Health

6 things Haligonians need to know about the Zika virus

caption

[media-credit id=101077 align=”aligncenter” width=”726″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Headlines about the Zika virus continue to cause anxiety around the world. With all the information circulating, it can be difficult to assess the risk to Canadian travellers. As winter carries on, many are escaping to warmer areas, which may put them at risk.

Here’s a run-down of what you should know.

1. What is it?

The Zika virus is carried through the Aedes aegypti mosquito. The virus is linked to microcephaly. It causes unusually small heads and damaged brains in newborn babies, although scientists do not fully understand the connection. There is currently no vaccine to prevent Zika or medicine to treat infection.

The World Health Organization has declared Zika-linked microcephaly a global health emergency, but there is no definitive evidence that the virus is the cause.

On February 24, it was announced that Zika may be transmitted from a male to a female during intercourse, as there are 14 possible sexually transmitted cases. There is no research or evidence surrounding women transmitting the virus.

2. Where is it?

Zika virus is not new. It has been reported in Africa and parts of Asia since the 1950s, and in the southwestern Pacific Ocean in 2007.

In 2015, the virus emerged in South America with widespread outbreaks reported in Brazil and Colombia.

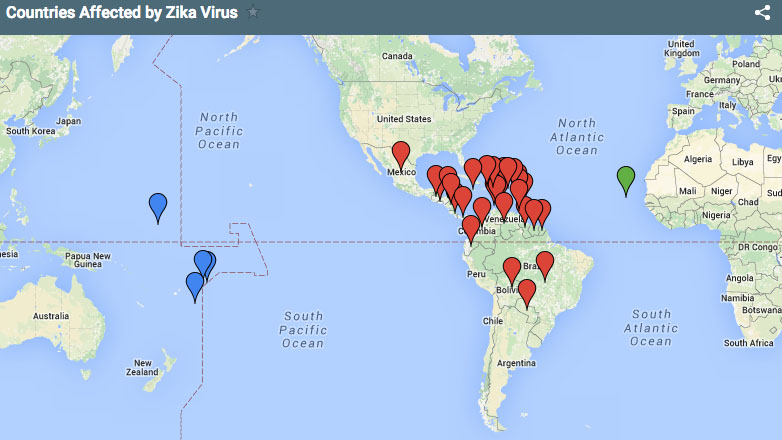

The areas where Zika is present are shown on the map below.

According to the WHO, the worst-hit country is Brazil due to its high spike in babies being born with microcephaly. As of January 29 there were five confirmed cases of Zika virus in Canada from travellers returning from affected areas: two in British Columbia, one in Alberta, one in Quebec, and a recently confirmed case in Ontario.

To date there have been no cases of Zika contracted from within Canada.

3. Who is at risk?

Based on the Public Health Agency of Canada’s current information, the risk to Canadians in Canada is extremely low, as the mosquitoes known to transmit the virus are not suited to our climate.

The most at-risk group is pregnant women, women planning on becoming pregnant, and women who could become pregnant. If you are in this group, it is recommended to avoid or postpone travelling to affected areas.

If this doesn’t apply to you, many doctors say there is little concern for travel. If a traveller contracts the virus, there is no guarantee they will become sick or even develop symptoms.

Travel agents, such as Pamela Genaille of Sears Travel are giving similar advice to concerned customers.

“We find that most clients actually aren’t too concerned about the Zika virus when travelling,” she says. “If clients do not fall into these categories (being pregnant) we just tell them the most common symptoms.”

4. What to do before going and while you’re there

At-risk travellers who cannot cancel or postpone their trips are advised to take precautions, such as using insect repellent and covering up exposed skin during the day. It is also advised to re-apply insect repellent after being in the water. Genaille also suggests staying away from standing water.

Pregnant women are advised to speak with their doctors before travel regarding risk and protection. The federal government has more information on mosquito-bite prevention online.

“There’s a lot that we still don’t know about this virus, so if you have any questions or worries, the best thing is to call your doctor,” says Helen O’Donnell, a registered nurse in Alberta.

5. How to know when you’ve been infected

Fever, rash, joint pain and red eyes are the most common symptoms, according to the Center for Disease Control. Symptoms usually last two to seven days, and will go away on their own.

“Plenty of rest, drink fluids to prevent dehydration, and take Tylenol, not Advil,” suggests O’Donnell.

However, an estimated 80 per cent of people who have the virus have no symptoms, making it difficult for pregnant women to know whether they have been infected. Cases requiring hospitalization are very uncommon. There is currently no specific treatment or cure for the virus.

If you are unsure about your symptoms, see a doctor.

6. What to know when you return

The Public Health Agency of Canada advises women to wait at least two months after returning from an affected area to start conceiving, and to see your physician immediately after returning.

Men returning from affected areas are advised to wear condoms during intercourse for at least two months, and if they have a pregnant partner, should wear condoms during the duration of the pregnancy.

Canadian Blood Services says anyone who has travelled outside of Canada, the continental United States and Europe will now be temporarily ineligible to give blood for three weeks. This is to ensure that the virus has enough time to be eliminated from the bloodstream.

Genaille advises many of her clients not to worry too much.

“Since the outbreak we have only had one booking cancel their vacation due to pregnancy,” she says. “A lot of this seems to have been blown a little bit out of proportion.”