Journalists defend ‘fluff’ news

caption

Colleen Jones and her cameraman watch a strongman lift eight hay bales at once.Should community & human interest stories be taken seriously?

Striding through a farmer’s field, Colleen Jones sinks the heel of her pink snakeskin pump into a fresh dump of cow manure. The veteran broadcaster shrugs and carries on, her focus intent on eight tightly packed bales of hay. She’s in Lunenburg to report on one of the world’s strongest men. As her cameraman films, a balding, heavily muscled man bends over, lets out a deep grunt, and with biceps bulging lifts all eight bales at once. A nearby flock of chickens offers some celebratory-sounding clucks.

caption

Colleen Jones jokes around with one of the world’s strongest men.Jones has spent most of her 28-year career at the CBC covering sports and weather – hurricanes, curling championships and 10 Olympic Games. She says she finally found her niche about six years ago – reporting community and human interest stories. She hasn’t pitched another type of story since.

In a medium flooded with round-the-clock and breaking news, community and human interest stories like Jones’ are often overlooked. Fellow journalists, readers and viewers dismiss them as non-news and fluff. Critics argue they’re trivial and lack substance, depth and relevance.

Jones is quick to counter these claims. She says reporting hard news is boring and restrictive. One by one, she lists fluff’s qualities: it’s a positive alternative to hard news, it fosters creativity and emotion, and it highlights ignored stories. For Jones, stories like the strongman’s are the ones worth telling.

“I look at hard news as the low fruit on the tree: it’s easy to get,” she says. She rhymes off examples of hard news: storms, court cases, gas leaks.

“Crafting a story, a human interest story, and getting to the nuts and bolts in a minute forty-five – (now that) requires storytelling.”

Jeanne Moos stands on a busy Manhattan street corner, a camera and sound man poised over her shoulder. As a torrent of business suits rushes past, Moos stops certain characters – cigarette smokers, hat-wearers and grumpy-looking people – and gets their opinion on pop culture.

It’s all part of her offbeat news segment aired daily on CNN. Recent stories have ranged from the paparazzi at George Clooney’s wedding to salsa-dancing children.

Moos hasn’t always covered this type of news. She spent the better part of the ‘80s and ‘90s as CNN’s correspondent at the United Nations, covering hard news, including the first Gulf War. Fifteen years in that role “put her over the edge.”

“Hard news was a waste of me,” Moos says. “You can’t really let yourself go and write creatively, which is what I do best. By the end of it, I just wanted a more creative outlet.”

In the mid-’90s she began reporting quirky news stories. The response to these pieces, she said, has been overwhelming. “I can’t tell you the number of people that come up to me, and they actually say thank you,” she said. “I’m embarrassed.”

Moos’ pieces air weekdays in the final minutes of The Situation Room, the hard-hitting news program hosted by Wolf Blitzer.

“I kind of like to think of (my stories) as the dessert,” Moos said. “There’s all this horrible, terrible, bloody gory news for about 55 minutes, and then there’s two minutes of something absurd or funny at the end.”

Kevin Donovan remembers sitting in the parking lot of an Etobicoke, Ont., apartment complex, staring at a cellphone video. He and a fellow Toronto Star investigative reporter watched the screen in awe as they saw Toronto Mayor Rob Ford smoking crack cocaine.

It was May 2013. What followed was five months of unanswered phone calls, denials by the Ford family and slammed doors until the mayor admitted to smoking crack.

Donovan can spend months on the trail of a single story. He says the time commitment and the level of investigation set his work apart from fluff pieces.

While he enjoys reading soft news, he says hard news is much more difficult to cover. “There’s an element of risk that you will not be able to prove the story,” Donovan says. “If you’re going out to talk to the world’s strongest man, you’re going to get that story. It’s not that hard.”

To illustrate, he contrasts covering the strongman story to arriving at a murder scene. “You’ve got to go and try to talk to the family (of the murder victim). That’s very difficult… more difficult than going to talk to the (strongman) in Lunenburg.”

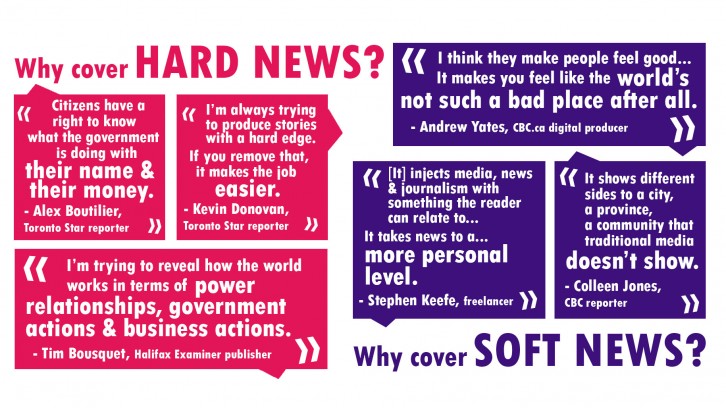

caption

Journalists have a variety of reasons for covering soft news and hard news.

He says each story he writes needs a combination of hard news and human interest to produce good journalism people want to read. His coverage of privacy laws, for example, not only details the new laws, but how they impact readers’ privacy on Facebook and cellphones.

