What’s left of Nova Scotia’s Postmedia newsrooms?

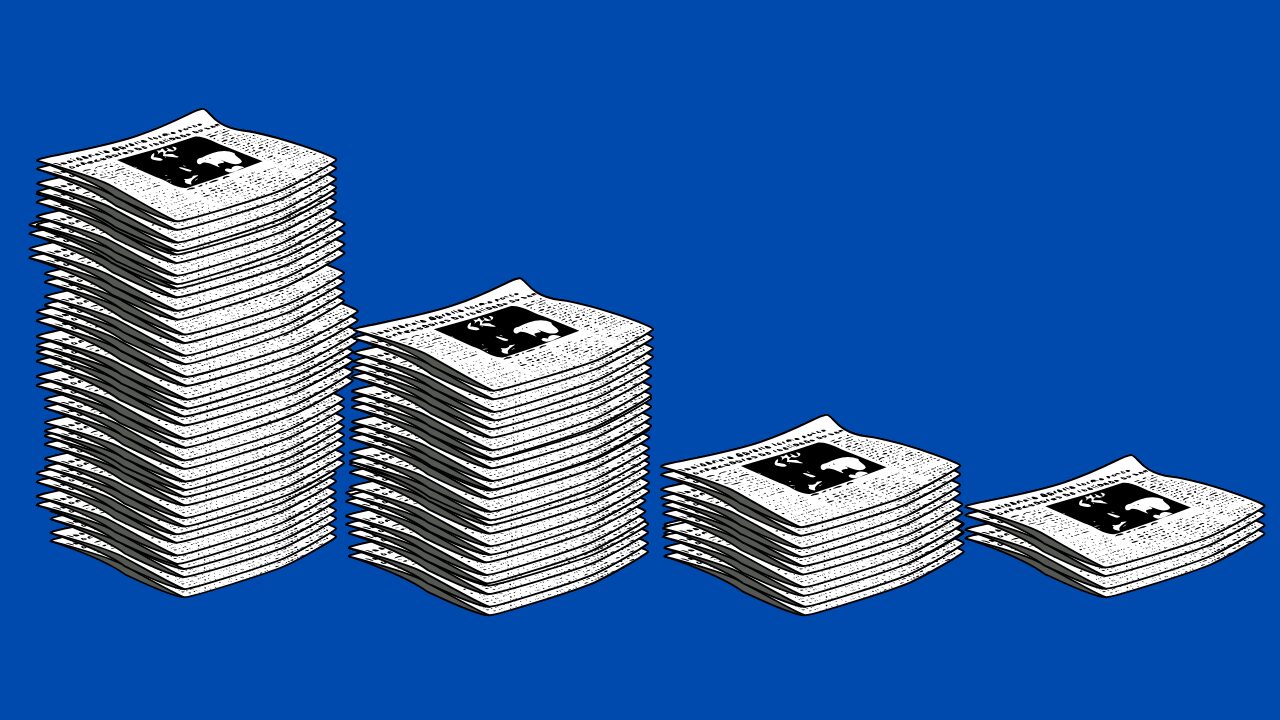

caption

Graphic made on Canva.Local journalism is changing with 2024 takeover of SaltWire newspapers

The old Cape Breton Post building on George Street in downtown Sydney sits empty and for sale, with no recent hopes of a buyer. It stands like a fossil of what once was – a monument to the decline of local news.

Across Atlantic Canada, bustling newsrooms are shrinking or being shut down altogether. In August 2024, SaltWire Network, Atlantic Canada’s largest newspaper chain, sold its more than two dozen publications to Postmedia, an American-owned, Toronto-based media giant that owns over 100 news outlets nationwide. The sale has raised questions about the future of local journalism.

caption

Former Cape Breton Post journalist, Barb Sweet, was laid off after Postmedia’s acquisition of SaltWire.For journalists like Barb Sweet, the change wasn’t just a business headline. While visiting family in Pictou County, she received a letter that would change her decades-long career: she’d been terminated.

“I’m trying to, like, obviously take the high road, but the only way I can put it is, if you’re exceptional, you don’t expect to find yourself in that position,” says Sweet, reflecting on the sudden layoffs, which happened soon after the purchase.

