When the news breaks the journalist

caption

Graphic by Danielle McCreadieJournalists are coming out and talking honestly about mental illness

On a chilly November morning in 2001, reporter Andrea Petersen was on an assignment for the Wall Street Journal. She was sitting in her car surveying a New Jersey post office when suddenly she couldn’t breathe.

Petersen was investigating a series of post 9-11 anthrax attacks on media outlets and politicians. After a week of working long hours and eating little, she had a panic attack. Heart pounding and vision blurred, she managed to drive herself to a nearby hospital and ask for help.

She was clinically diagnosed with anxiety, which manifests in a couple of ways: phobias (particularly a concern for health), and panic attacks. Knowing the name of the problem helped her know how to deal with it.

In the dark

When it comes to mental illness, journalists are suffering more than they let on. While post-traumatic stress disorder among reporters has garnered deserved attention in the past few years, journalists like Petersen, who struggle with anxiety and depression, have largely been left in the dark.

A 2013 study by the International Journal of Social Psychiatry, a SAGE publication, reviewed the mental health of journalists and found that the prevalence of anxiety disorders is higher than the general population. Journalists tend to recognize that mental health is important, and needs to be seriously discussed. But the study reveals there are workplace disincentives to disclosing a mental health issue.

The standard newsroom script calls for stoicism, and objective observation. Journalists are aware that if they show vulnerability, some editors may be hesitant to assign them to certain stories.

When Petersen had her panic attack, she knew what not to do. “I did not tell my editor.” She was afraid of being judged, and seen as less capable. No one in her newsroom knew that she suffered from a mental illness until she published her 2017 book On Edge.

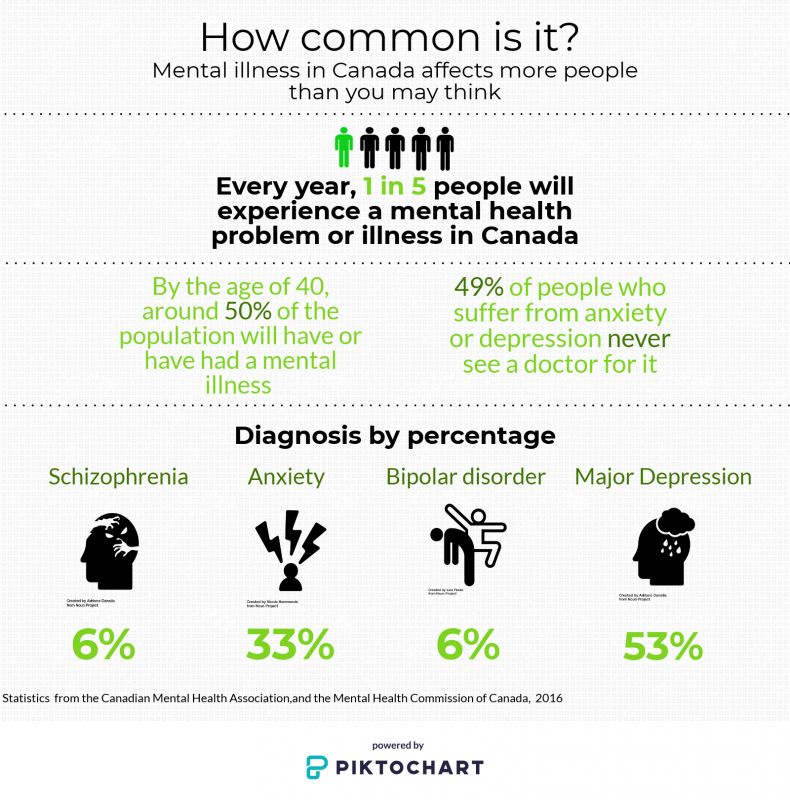

According to the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), a leading teaching hospital and research centre in Toronto, one in five Canadians will struggle with a mental health issue in their lifetime. Anxiety is the most prevalent, affecting 25 per cent of Canadians.

caption

Danielle McCreadieSome anxiety is good for us—it’s what motivates us to study for tests, speak in front of crowds, and achieve our goals. But when fear and worry are excessive they can become debilitating, leading to panic attacks or avoidance tactics.

“The fear of not getting a story, or getting beaten to a story, is something journalists, whether they suffer from clinical anxiety or not, can relate to,” says Petersen.

That fear can drive journalists to work harder. When she first started out at the WSJ, the fear of looming catastrophe, a symptom of her anxiety, was actually helpful. “It drove me to triple-check that spelling, make one more phone call. It made me more tenacious.”

But when Petersen was in N.J. that morning in November, she was consumed by panic. It was the only time in her career she was unable to finish a story, and she sees it as a low point in her career.

“Anxiety is exhausting,” she sighs.

Most days Petersen’s anxiety doesn’t bother her, but she’s learned to be diligent. When she feels panic rising at work, she texts a close friend in the newsroom, and they go for a walk. Having a support system like this has been her saving grace when under pressure.

Establishing an education

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma is a project of Columbia University’s Journalism School. Its team of journalists, journalism educators, and health professionals are dedicated to improving the way journalists talk about mental health. Clinical psychologist Dr. Elana Newman, the Dart Center’s research director, has worked there for 21 years. She sees herself as “an advocate for journalists” who wants to “help good journalists continue to do important work.”

