2(b) or not 2(b)

caption

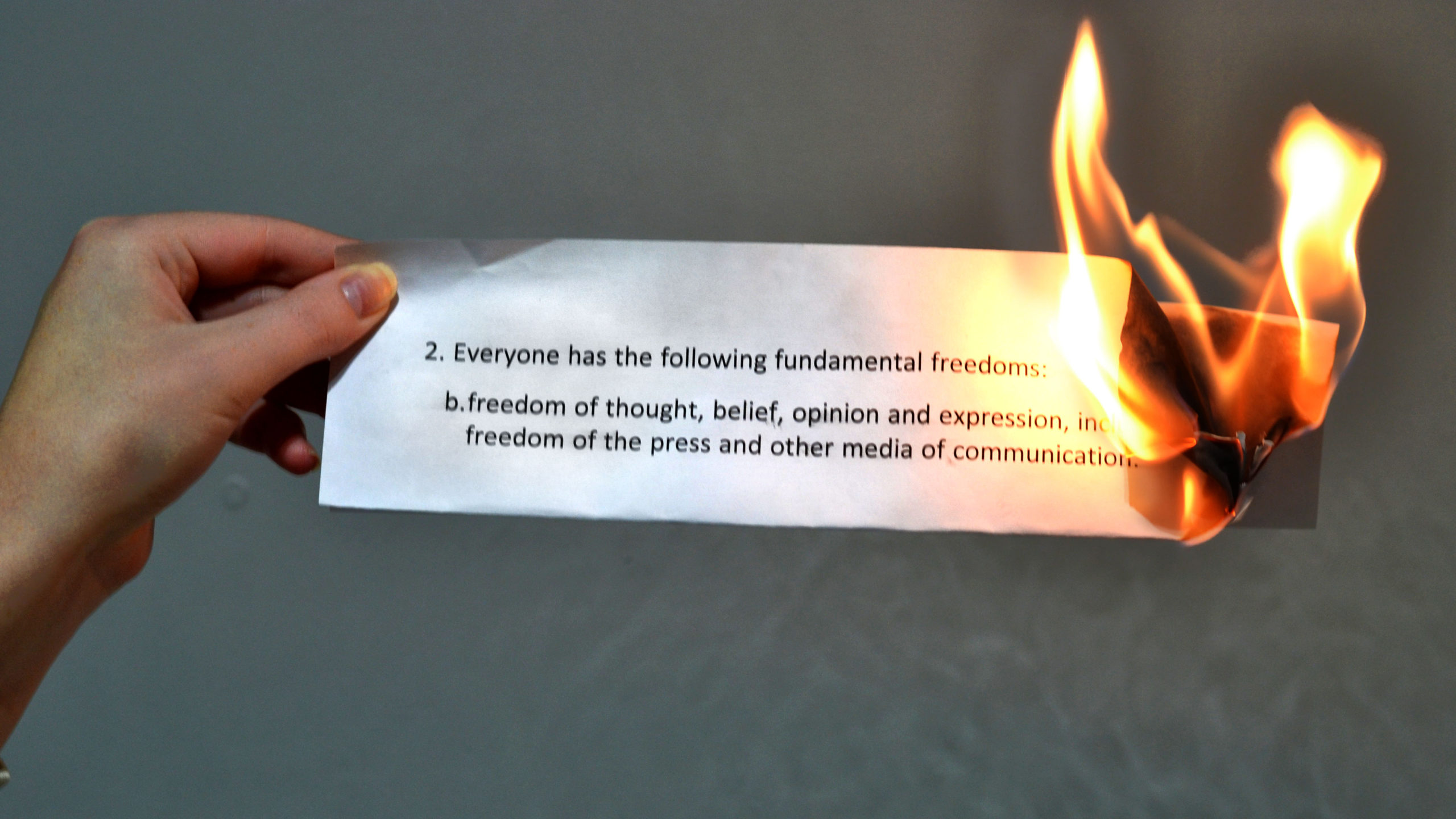

A person burns section two of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.It’s time to stand up for journalists’ right to cover and the public’s right to know

It was Colin Smith’s first time being arrested. His crime? Taking photos.