Sweet had worked at the Post for about a year and a half, after decades of reporting at The Telegram in St. John’s, N.L. Like many of her colleagues, she was now suddenly out of work.

SaltWire bankruptcy

The warning signs had been there.

In March 2024, Fiera Private Debt Fund filed documents in the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia pushing SaltWire into bankruptcy, claiming mismanagement had left the Halifax company owing them $32 million. The filing also revealed $2.6 million in pension payments owed and more than $7 million in outstanding HST payments to the Canada Revenue Agency. SaltWire filed for creditor protection.

When the news broke, Sweet said she remembers looking at a colleague sitting at a desk across from her and muttering, “holy heck.”

This wasn’t the first glimpse of trouble. In 2015, labour disputes broke out at Saltwire’s flagship paper, the Halifax Chronicle Herald. It began when management locked out press workers. In January 2016, more than 60 newsroom staff members went on a strike that lasted 19 months, until August 2017.

Despite claiming financial hardship, the Herald created SaltWire during the strike and bought nearly two dozen east-coast newspapers.

Sweet was one of five people cut from her newsroom in 2024, leaving seven others behind. She was also among the more than 60 SaltWire employees laid off at the time of Postmedia’s acquisition.

“I knew people who suddenly were out of a job, who I know were exceptional at their job and put all their heart and soul into it,” says Sweet. “My heart was broken by it.”

Postmedia CEO Andrew MacLeod told The Canadian Press that the cuts were necessary to save the company from bankruptcy and create “efficiencies” that could stabilize the newspapers’ future.

In a letter to readers, he said: “Change is difficult, but we at Postmedia believe with deep conviction in a positive, sustainable and vibrant future for news media in the Atlantic provinces and across Canada.”

caption

The old Chronicle Herald building on Joseph Howe Drive in Halifax in 2017.

caption

The former Chronicle Herald building on Joseph Howe Drive on Oct.1. The Herald sign was recently taken down.A former news bastion

Newsrooms that once were busy and full of life across Atlantic Canada have continued to dwindle in size. Former Herald vice-president and chief operating officer Ian Scott was laid off in November 2024. He estimates the newsroom is now “in the vicinity of half” the size it was before Postmedia’s takeover.

When Scott first started at the Herald in the 1990s, the paper held a much different place within the Halifax community.

“It was a much more significant part of the media landscape,” says Scott. “… It was owned by the Dennis family, and the Dennis family took a lot of pride in sort of maintaining that as a bastion against the homogeneity of news that was coming in from other directions.”

But that bastion couldn’t withstand the pressures facing all newspapers. And while layoffs hurt careers, they also hurt coverage. Where reporters once filled pages with local events and meetings, small newsrooms can no longer keep pace.

“When I was a young reporter … We covered all the councils … school board meetings, hospital board meetings and everything exhaustively, and you know, there were private radio newsrooms and all that sort of thing,” says Sweet. “You knew what was going on in your local community, but you know that hole has become so massive now.”

At the Herald today, most sports stories are written by reporter and Halifax Typographical Union president Willy Palov. Of the Herald’s five top sports stories on their website from one recent weekend, four were written by him.

“We just changed how we approach coverage because, 30 years ago, when I arrived at the Herald, we had a massive sports staff and the philosophy was to cover everything,” says Palov. “That’s not really practical anymore.”

Palov is now the only full-time sports reporter, which means he has to be selective about what he covers. Many community-level sports go unreported.

“That is the downside,” says Palov. “Some of that grassroots coverage is hard to do now. Not just down to high school, but up and coming athletes or even levels as high as university sports. We can’t cover all of that.”

Investigative journalist Tim Bousquet, founder of the Halifax Examiner, doesn’t hold back on his criticism of Postmedia’s purchase. After the sale, he wrote that there is no way to replace the community news coverage the SaltWire papers once provided.

More than a year later, his outlook hasn’t changed, and he’s not hopeful it will improve.