“I have a duty to find a human interest side of what I’m reporting,” Boutilier says. He thinks human interest reporters have a similar responsibility to include a hard news angle in their stories.

Boutilier says reporting hard news takes more work. “A lot of people in Ottawa or in the legislature of Nova Scotia or at city hall work very, very hard to get out information that (politicians) don’t want out there,” he said.

“I don’t take kindly to suggesting the kind of news I do is low-hanging fruit.”

Halifax investigative reporter Tim Bousquet says fluff pieces fail to challenge news readers and viewers. In 2013 he was nominated for a Michener Award, the top prize in Canada for public service journalism, for his story on former Halifax Mayor Peter Kelly mishandling a family friend’s estate. Bousquet now runs the online publication the Halifax Examiner.

Though Bousquet sees a place for fluff in journalism, he says those types of stories must be done right. “It’s got to be engaging. It’s got to be interesting. It’s got to be smart,” he said. “Unfortunately, I don’t often come away from a piece feeling that way. I think a lot of it is bad reporting.”

He blames tight time constraints placed on reporters, some of whom are expected to turn in several stories each day. Producing fluff stories, he said, is a quick and easy way to “satisfy the bosses,” but their satisfaction does not encourage journalists to go deeper into issues.

“The whole point of the free press is to be challenging society,” Bousquet said. “If you’re not pissing people off, you’re not doing it right.”

Stephen Keefe’s editor wanted him to write about the opening of a Montreal café full of cats. Keefe decided to take it one step further. He went to the café after drinking a cup of tea laced with magic mushrooms.

Keefe documented every psychedelic moment in an article for Vice Media. Inside the café and stoned on mushrooms, he observed the walls around him start to shine and the baristas who begin to look like cartoon characters. A cat even struck up a conversation with him about the death of Joan Rivers.

A freelance journalist, Keefe writes about community and human interest matters. While he acknowledges criticisms of these stories, Keefe says he’s not trying to be hard-hitting or politically relevant.

“It offers an insight, it offers entertainment, and I argue that those things are equally as important as being factually informed,” he says. “I’m not claiming to change the world.”

These types of stories allow Keefe to tackle alternative viewpoints and issues he says are ignored in mainstream media.

Take his piece on squeegee punks. Keefe spent an afternoon on the streets of Montreal, wiping car windows for spare change with several young men sporting tattoos and clad in torn denim. While the story focused on Keefe’s individual interactions with these men, it highlighted the broader social issues of mental illness, poverty and addiction.

Similarly, Jock Lauterer turns to community and human interest news to read stories he’s never seen. The University of North Carolina journalism professor acknowledges these stories are not news in the “hard-breaking, breathless TV” sense, but he says they contain vital information.

“It’s the kind of (story) where you are sitting there reading the paper and you holler up to your wife, ‘Hey, did you see this? This is important’.”

Lauterer teaches a course on local, community reporting at North Carolina and has written four textbooks on the topic, including three editions of Community Journalism.

He says journalists should cover community and human interest stories to hone their skills. “Everybody wants to go to National Geographic, Sports Illustrated and the New York Times,” Lauterer said. “You’ve got to realize that before you get there, you’ve got to be able to go the county fair and take great photographs of the pig races.”

On the internet, community and human interest stories are among the most popular types of news. The growing presence of websites known for fluff news, namely BuzzFeed and the Huffington Post, demonstrates these stories’ popularity.

caption

Soft news reporter Cyril Lunney takes a spin at the Discovery Centre in a segment for Halifax’s CTV Morning Live.

Traditional hard news websites saw much smaller increases. CNN’s traffic grew 34 per cent, while the Washington Post and the New York Times increased by 20 and 15 per cent respectively.

The Toronto Star’s digital editor, Erika Tustin, says human interest and community stories contend with hard, breaking-news articles as the site’s most popular stories.

A 2000 study of television, news magazines and newspapers by Harvard’s Shorenstein Center demonstrates the growing interest in soft news. In 1980, human interest stories accounted for 11 per cent of all stories. As of 1998, these types of stories made up 26 per cent.

Colleen Jones leaves the strongman’s house and drives along Nova Scotia’s South Shore, turning up her radio to hear the two o’clock newscast. As the announcer reads the headlines, she offers her critique.

“I don’t find that news. I don’t care,” said Jones, after hearing a piece about Halifax’s new chief librarian. “I would rather hear about (the strongman) who is now in the Guinness Book of World Records any day.”

Jones believes the news does not reflect reality. She lists the types of people who make the news: corrupt politicians, murderers, and child pornographers.

“How many of those people do you know? None. In your world, when you look out, what do you see? You see good, beautiful, awesomeness.”

There’s a reason community and human interest remain the only types of stories Jones pitches.

“Your town and your place are full of these characters that make a place livable … and give it the heart and soul of a community,” she said.

“Those stories are not just important to get out. They are vital to get out.”

Watch a day in the life of fluff journalist Cyril Lunney, co-host of Halifax’s CTV Morning Live.

Editor’s note: This story was written and reported by Oct. 17, 2014.