The Victoria Buzz photojournalist was standing on top of a concrete barrier, documenting the RCMP’s actions in the Fairy Creek watershed, when Staff Sgt. Jason Charney told him to move. A group of land defenders had linked arms across the logging road and the police were breaking them apart. This was supposed to be his story, not what was to come.

He told the officer he was a journalist.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said.

“Yes, it does,” Smith replied.

Charney grabbed his arm and told him he was under arrest.

Officers confiscated Smith’s camera gear, put him in a police van and drove him away from the scene. He was eventually released without charges on the condition he leave the site for the day.

A month before this, a coalition of independent media outlets and press freedom groups had taken the RCMP to the B.C. Supreme Court. They wanted a media access clause added to forestry company Teal-Jones’s court-ordered injunction, following months of restrictions on journalists covering the old-growth logging protests on Vancouver Island.

The restrictions, as they stood, included media pens, sometimes more than 100 metres away from the action, and required journalists to be escorted by police at all times. They often had to wait for hours at the police checkpoint for a liaison officer. Previously, the RCMP enforced a broad exclusion zone, denying reporters access to the site altogether.

The coalition’s application was granted by Justice Douglas Thompson on July 20, 2021. On Aug. 9, he published his written decision, stating that the media access clause would remind the RCMP to “take account of the media’s special role in a free and democratic society.”

Smith was arrested on Aug. 10; one day after the B.C. Supreme Court affirmed the photojournalist’s right to cover the protest.

Smith was not the first journalist to be arrested on the job, and he wouldn’t be the last. On Nov. 19, 2021, two journalists were arrested and put in jail while covering police actions in Wet’suwet’en territory in northern British Columbia. They were held in custody for three days.

When police arrest journalists for covering events, they are acting outside of the law. Freedom of the press is protected under section 2(b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and has been upheld by the courts as a crucial part of a democratic society.

Why then, are there still journalists prevented from doing their jobs?

When coverage is criminalized

In 2021, reporting was impeded by the RCMP at the Fairy Creek blockades and in Wet’suwet’en territory, and by the Toronto Police during homeless encampment clearings in the city’s parks. Media access was also restricted by the Halifax Regional Police when city staff removed crisis shelters on public land that were built by the anonymous group Halifax Mutual Aid.

In 2020, coverage was controlled when the RCMP raided the camps blocking the Coastal GasLink pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory, and when the Ontario Provincial Police raided Six Nations members’ occupation of a housing development site, dubbed 1492 Land Back Lane, in Caledonia, Ont.

There is no official data on press freedom violations in Canada, but news media have reported on the arrests or detainments of 12 journalists in the past two years. Many more have been threatened with arrest while attempting to cover police enforcements.

According to Lisa Taylor, an associate professor at Ryerson’s School of Journalism, these press freedom infringements are a trend, and a concerning one. “It’s a really troubling signpost in terms of where we are in our democracy,” she says.

Fairy Creek, Wet’suwet’en and 1492 Land Back Lane were Indigenous-led demonstrations where court injunctions had been granted to remove protesters. Journalists were arrested at all three, despite a 2019 ruling by the highest court in Newfoundland and Labrador, which gave protection to journalists covering protests, even when an injunction is in place.

In that case in 2016, Justin Brake faced both criminal and civil charges after entering the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project site in Labrador to cover an Indigenous-led occupation. Justice Derek Green later dismissed Brake’s civil charges. He said in a written ruling that the media has an important role to play in reconciliation, which places “heightened importance” on journalists’ ability to cover Indigenous land protests.

Green’s decision was celebrated as a victory for press freedom in Canada. The court made clear journalists’ right and duty to cover protests. Nevertheless, law enforcement bodies continue to obstruct journalists covering state actions across the country.

No witnesses

On June 22, 2021, photojournalist Ian Willms was documenting the Toronto Police’s clearing of a homeless encampment in Trinity Bellwoods Park. The officers had surrounded a cluster of tents in a fenced off area, about 100 metres away from Willms. He wanted a closer look. Willms asked officers if he could bypass the fence, stating he was a journalist. They turned their backs on him, so he climbed the fence. Willms was immediately arrested.

