Wildlife

Patrick Farmer’s friendly flock of crows

Over 10 years, trust has grown between a man and birds

caption

caption

The crow with the hooked beak sits near Farmer’s back door.The wild crow with the hooked beak didn’t always trust Patrick Farmer.

It took years for the bird to overcome its innate fear of humans and eat out of Farmer’s hand. Now the bird comes by his house almost every day.

“I think it’s really cool that one would come close enough to me to take the peanut,” he says.

Farmer’s relationship with a local flock of crows began 10 years ago, when his dog Gracie didn’t finish her food on the family’s back porch in Dartmouth. The flock noticed the extra food and before long, “they were here every day,” says Farmer.

At first, the birds would keep their distance, only eating what was thrown their way. But slowly they crept closer, with the hooked beak crow being the bravest of all: it began to sit on the railing of Farmer’s back porch, within an arm’s reach of him.

With a level of trust solidified, Farmer started to reach toward the bird, peanut in hand, until it trusted him enough to grab it out of his palm.

Now that crow, whose hook recently broke off, can often be found on the railing. It can catch peanuts in its mouth, as shown in the video above shot by Farmer. And it doesn’t flinch at the comings and goings of Farmer, his wife or his daughters who all walk within a foot of it.

Crows are wild animals, but these crows seem to be verging on pet behaviour. To Farmer’s family and others, urban wildlife offers amusement. But bringing crows closer to human lives may risk harming them.

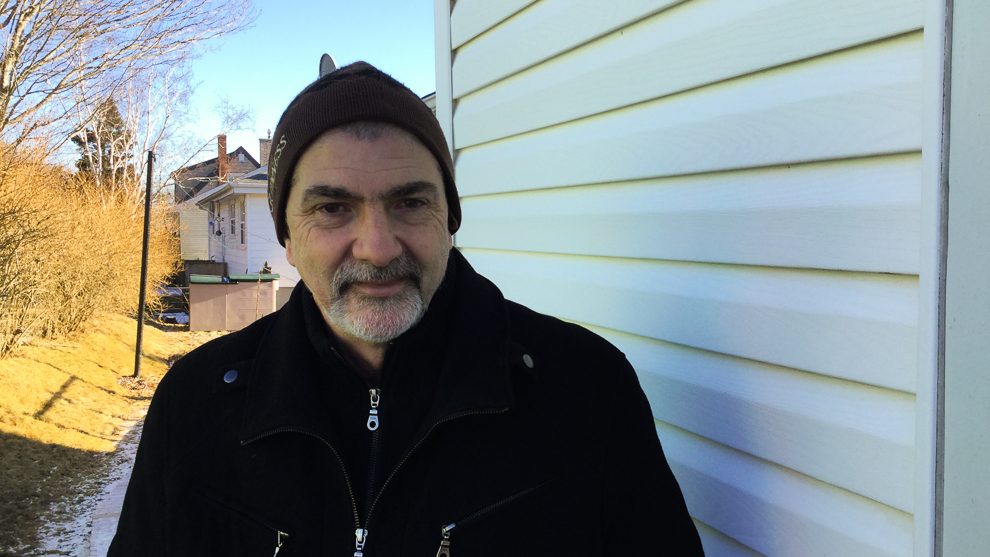

caption

Farmer stands on his back porch, which is where he feeds the crows.Andy Horn, an ornithologist at Dalhousie University, says that the friendly behaviour of this particular flock is consistent with previous studies on crows.

Horn says crows are very social, intelligent animals.

“(Some researchers) are thinking more and more that they’re kind of on par with many of the primates,” says Horn, adding that their vast social networks are an indicator of this intelligence.

Crow chicks are raised not only by two parents, but often by aunts, uncles and older siblings as well.

Horn says it’s possible that people may be part of a crow’s social network, but this isn’t confirmed.

“It’s tough to know how crows perceive us,” he says. Whether they view people like Farmer as a companion or a mere food source is hard to tell.

caption

Some other members of the flock that visits Farmer’s house.Over the last decade, Farmer has seen the flock change. Some years, blue-eyed chicks have appeared, then grown. Other crows have died. The average lifespan of American Crows that reach adulthood is six to 10 years; although there have been reports of some crows living up to 29 years.

But as the flock’s makeup changes, its behaviour stays the same. From their perch on a high-roofed church a few hundred metres away, the crows keep sharp eyes on Farmer’s back door. When they see him exit, they swoop down hoping for a snack.

Farmer says he makes sure that they don’t become reliant on these snacks.

“I don’t feed them enough that they don’t want to go forage for their own food,” he says.

Hope Swinimer, founder and president of wildlife rehabilitation and education centre Hope for Wildlife, says it’s important animals don’t become reliant on humans.

“When you feed (animals) it creates a whole lot of problems you don’t even think about,” she says.

Although it can be nice to play Snow White, routine feeding can pose a grave threat to animals in the long-run. For instance, Swinimer says animals that rely on specific people for food sometimes die when those people go on vacation. Others who are fed lose their natural fear of humans, which can put them in dangerous situations.

On the other hand, “getting people reacquainted with the natural world is never a bad thing,” says Swinimer.

Farmer isn’t the only one to have a relationship with crows. Dozens of people answered a post in the Nova Scotia Bird Society Facebook group about crow companions. Here are just a few of some of the comments: