Industry

Not all fun and games

Nova Scotia has the highest digital media tax credit in Canada, but is it leaving some companies behind?

Nova Scotia has the highest digital media development tax credit for digital media development in the country, according to the Interactive Society of Nova Scotia, which is attracting more companies to the province.

Most of these companies are game development studios, with over 300 people employed and over 25 studios opening since the early 2000s, according to ISNS.

Ubisoft, known for popular video game franchises like Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry and Just Dance, opened an office in downtown Halifax In 2015 for mobile games. In the process it acquired Halifax-based Longtail Studios and added an additional 10 or more jobs.

Along with larger companies like Ubisoft, many smaller independently owned game companies have chosen to settle down in Nova Scotia, with teams ranging from two to 10 members. Independent studios are on the rise, with the Entertainment Software Association of Canada reporting over 228 opening across Canada as of 2017.

Fostering the video game industry can create high-paying jobs, with the average salary of a game developer in Canada being $77,300 per year, according to the ESAC.

However, the digital media tax credit costs millions of taxpayer dollars every year. This brings forth the question of how much of an impact the digital media industry has, since the credit was introduced, and if it’s only helping video game companies, instead of the entire digital media industry.

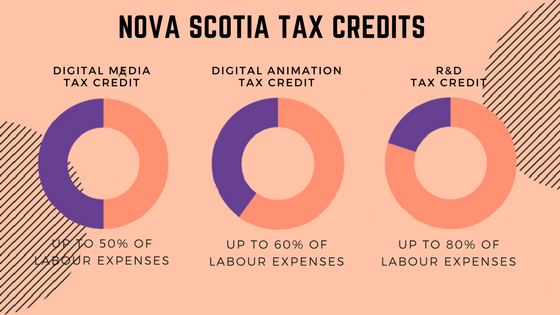

Breakdown of the tax credits

Nova Scotia offers a credit for up to 50 per cent of labour costs for digital media (or 25 per cent of the total project costs, whichever is lower), 60 per cent of labour for digital animation and 80 per cent of labour for research and development.

The digital media tax credit attempts to aid digital media companies by offering returns on certain expenditures in their taxes.

Expenditures that can be claimed include:

- 100 per cent of eligible Nova Scotia salaries.

- 65 per cent of third party labour payments.

There is also an additional credit available for interactive products, up to $100,000 to help pay marketing and distribution expenditures.

With credits like these, it appears both the federal and provincial government are focusing on increasing the digital media sector. According to the ESAC, while the wider Canadian economy grew by four per cent since 2015, the video game industry saw a 24 per cent increase.

ESAC CEO Jayson Hilchie once worked for Nova Scotia’s economic development agency, Nova Scotia Business Inc. He now oversees the representation of video game development companies in Canada, while also being a primary spokesperson for the industry itself.

When asked about digital media tax credits on a national scale, Hilchie says Canada is in good standing.

“I think Canada right now is by far the envy of the world when it comes to tax credits and government support and visibility,” says Hilchie.

In Nova Scotia, the tax credits were introduced because of Lunenburg-based studio HB Studios success. They’ve released titles such as The Golf Club and entries to the NFL, NHL, and other sports series.

HB Studios was founded in 2000 and now has over 80 employees at its Lunenburg location, while a Halifax-based studio opened in 2016 with six to 12 employees.

Working in a smaller area of Nova Scotia with no government support, HB Studios would find it harder to compete with other provinces, especially those with competitive tax credit incentives.

“(The government) created a tax incentive, in my experience and knowledge, mainly to ensure that HB Studios was going to stay in Nova Scotia, particularly Lunenburg,” says Hilchie. “It was created for one company and now there are over 20 video game companies in Nova Scotia, so it is a big success.”

View Nova Scotia Game Development Studios as a full screen map

To get a first-hand view of companies who are supplied this tax credit, we spoke to a few game studios currently working in Nova Scotia.

Game developer’s perspective

One of the newest studios to set up shop in Nova Scotia is Gogii Lighthouse Studios, currently located in Halifax. Having opened in 2017, it is the second studio to open for Gogii Games, after Moncton, N.B. in 2006.

The studio found success making games in which the user looks at the screen to find hidden objects, and since its opening have made over 30 titles for the PC and mobile platforms. The Halifax studio is tasked with porting and updating various games, including Fish Tycoon 2 and Virtual Villagers, to mobile platforms. Although it has yet to be announced, it was hinted the studio is also working on a game for the Nintendo Switch console.

While the Moncton studio currently has eight employees, the Halifax studio now has 12, a number that is expected to increase. Gogii has plans to move the Halifax studio from its waterfront location to a larger 30-person studio in the North End.

