WEATHER

Amateur weather forecaster hooked on Mother Nature’s power

Thousands of Maritimers turn to Tykian Llwellyn for their forecasts

caption

Storms aren't uncommon in a Nova Scotian spring.

caption

Storms aren’t uncommon in a Nova Scotian spring.The storm nicknamed White Juan hit the Maritimes in February 2004. It blanketed Nova Scotia with about a metre of snow, breaking records across the province.

Tykian Llwellyn remembers it vividly. He was hooked from the first flakes.

“It just didn’t let up. I just sat there and stared all evening into the snow, just watched it.”

When he emerged that Monday after spending a few days snowed-in at his home in Kentville, N.S., he was amazed by what he saw.

Snowbanks towered along the cleared walkway — like lockers in a school hallway.

“There was nothing we could do. All the creations we have and all the technology, and there we were, stopped in our tracks. By water. How cool is that?”

A spare-time storm tracker

Now Llwellyn channels his awe into updating his amateur forecast page, Maritime Storm Trackers. He spends about 20 minutes a day –– more during storms –– checking weather models from the National Hurricane Center and Meteocentre to predict the amount of snow or rain headed this way.

Llwellyn isn’t trained in meteorology, though he says he would like to be someday. He turned to interpreting weather models after being disappointed by “false” forecasts. He contributed to another amateur forecasting page, Maritime Weather Agency, before creating his own Facebook page in February 2014.

His system is a makeshift one, developed over time by watching the models and comparing it to what happened outside his own window.

It seems to be working for his readers. At the beginning of this year, the Maritime Storm Trackers Facebook page had just over 3,000 likes. Now, it’s up to over 8,200.

caption

Ian Folkins shows a swirling storm on a weather model.More than just book learning

Ian Folkins is the co-ordinator of Dalhousie’s meteorology diploma program and a professor of atmospheric science. He says just because amateur forecasters aren’t necessarily trained doesn’t mean they can’t still make accurate predictions.

“Academic training gives you a certain insight into weather, but a large part of the weather is just developing intuition over time.”

Students in the meteorology program take classes in atmospheric physics and chemistry, physical oceanography, and light scattering, to name a few subjects.

Folkins says amateur forecasters won’t have an understanding of the physics of weather patterns the way someone who’s studied them does.

But the greatest difference between a professional agency and an amateur are restrictions on how early they can make calls.

In addition to releasing models like the ones Llwellyn uses, Environment Canada puts out forecasts.

“They have to work within institutional confines,” says Folkins. “There’s regulations about how early they can give storm warnings, about what their criteria for storm warnings are going to be.”

Llwellyn, as an amateur, doesn’t have any restrictions. Still, he holds himself to a high standard.

“There were a couple of storms just recently where people were like ‘oh no, you were spot on, you were spot on.’ I was spot on some places. For those people in their area, I was spot on. But there were some areas that I was over 15 centimetres short. That’s not spot on to me.”

Bob Robichaud, a meteorologist with Environment Canada, says they don’t track actual amounts of precipitation against their predictions after the fact, so there’s no detailed record of how accurate their forecasts are.

As long as readers are aware of the room for error, Folkins thinks it’s fine for amateurs like Llwellyn to publish what they see on the models.

“There’s no problem with people talking about it and filling this vacuum of interest out there.”

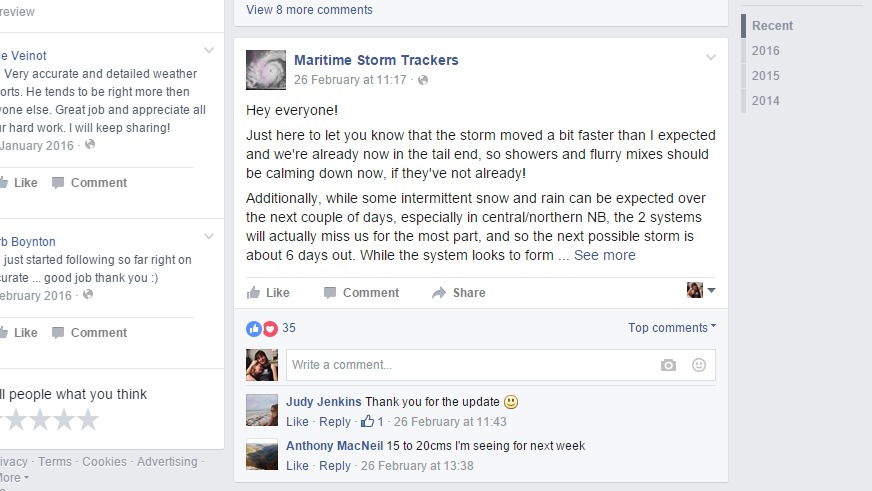

caption

Comments on the Maritime Storm Trackers Facebook page.Interactive appeal

Llwellyn’s readers are generally supportive. Barbi MacDonald is one of them. She lives in Mount Uniacke, north of Halifax, but drives into the city a few times a week to visit her 94-year-old mother. In the summer, she can just hop in the car and go. But in the winter storm season, she plans her week around the weather.

“I tend to go onto Facebook, key him in, read what he’s got to say and go with that,” she says.

It’s not like Llwellyn’s page is her only option. Weather is important enough to people’s daily lives that there are forecasts available 24 hours a day both online and on television.

MacDonald says she turns to Llwellyn for his personal, localized predictions. When she happens to catch a Weather Network broadcast, she says she sees the same things rehashed throughout the day.

“I find a lot of the time, I hate to say it, but they do a really good weather forecast right across Canada and they stop at the Quebec border, it’s like we hardly even matter.”

MacDonald also appreciates Llwellyn’s interaction with his readers. She is one of many who will sign on to comment a “thank you,” or let the other readers know what the weather’s like near her.

Lllwellyn says he’s now spending more time chatting with his followers than reading the models. This isn’t a job for him –– he’s not receiving any pay for his posts. He spends the time because it’s important to him to make the forecast accessible to his readers, and that friendly environment is key.

“No question is stupid. Only answers can be stupid. If you don’t know something, ask. I want people to feel like they can ask.”

D

Doug Barron