Oceans

How to balance economic and environmental interests in Nova Scotia’s waters

Three speakers from Rhode Island explain their strategy

caption

Grover Fugate speaks at the ‘Planning for the Oceans of Tomorrow’ event Wednesday evening.

caption

Grover Fugate speaks at the ‘Planning for the Oceans of Tomorrow’ event Wednesday evening.As Nova Scotia struggles to balance new tidal energy projects with the needs of local fisheries, research methods proposed by a trio of Rhode Island experts may provide a solution.

“We are the Ocean State and so the waters off of our shores are really important to who we are,” said Jennifer McCann, director of U.S. Coastal Programs at the University of Rhode Island. McCann was speaking about “marine spatial planning” — or how their state manages and plans the waters that border it.

Around 60 people filed into the Potter Auditorium in Dalhousie’s Kenneth C. Rowe Management Building to hear the researchers speak. The event was a joint effort between Dalhousie and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Vice President for Oceans at WWF-Canada, and former MP of Halifax, Megan Leslie helped organize the event. In an introduction, she said she was puzzled the first time she heard about marine spatial planning.

“Until someone described it to me as ‘land use management for the sea.’ And then I got it.”

In the similar vein of land management, marine spatial planning seeks to balance government regulation and development with the needs of conservation and tourism.

Currently, in Nova Scotia, there are several new tidal energy projects underway and recently a $4B offshore wind farm was proposed off the coast of Yarmouth.

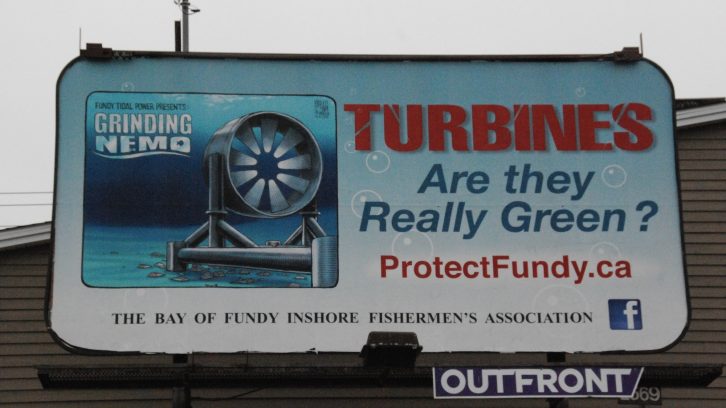

However, this past week the Bay of Fundy Inshore Fisherman’s Association paid for anti-turbine billboards that read “Grinding Nemo,” that went up around the municipality. The group also went to court in the fall to halt installation of the turbines, but a judge ruled against them.

caption

One of the Bay of Fundy Inshore Fisherman’s Association’s billboards can be found at the corner of Oxford Street and Bayers Road in Halifax.In 2007, Rhode Island was facing similar challenges as Nova Scotia is now.

As a tourist destination, Rhode Island hosts prominent sailing regattas and is known for its beautiful coastlines; the state’s waters are also busy with fishing and shipping lanes.

The state of Rhode Island has made a firm commitment to combatting climate change, and the company Deep Water Wind is proposing building large-scale offshore wind farms.

The researchers said, since tourism is an integral part of their economy, keeping the turbines away from land was important. Fishermen also raised concerns about disruption to their regular fishing lanes.

The research conducted lead to the creation of the Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP) in 2010.

The plan was the result of mapping out the waters surrounding their state. They avoided tourist and residential areas. They also tracked important species habitats, such as the North Atlantic right whale, to avoid disruption.

Fishing boats were tracked in the remaining area to map the most used fishing routes. This allowed the researchers to target specific zones best suited for turbine development — all in less than a year.

“The three fisherman’s groups that showed up to the (Ocean SAMP) hearing all testified in favour of the project,” said Grover Fugate, executive director of the Rhode Island Resources Management Council. “We wouldn’t have had any of that without that planning process in place.”

As a result of the Ocean SAMP research, Rhode Island has five turbines above the water to date, generating energy for their state. Eventually Deep Water Wind aims to have hundreds of offshore wind turbines in the area.

The researchers who spoke Wednesday evening stressed that Rhode Island’s success was a result of collaboration.

“Everyday was a new concern,” said McCann about the planning process. The team would receive phone calls from locals, all the way up to the governor, and met with communities regularly.

“We made sure, through every part of the process, that stakeholders, whether they be tribal members, fisherman, marine trades, (and) municipalities, that they had input and they had a seat at the table, just as much as the researchers did,” said McCann.