Darryl Wright, managing director for Gogii Lighthouse Studios, has been in the games industry for approximately 20 years. He has previously worked in B.C. at Electronic Arts and has his own game development company, Punk Science Studios.

caption

Gogii Lighthouse Games managing director Darryl Wright.After George Donovan, Gogii Games CEO, was introduced to Wright though NSBI in April 2017 he brought him into Gogii. At the time, they were looking to take take advantage of the digital media tax credits in Nova Scotia.

“There’s a lot of reasons to move to Halifax that are great and the digital media tax credit is a big one. George already thought it would be nice to have a Halifax studio, and there’s a lot of universities in the area that provide really top-level talent coming out of the CS courses,” says Wright. “But the icing on the cake is definitely the tax credits.”

As Wright states, local talent coming out of universities and colleges can be a big draw to potential game development studio heads, with NSCC, Dalhousie, Saint Mary’s, Eastern College, Acadia and daVinci College all offering game development programs.

Hilchie agrees local talent is crucial to the game industry’s success and growth in Nova Scotia, even more so than the tax credits.

“Ultimately the number one reason video game companies go to a particular jurisdiction is for the availability of talent. I think it’s people first and government support and interest second,” says Hilchie.

There are currently a lot of entry-level developers in the province and Wright believes finding and keeping more senior developers can be a challenge. Many developers start their careers in Nova Scotia, but once established might move to other provinces to work at bigger companies.

“It’s hard to hire good, experienced people; it’s still hard in Halifax,” says Wright. “A lot of time what happens is you bring someone in for three years and the next thing you know they move to Montreal or Vancouver.”

However, with the growing number of game studios in Halifax, this seems to be becoming less of a problem.

“I think it’s because there’s an ecosystem here, and if you had only one studio you would see that all the time, but now if somebody is unhappy with their job they can check out Hot Head or Ubisoft or Silverback and they are all sort of comparable studios where they might enjoy working,” says Wright.

caption

Gogii Lighthouse’s studio in downtown Halifax.Mobile game producer Adam Dionne previously worked in Halifax for Wright’s studio Punk Science, as well as the now defunct Orpheus Interactive. In 2016 he moved to Toronto and now works with major mobile game publisher Gameloft. With experience working in the game industry in both provinces, Dionne also notices a lack of senior developers in Nova Scotia.

“In Nova Scotia it’s a reasonably young industry, so as they try and build it up there’s not a lot of senior level or experienced game development people there to really build a community,” says Dionne. “I think there’s a stronger community in Toronto than there is in Nova Scotia, but I think that is a function of size and maturity of the industry.”

One tactic companies have used to try and keep senior developers is to attempt to enforce non-compete clauses, or NCCs, where an employee is told they are not allowed to work in the industry for a certain amount of time after leaving a company. They are usually not enforceable and are mainly used as a scare-tactic to pressure developers into staying with a company

Wright says eight to 10 years ago, an attempt to issue NCC’s to game developers was a big reason why he moved from Halifax to Vancouver.

“The bottom line is a person has the right to do what they want and it didn’t used to be that way. Halifax used to be very cut throat, people got angry. There was a very limited talent pool and if you still wanted to have one of the huge talents, that would be at a loss to somebody else,” says Wright.

Jeff Cameron, one of the co-founders for Bedford-based studio Alpha Dog Games and vice-president of the Interactive Society of Nova Scotia, recalls NCCs being more common six years ago when Alpha Dog first opened.

“They’re still a thing at larger studios, but we don’t believe in them here,” says Cameron. “You’d also see these ridiculous contracts that people shouldn’t put on their employees, but unfortunately that happens.”

Shawn Woods, co-founder for Alpha Dog Games and a director for ISNS, says the studio is focusing on mobile titles and working on three games. Some of its best known games include MonstroCity: Rampage and Wraithborne – Action RPG.

Together with Cameron they oversee nine employees, the majority of which are newer developers fresh from university or college programs, with a few who started straight out of high school. Cameron, a Nova Scotia native, moved and worked in New York for a decade before moving back in 2012 to open the studio.

As for the impact of the digital media tax credit on Alpha Dog creations, Cameron says it played a big role in bringing him back to the province.

“When I left there was little to no new game development and the tax credit would be directly responsible for bringing what is now Ubisoft’s here,” he says. “So (the tax credit) gave me an opportunity to come back to work in the province.”

caption

Alpha Dog Games co-founders Jeff Cameron (left) and Shawn Woods (right).These days, Wright and other developers find Halifax’s game development community to be much more relaxed. This is due the growing pool of developers, studios, and tax credits and the developers’ own efforts.

Numerous developers in Nova Scotia helped start the mentioned ISNS, formerly the Nova Scotia Game Developers Association, where workers in the industry “advocate for interactive and video game development and foster collaboration with the industry in Nova Scotia,” according to their website.

ISNS was created for a few different purposes, one of which was to spread information about incentives available like the digital media tax credits.

“We use ISNS to help other companies like ours understand the tax credit and help the industry to grow,” says Cameron.

ISNS also has a larger purpose: to let developers know of the possible successes they could find in Nova Scotia if they decide to work here, especially if the lived in Nova Scotia before and have since moved to elsewhere in North America.

“Our mission is to talk about stuff in the gaming industry in Nova Scotia to the industry as a whole and let people know, especially those from Nova Scotia who have left, that there’s legitimate opportunities here now so maybe some will come back,” says Woods.

Therefore, instead of a decade ago when finding and keeping senior talent was much more aggressive between the studios, through ISNS and the communicative work of developers themselves a new community has fostered. Using online communication tool Slack, they discuss the provincial industry. Woods says this type of communication is “unheard of” since they technically are competitors for both new developers and the demographics their games are aimed at.

“We’re learning how to band together and growing the industry is going to help us locally more than it will competitively,” says Woods.

Cameron agrees.

“We could either wall ourselves off and try and hold onto those (developers) or work together and try and grow the talent pool right,” says Cameron.

A more positive community and less animosity makes for a better atmosphere for the developers to work in. As Nova Scotia offers more and more jobs in the industry, bringing talent from other provinces is now more common says Wright.

“It’s awesome, you can reach out to another province and bring them in because you just introduced somebody new to the pool, somebody just moved to Halifax,” says Wright. “Whenever possible we try to do that.”

NSBI

NSBI, or Nova Scotia Business Inc., works with developers in the province to not only understand incentives, like tax credits, but to recruit international studios and connect them with workers who are already here.

As mentioned, Wright connected to Gogii Games and Donovan through NSBI, and continues to receive support from the company through networking opportunities or finances, like paying a portion of the travelling costs to conferences.

“I can’t say enough good things about NSBI, even more than any other Nova Scotia government office. They’re support is unending,” says Wright. “If they agree to pay for something, they do so in a timely manner, which is crucial for an indie start-up.”

There are other ways NSBI tries to support developers as well.

“At NSBI we promote (the digital media tax credit) as what’s attractive in Nova Scotia, but it’s not the only thing we promote,” says director of communications and public affairs for NSBI Shawn Hirtle. “We try and find companies that should try and work here and we mostly do it out of province.”

A numbers game

Nova Scotia’s Finance and Treasury Board has been tracking applications sent from companies for the digital media tax credit online since October 2015.

“(In) 2015 is when we started asking for express consent from applicant companies to upload certain information on our website,” says revenue officer for taxation and federal fiscal relations of Nova Scotia Elvira Dalag.

Applications sent to the government are split into two categories:

- Part A applications: sent in during the early stages of a project. The total amount estimated by the government is not guaranteed, as the province can revoke eligibility if it feels the project has changed during development.

- Part B applications: sent upon the completion of a project. If eligibility is granted, funds will 100 per cent be granted to the company.

“Part As are based on the production budget. Part Bs are based on actual expenses,” says Dalag. “Part As are only estimates of what might the Part B tax credit amounts would be.”

2016 saw $4.2 million in applications, 2017 saw $8.1 million.

As of 2018, the province is only disclosing amounts relating to part B applications.

The charts below show which companies sought and received the most money through the digital media tax credit from 2016 to February 2018.

As for actual costs, Nova Scotia’s yearly budget reports state the province spent almost $6 million in 2011, $5.3 million in 2012, $4.6 million in 2014, $7.5 million in 2015 and $7 million in 2016 on the digital media tax credit.

Nova Scotia did not publish the costs of the digital media tax credit in its 2013 Budget Report, saying in the Budget Assumption and Schedules for the year, “the cost of the film industry, digital media, and scientific research and experimental development tax credits will no longer be netted against corporate income tax revenues.” However, it is reported that combined those credits equal $51.1 million.

Comparatively, in Quebec’s 2016 Tax Expenditures report, the province estimates and projects it spent $687 million on its productions of multimedia titles tax credit between 2011 and 2015, and projected it would spend $178 million on the credit alone in 2016.

Between 2011 and 2015, Ontario spent just over $368 million on it interactive digital media tax credit, with its highest year being $133 million in 2014. In 2016 the province spent $79.1 million on the credit. British Columbia’s interactive digital media tax credit issued $194 million between 2011 and 2015 and $65 million in 2016.

Nova Scotia has the highest rates in the country for its digital media tax credit, however Tracey Jennings with the professional services and accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers Canada says it looks good on paper, but under performs in comparison to credits in larger provinces.