Almost every journalist will cover a traumatic event in their career. Research posted by the Dart Center shows that at least 80 per cent of journalists around the world have been exposed to trauma: this can range from covering a car crash to reporting from a conflict zone. Newman notes that while soldiers and police officers are typically offered counselling after such events, journalists are merely assigned another story.

While Newman has mainly studied PTSD in journalists, she believes more focus needs to be put on the daily beat reporters. “It’s an issue across the board,” she says. “That’s where the discussion needs to happen more.”

The Dart Center urges newsrooms to pay attention to the warning signs that someone may be struggling during a difficult story. Symptoms include unusual irritability and increasing isolation.

Suffering in silence

In 2015 Gabriel Arana, a freelancer who contributes to the American Prospect and Salon, wrote a five-part series on mental health in the newsroom for HuffPost. His mental health advocacy stems from a deeply personal experience: In 2012, he wrote a story that re-traumatized him in ways he didn’t expect.

As an openly gay man, Arana wrote about going through conversion therapy as a teenager. He didn’t think the story would affect him, but as he delved back into his past he was haunted by terrible memories. His mental health suffered, and no one asked if he was okay.

“I would drink a lot, and no one ever knew I was struggling except for my husband.”

And he’s not alone. In 2014, broadcast journalist Mark Joyella had enough of staying silent. He decided to “come out” about his mental illness, and told his story publicly.

For the past 25 years he’s worked in TV newsrooms from stretching from Orlando to New York City. He now writes for IBM. For years, he kept his mental illness a secret from friends, family and colleagues. “There’s a great deal of fear that if you do talk about it, it could damage your career,” he says.

For most of his career as a journalist, Joyella’s illness went untreated. He didn’t handle the pressure well at times, and often coped through self-medication.

“The thing that inspires me the most when I revealed my illness was that I heard from all kinds of people – including people I knew and had worked with – who said ‘yeah, me too’.”

Created using Visme. The Easy Visual Communication Tool.

Changes from the inside out

Newman of the Dart Center urges the industry to explore ways to promote resiliency. “I’m not talking about changing the world, but about very simple things,” she says. “Like validating good work, providing social support and networks, acknowledging when things are difficult, giving people opportunities to rotate sometimes. There are lots of little strategies like that.”

Mental health tactics for journalists can and should be taught early on, while they are in school, Newman says. According to CAMH statistics, in Canada young people ages 15 to 24 are more likely to experience mental illness than any other age group. This is a crisis on Canadian campuses, and demand on university mental health services is increasing at an alarming rate. Opening a dialogue where student journalists can feel comfortable talking about their emotions is a crucial step.

That’s exactly what Ann Rauhala at Ryerson University is dedicated to doing. She’s an instructor in the School of Journalism, and is adamant that the power to change the “macho culture” of newsrooms relies in the education of the next generation.

“I was tired of seeing students suffering from stress and anxiety, and I wanted to find a way to be more helpful to them instead of shrugging my shoulders,” Rauhala says. “It’s true, I’m not a trained psychologist, but I am a human being.”

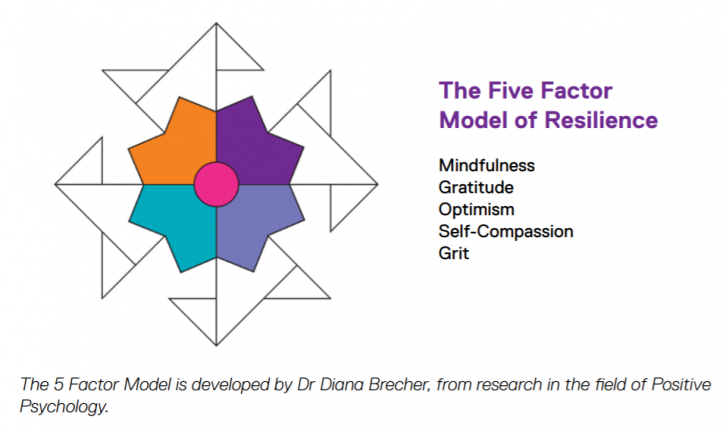

In March 2016, Ryerson journalism faculty members held a teach-in to discuss the issues young journalists face. They brought in clinical psychiatrist Dr. Diana Brecher, Ryerson’s scholar in residence, to talk about building resiliency. Brecher, who has worked for 26 years in Ryerson’s counselling centre, developed a five-step model aimed at building resiliency. Rauhala says her students can learn a lot from this.

caption

One skill Brecher highlights is mindfulness, the practice of being in the present moment. Mindfulness has shown to increase mental stamina and decrease stress. It’s not a cure for a mental illness, but a coping skill that has a multitude of benefits.

“It’s a great way to deal with procrastination,” says Rauhala. “It increases my focus, it improves my mood… I feel less flustered by obstacles and enjoy successes more.” ‘

The school received internal funding to run a mini-course on mindfulness, modelled after a successful course at Duke University in North Carolina. Rauhala hopes it will help her students feel less anxious and stressed when working on stories. And she hopes to see it become a mandatory part of the curriculum.

Rauhala was moved when emails expressing support for the mental health initiative poured in from former students now working in important newsrooms across Canada. “‘This is fantastic’,” they said. “It’s about time.”