sometimes cases, like the Times’ Occupy piece, where the updates are significant and influence meaning. If readers “want to go back and see, there should be a place where they can see changes and the different versions.”

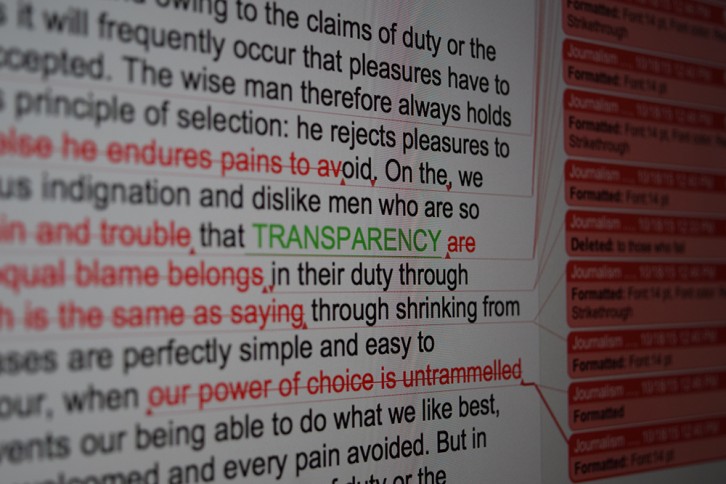

The site they created is NewsDiffs. They started their project focusing only on the New York Times. Over the course of two days, they created the bones of the site, a computer code that begins tracking each front-page story from the Times’ website fifteen minutes after publication. As the days go by, it continues to track at longer intervals. When the system detects changes in the copy, it reveals those changes by highlighting added words in green and deleted words in red. With a quick glance, readers can easily compare versions.

“We didn’t really realize when we were making it how frequently articles change,” says Eric Price. “We were hoping we’d see at least a few changes before the hackathon ended.” They were surprised to see dozens of changes to articles over the course of a few days.

After those first two days of programming, they spent a few more days making fixes. Price says it took about five days of work altogether. They also expanded the site to track articles from BBC, CNN, Politico and the Washington Post.

Price says the site now exists and updates on its own, automatically tracking articles. He puts in a bit of time every few months to fix any glitches.

Wikipedia does it

The kind of tracking NewsDiffs does is known in the tech world as versioning. Essentially, versioning means keeping track of all changes made to computer software or, in the case of online journalism, a web page. Software developers use versioning as they update programming. Any organization running a website can internally track the various versions.

Wikipedia is one popular website that uses versioning. On every Wikipedia page, readers can select a tab at the top to view the editing history.

NewsDiffs creators aren’t the only ones interested in using versioning in journalism. Scott Rosenberg, a long-time journalist living in Berkeley, Calif. and co-founder of Salon, is another advocate.

caption

Rosenberg says news outlets should be transparent about changes made to online article.In June 2010, Politico published an online article about Gen. Stanley McChrystal, a top U.S. commander in Afghanistan. U.S. President Obama had criticized McChrystal for comments made in the presence of a Rolling Stone reporter. The Politico article stated that Michael Hastings, author of the Rolling Stone article, was more likely to publish McChrystal’s remarks because Hastings was a freelancer rather than a beat reporter. Politico suggested a beat reporter would be less likely to publish controversial comments, because they wouldn’t want to burn bridges with a source. Politico removed the paragraph the next day without any explanation or corrections note. Readers criticized Politico for its lack of transparency.

In response to the controversy, Rosenberg wrote a post on his website calling for news outlets to use versioning technology to make the versions — the stages an article goes through after publication — publicly available.

A 2011 study by the Pew Research Center found 72 per cent of Americans believe news media try to cover up its mistakes. Rosenberg believes versioning would improve reader trust, and help “hold the journalism profession accountable.” However, he makes it clear versioning wouldn’t replace corrections notes.

“It doesn’t lift the onus on the editors and the reporters,” he says. “If you ran a big story and got it wrong in a big way, you still owe it to your readers to come clean about that in a larger way than simply putting up a new version of the story.”

Readers complain

Every day, Kathy English reads emails from Toronto Star readers. The Star’s public editor since 2007, she considers and responds to reader complaints. Among calls for corrections and other concerns, English says readers often ask the Star to remove a story from its website.

“I say no three times a week to requests to unpublish,” says English. The Star will only consider unpublishing from the web in cases of serious legal concerns, or if a subject can make a strong case that their life is in danger.

The Star has clear policies in place for this and many other matters related to online publishing. In her eight years as public editor, English says she has worked to improve the way the paper approaches corrections and transparency in online news.

