33 years after Ecole Polytechnique shooting, Dal engineering students ‘dare to take up space’

Women in field spotlight continued gender disparity in universities and the workplace

caption

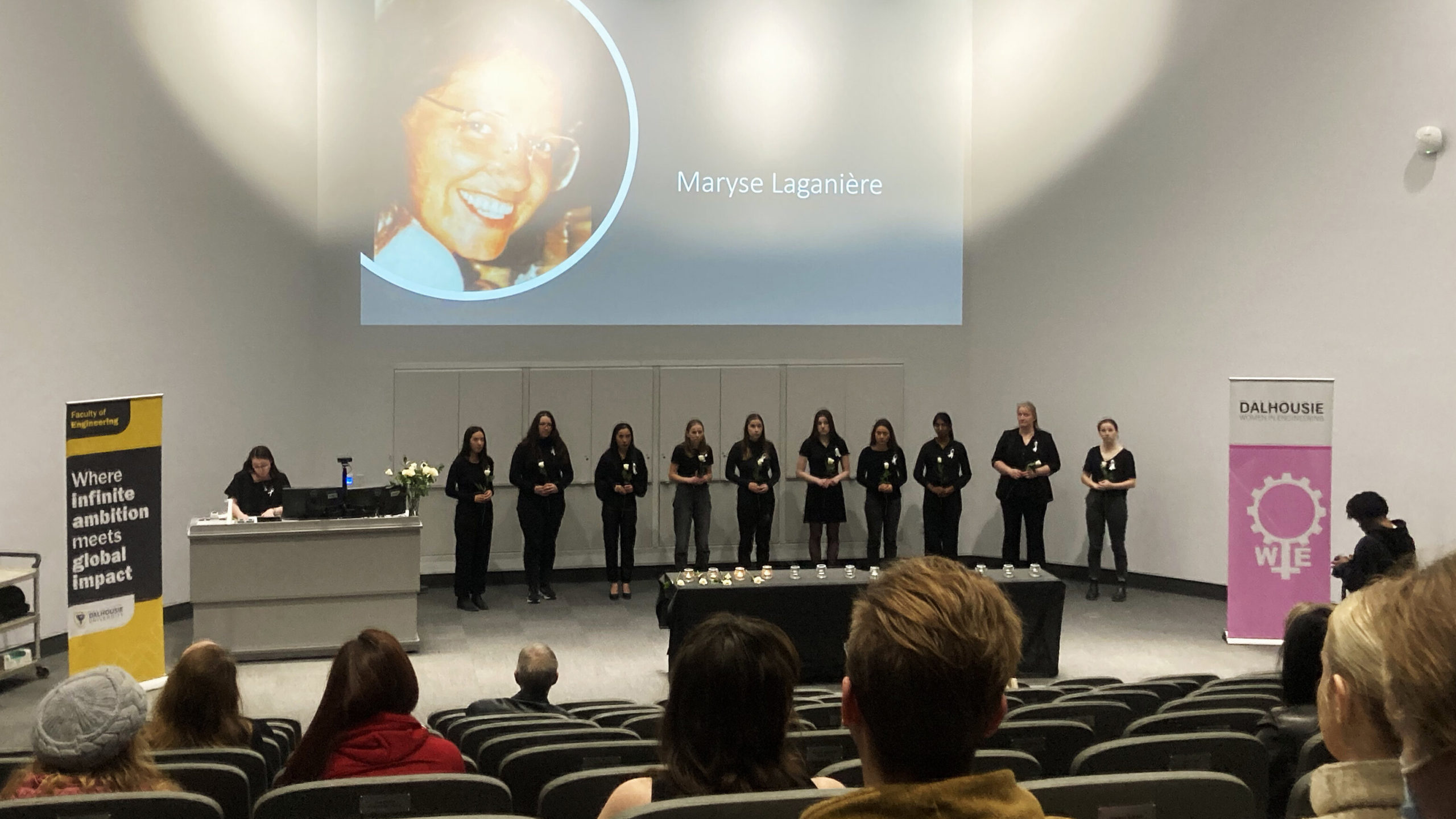

The Dalhousie Women in Engineering Society (DALWIE) hosted their annual remembrance and resilience ceremony for victims of the 1989 Ecole Polytechnique Massacre at Dalhousie’s Richard Murray Design Building Tuesday evening.Sapna Natarajan was proud to represent women in engineering at Tuesday evening’s remembrance ceremony for victims of the Ecole Polytechnique Shooting.

“Just like the 14 women who were killed 33 years ago today, I, too, proudly dare to take up space,” she said to a room of around 50 people seated in the Irving Oil Auditorium on the Dalhousie University campus.

“Today symbolizes determination and perseverance for all women.”