“I think we’re just starting to see, or we haven’t yet seen, the full impact of the change because Postmedia has been moving relatively slowly to make wholesale changes, but I think those are coming,” Bousquet said in an interview with The Signal.

Postmedia did not respond to The Signal’s request for comment on the newsroom changes.

Collapse of local news

The decline of local news coverage is not just a media problem – it’s a civic one.

A report done this year by the Public Policy Forum, in partnership with the Rideau Hall Foundation and the Michener Awards Foundation, found that the collapse of local news poses a threat to Canadian democracy.

The report studied five communities, including Bonavista, N.L., where no news outlet remains. Residents reported they couldn’t access locally-sourced information about local candidates during the federal election.

According to the report, 70 per cent of Canadians surveyed said more local news would have helped them feel better informed.

April Lindgren is the founder and co-director of the Local News Research Project, a combination of content analysis and digital mapping which explores the role of local news across Canada. She started the project back in 2008, when local journalism was the “poor stepsister of journalism research because people were more occupied with national and international coverage.”

“There is a great awakening to the fact that reporters, editors and news organizations that told people’s stories to each other at the community level, that held local power accountable, built a shared sense of community, were extremely important and part of the critical infrastructure of a successful city, town, or rural municipality,” Lindgren said in an interview.

According to a report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the proportion of Canadians with one or no local outlets has doubled since 2008, rising from three per cent of the population to seven per cent today.

Lindgren says the decline in local news can’t be solely blamed on corporate acquisitions of smaller outlets.

“There are bad actors at every level of the news system,” says Lindgren.

Data from a Local News Map shows that of 603 local news outlets in 338 Canadian communities that have closed since 2008, 440 were local newspapers. Of the total, 325 were direct closings and 115 were closings due to mergers.

caption

A mix of recent Halifax Chronicle Herald papers, ranging from September to October 2025.‘Everybody bought the Post’

For readers like Cape Breton native Leanne Birmingham-Beddow, the loss to local reporting is personal. She’s been a lifelong Cape Breton Post reader and has watched the paper thin out, despite its popularity in the community.

“The Cape Breton Post, it’s like Pepsi in Cape Breton,” says Birmingham-Beddow. “Everybody bought the Post.”

Lately, even her 82-year-old father has stopped reading.

“He’s like, ‘There’s nothing in it.’ All it is now is ads, and there are no stories, there are no sports, there are no different areas,” said Birmingham-Beddow from her home in Hammonds Plains.

While flagship papers that were staples in the Atlantic Canadian news environment are not what they once were, this could be an opportunity for independent outlets to step up.

Advocate Media is based in Nova Scotia, publishing four newspapers and more than 20 magazines, and has a strong focus on hyperlocal journalism and community stories.

Sweet recently started an editing position at the Pictou Advocate, one of Advocate Media’s outlets.

“The Advocate puts out like 20 pages, aside from puzzles and stuff, but it’s a 20-page, 100 per cent local paper every week,” says Sweet. “… That’s probably five days of a daily paper right there in one edition.”

Birmingham-Beddow has also found herself reaching for more hyperlocal news outlets.

“These little papers, all of a sudden, it seems like it’s breathed new life into them, and they’ve got more people covering stories,” says Birmingham-Beddow. “They’re hyperlocal – the Inverness Oran, thicker than I’ve ever seen it and full of ads.”

In March, the CBC radio program Ideas highlighted the Oran as a news outlet thriving in a declining news industry. One of the main reasons they are successful is that they focus on what is important in their small community, and people are interested in stories that are close to home.

Oran reporter April McDonald said one of the reasons for the paper’s success is that they have a younger generation wanting to be involved.

“They want to not only be a part of the Oran, they want to learn about their local history, and they want to tell their stories, but they also want to tell their neighbours’ stories,” said McDonald in an interview for Ideas.

April Lindgren said she is inspired by local journalism.

“Every year when I look at the list of award-winning journalism that’s been done across the country, I look at the stories … and I think, ‘Wow, that’s so important and so powerful,’ ” said Lindgren.

“That continues to inspire me to do whatever I can to help increase the supply, availability, and access to journalism.”

About the author

Marielle Godfrey

...

Leave a Reply