English has written about the need for newsrooms to have consistent policies for online corrections, both in her role as public editor, and as a member of the Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ) ethics advisory committee. In 2011, English chaired a panel that wrote a CAJ position paper calling for transparency when editing published stories, and expressed the need for news sites to have corrections notices readers can easily find.

The CAJ position paper came at a time when many people were discussing online corrections practices. With the advent of online journalism, newspapers have had to work to adapt corrections policies for online articles. In 2010, Sabryna Cornish, an assistant professor in media studies at North Central College in Napperville, Ill., looked at online corrections policies on 19 major U.S. newspapers’ sites. She found 47 per cent of the newspapers had no corrections policies available online. Cornish argued newspapers needed more consistent policies for making online corrections. While Cornish hasn’t crunched the numbers since then, she thinks many news outlets still have work to do in improving their policies.

English, on the other hand, says she has seen a big improvement since she chaired the CAJ panel in 2011. She doesn’t think there are the same problems with lack of transparency with online corrections as she saw a few years ago. “I think that people thought online would be somewhat different, that they could just sort of go over to a web editor and say ‘oh can you change this’,” says English. “What I’m seeing is that everyone in the newsroom gets it now.”

caption

Some news outlets adapt corrections policies for online articles.Versioning is not something on English’s radar, and she says making every small change visible to the public is not something the Star is considering. She says as long as journalists are transparent about changes that do impact meaning or content, there is no need to track every change.

“I think in principle (versioning) sounds wonderful,” says English. But it is not a priority. She explains that it is “not something that can be done within our publishing system right now, so you have to look at a technical solution for doing it.”

“Newsrooms have to consider how they’re going to use their resources.”

How to handle updates in a 24-hour online news cycle is something all newsrooms must consider. Margaret Sullivan, the New York Times’ public editor, writes about the need for improved transparency. She has not suggested using versioning.

The Times has noticed NewsDiffs, though. In 2012, a few months after Lee and the Price brothers created the site, Arthur Brisbane, the Times’ public editor at the time, wrote a column commending NewsDiffs for doing what the Times does not do for itself.

“(T)he journalistic sausage-making process on display is fascinating, raises many questions for critics to seize upon and, I believe, puts pressure on The Times to offer its own accounting of its coverage,” wrote Brisbane. He encouraged the Times to implement a similar system for itself, writing that a “more comprehensive archive that retains all significant versions of an article (and all corrections) would send readers a strong message that The Times is committed to full transparency and accountability.”

In September 2015 NewsDiffs tracked the changes made to this New York Times article.

Despite the mention in the Times, NewsDiffs and versioning are new to many people in the world of journalism, including Shauna Snow-Capparelli, chair of journalism at Mount Royal University in Calgary. She is also co-chair of the CAJ ethics advisory committee. Snow-Capparelli sat on the 2011 CAJ panel that English chaired.

Snow-Capparelli says journalists have a responsibility to increase reader understanding. She doesn’t want journalists to hesitate to fix small grammatical errors if it improves the clarity of a story. “We don’t want to put up any barriers to being correct,” she says. Still, as long as changes don’t affect the meaning of a story, she doesn’t think they need to be tracked.

Those who support the use of versioning say they don’t want to stop journalists from making updates. One of those people is Scott Maier, an associate professor in the school of journalism and communication at the University of Oregon. He thinks versioning could be beneficial, though he’s only heard about it recently.

“I think it’s a very interesting thing, especially for myself and others who like to sit back and see how a story is transformed,” says Maier. “So that’s a very bold and I think constructive way to provide transparency.

“Not only is it okay, it’s essential for the new form. We now report news as it breaks, rather than send it to your editor, send it to your copy editor, have a final editor look at it and print it the next day. Well, that’s history.”

Caught in the act

The fast pace of online journalism is one reason Salon co-founder Rosenberg is an advocate of versioning. There are often opportunities to correct grammar and improve sentence structure after publication, he says, and journalists should be transparent and make those changes.

Rosenberg refers to a feeling every journalist knows: looking at an article the day after publication and seeing a sentence you could have written so much better. Rosenberg says a main reason journalists often don’t update their work is they “feel there’s something wrong with it. You know, that it’s somehow shameful or inappropriate to improve our product.”

He says improving stories doesn’t have to be shameful, as long as news outlets are open about those changes, rather than being caught in the act by readers.

Rosenberg applauds NewsDiffs, but he wishes there wasn’t a need for a third party site to hold news outlets accountable.

“It’s sad to me to see journalists and editors in the position of the public figure, the politician who has to be monitored by this independent website for wrongdoing,” says Rosenberg. “That’s not the best way to earn the public’s trust. You earn that trust by building systems that are accountable and show a sense of openness and confidence.”