Natarajan is a third-year chemical engineering student at Dalhousie. She’s also the VP outreach of The Dalhousie Women in Engineering Society (DALWIE). According to its president, Teo Milos, the society has hosted the ceremony annually for around 10 years.

caption

14 candles were lit and put out during Tuesday’s ceremony to represent the lives lost during the 1989 Ecole Polytechnique shooting.Dec. 6 marks The National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women in Canada, which was sparked by a massacre of 14 women in Montreal in 1989. 12 of them were engineering students.

caption

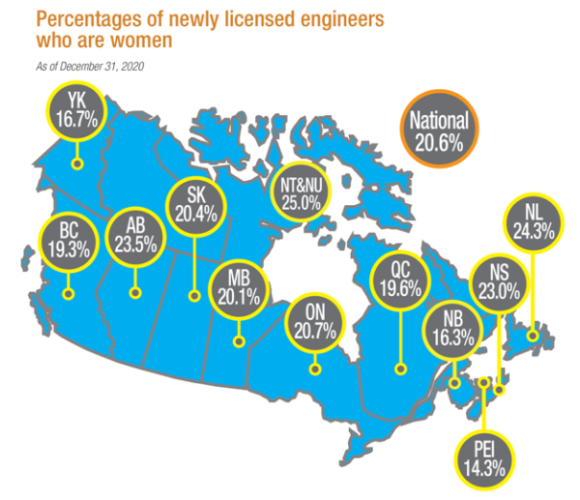

Source: Engineers CanadaWomen made up 23 per cent of all engineers in Nova Scotia in 2020, according to Engineers Canada, an organization that oversees the engineering profession. Engineers Canada’s 30 by 30 goal sets out to ensure that 30 per cent of licensed professional engineers are women by 2030.

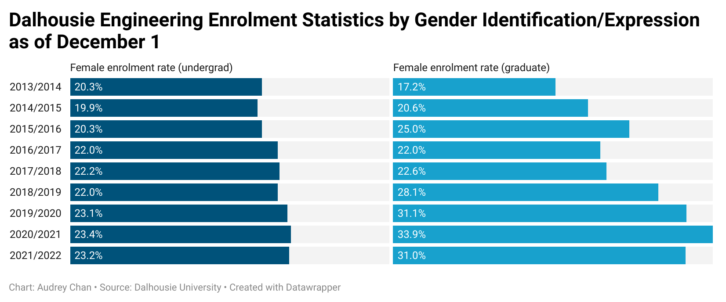

Dalhousie’s enrolment statistics show that the proportion of female-identifying engineering undergraduate students increased 2.9 percentage points over the last nine years. That took enrolment from 20.3 per cent to 23.2 per cent between 2013 to 2022, compared to male-identifying students. The enrolment of female-identifying graduate students, on the other hand, jumped 13.8 percentage points in comparison to male-identifying students within those years.

caption

Audrey ChanAparna Mohan, a Dalhousie engineering student who took part in Tuesday’s ceremony, doesn’t think the 30 per cent target will be reached in time. She said gendered learning environments continue to deter women from entering the field.

“Women students often end up taking on or being delegated record-writing and less of the practical components of the work. And it’s very subtle, because it’s framed as, ‘Oh, this is something that you’re good at,’ but it can be condescending and it can limit the exposure and the professional development of our students,” she said.

“We also see that gender-based discrimination come up a lot for our students in co-op placements,” she added. “One of the biggest reasons for the lack of retention of women in engineering actually is the workplace itself. And this can be a big deterrent for women to stay in engineering because they find they’re consistently underestimated and undermined.”

John Newhook, Dalhousie University’s dean of engineering, recognizes that the field is historically male-dominated. He thinks it’s important that young women in engineering have role models to look up to for that reason.

“Every young student who is interested in engineering should have the opportunity to pursue that goal, and equally importantly, feel completely included and respected in that community,” he told The Signal in an email.

Newhook said Dalhousie’s engineering faculty is working to remove barriers that are stunting the percentage of women in programs and the workforce. The faculty is promoting mentorship opportunities for students with women alumni and members of the profession and are increasing scholarships for female-identifying students.

Amanda MacLean is a recent engineering graduate from Dalhousie who spoke at the ceremony. In an interview, she said the shooting sunk in for her when she got into her program and started drawing parallels between herself and the women who died in the shooting.

“There’s this idea of always feeling the need to be the most competent person in any situation for fear that, you know, being a woman in the field might affect someone’s judgment of you,” she said.

Mohan said she wants the fight for gender parity in engineering to account for other systemic barriers that prevent women from staying in the field, namely race. She recalled being told by other women that she was too direct for a woman in a workplace.

“The work on gender-based discrimination and violence is in desperate need of a more intersectional lens in engineering,” she said. “Often, the gender-based discrimination that women face is from other more racially-privileged women.”

That said, Mohan sees the impact outreach programs have on young women.

“There is this event called Go Eng Girl, which deals with recruitment and outreach for high school aged women. So that inspires more of them to get into engineering,” she said. “We’ve had many students apply that were part of Go Eng Girl when they were in high school.”

About the author

Audrey Chan

Audrey (they/them) is a journalism student at the University of King's College. They have a background in Contemporary Studies and Cinema &...