The freelancer says police fear accountability, which is why they want to control what journalists see. Willms believes it’s essential for there to be witnesses when law enforcement is dealing with vulnerable populations, such as people experiencing homelessness

“When the police prevent journalists from getting access … that prevents the public from fully understanding the scope of what’s occurring,” he says. “They should want to know where their tax dollars are going … what kinds of things are occurring in their communities on their dime.”

Weeks after Justice Thompson’s ruling in British Columbia, Ricochet Media reporter Clay Nikiforuk was forced to stay in a small, taped-off area where they could “barely see or hear” the land defenders at Fairy Creek, including young people who had locked themselves in trenches (called “hard locks”) to block the road.

“What really sticks with me is how many youth I encountered … and how vulnerable they are,” Nikiforuk says. “Somebody needs to witness what happens to them.”

Officers stood by media to make sure they didn’t move. “We’re kind of being treated like criminals,” Nikiforuk says, “like we’re almost under arrest as well.”

The police told journalists the restrictions were for their safety. “I made a joke with the liaison [officer], being like, ‘oh yeah, if one of the poles falls over and then shoots forward by 50 feet, we’d be screwed,’” Nikiforuk says.

He laughed and walked away. “He knew he was full of shit.”

The tipping point

Alexa MacLean recalls Aug. 18, 2021, as the day Halifax lost its innocence. Documenting the clashes between citizens and police during the evictions of people living in Halifax Mutual Aid shelters, she realized what happens in “other, bigger cities” can happen in Halifax too.

The Global News reporter was one of the journalists threatened with arrest that day. She posted a video to Twitter showing two officers walking her colleague, CTV reporter Sarah Plowman, back to the stairwell where journalists had been told to stay. The video garnered national attention.

MacLean says people are becoming increasingly aware of restrictions being placed on journalists, and the reactions to her video “reiterated to me the reasons why it is crucial that we uphold the rights of the press.”

She says we’re at a “tipping point” for social issues like the housing crisis and expects to see more instances of citizen uprisings where police get involved. “We will be there as journalists,” she says. “I ask that everyone do their jobs respectfully.”

The bright side

As the president of the Canadian Association of Journalists, Brent Jolly has been sounding the alarm on press freedom infringements for a year and a half.

Even though police are “continually trying to take control” of reporting, Jolly sees a reason to remain optimistic: people are finally paying attention, especially when it comes to how police behave.

“While people certainly don’t love journalists all the time, I do think that the idea of police going outside the bounds of the law is something that resonates with people,” he says.

Jolly says major news organizations, who were previously concerned about journalists involving themselves in stories, have realized this is “mission critical” and want to get involved.

“There shouldn’t be any neutrality around media rights, because if you don’t stand up and fight for them, they’re gonna go away.”

Moving forward

The public has its eyes on the issue, and newsrooms are ready to push for change. What’s next?

Before the end of the year, J-Source will launch the Canada Press Freedom Project, an online research hub and database that will document press freedom violations nationwide.

Lisa Taylor urges journalists to tell their stories to researchers, because the reports will “land on the desks of lawmakers.”

Jolly adds that police have recently provided “some really good examples” of why the law needs to evolve to better uphold freedom of expression.

Jolly is also pushing for a “mutual education campaign,” a dialogue between law enforcement and journalists to foster better understanding of each other’s rights in a protest environment. The CAJ has reached out to the RCMP and Toronto Police, but Jolly says there was a “lack of interest.”

The Toronto Police held its own meeting with news outlets following the arrests at the park encampment clearings, according to an email from their director of corporate communications.

In situations like Fairy Creek, where there’s a police checkpoint, Colin Smith says journalists should be given an identifier, like an orange wristband, so officers don’t mistake them for protesters. The photojournalist always wore a Victoria Buzz badge, but that didn’t prevent him from being arrested.

He returned to work at Fairy Creek after his arrest.

“Oh, he came back,” an officer joked.

“I just kind of looked at him and said, ‘of course I did.’”

About the author

Kaija Jussinoja

...