“So on paper it’s a good incentive from a rate point of view, but if you look at the volume of production activity in Nova Scotia, you’re going to see that it doesn’t even compete,” Jennings said.

That said, Nova Scotia has a much newer digital media industry compared to the larger provinces, and has a much smaller populations size at 953,000 as of 2017, according to Statistics Canada, while Quebec has 8.3 million, Ontario has 14.1 million, and British Columbia has 4.8 million.

Struggling for eligibility

While some studios are finding success in Nova Scotia due to factors like a growing talent pool and larger tax incentives, others haven’t been as lucky.

One example is a digital media production house that ended up taking the provincial finance department to court in September 2012. They the government failed to supply the company, Stitch Media, with the tax credit refunds it felt it rightly deserved.

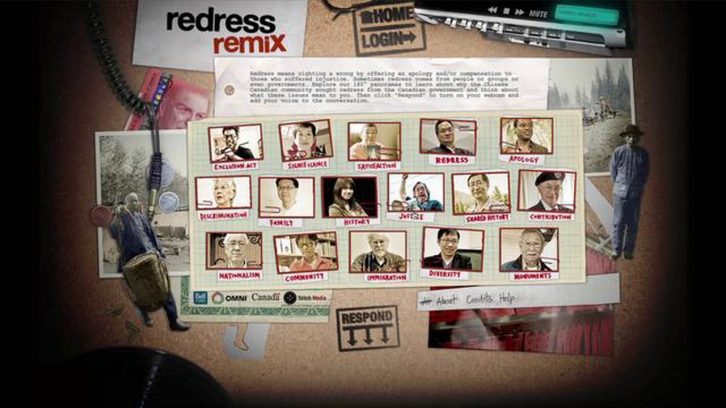

An award-winning company, Stitch Media created an interactive product entitled Redress Remix that consisted of a three-part documentary series addressing the 2006 apology to the Chinese Canadian community for the Head Tax and Exclusion Act of 1923.

It included 180-degree panoramic interviews, an interactive website, specially composed music and allowed users to record questions and opinions with their webcams which could be shared on the site.

caption

Redress Remix features an interactive living documentary website where users can see different points of view from the various interviewees.Opening in 2008, one of the reasons Stitch Media chose Halifax was due to digital media tax credit.

When CEO of Stitch Media Evan Jones filled out an application for the credit, he says he received a very “terse” letter from the Minster of Finance saying his projects were not interactive and therefore not eligible.

“I never saw any evidence there were consultations with subject matter experts,” says Jones. “These terms were defined in a way that didn’t match any definition of the words in any of the other jurisdictions.”

With no appeal process available to him, Jones took the case to Supreme Court to challenge the government’s definition of interactive, his projects would be ineligible.

“I attempted to appeal this in the only way that was available to me, there was no appeal process about this decision and there was no transparency about this decision,” says Jones.

Nova Scotia Supreme Court ruled in favour of Stitch Media, stating the finance department failed to provide the due diligence in disallowing the tax credits to the company.

When Jones then filed another application, he was once again denied but this time the letter was more detailed.

“When the follow-up decision came through, it was a much more legal version of what the original decision said, but was obviously carefully vetted,” says Jones.

This caused Stitch Media to move from Halifax to Toronto, where it now qualifies for a 40 per cent tax break on labour costs.Stitch Media lost approximately $100,000 when they were denied the tax credit in Nova Scotia.

Jones says the Ontario interactive digital media tax credit covers the projects he is working on now, and he does not believe they would be eligible if his company was still in Nova Scotia. Due to this, the province lost a company that, as of 2018, has over 10 employees in Toronto.

Another more recent case of a company questioning the government’s definition of interactivity is when the Halifax Herald Limited challenged the Minister of Finance and Treasury Board of Nova Scotia in provincial Supreme Court in September 2017.

The Herald had developed an app in 2016 for its news site allowing users to navigate various web stories and features. When an application was filed for eligibility of the digital media tax credit, it was denied stating the product was not interactive and therefore did not qualify.

The case’s court documents state director of the taxation and federal fiscal relations division, Paul B. Davies, wrote on behalf of the Minster of Finance saying, “we do not consider the user to be ‘interacting’ with the product as required in the regulations. The user is essentially a spectator who chooses which news is to be viewed. Although the user may interact with other users by commenting and sharing links, this is not interacting with the product itself.”

Representatives of The Herald disagreed with the Ministry of Finance’s definition of interactive, saying in the document, “the Minister does not enjoy ‘untrammelled discretion and cannot apply higher standards where there is no basis in law to do so.”

Companies who are denied the tax credit, due to the province’s definition of interactive, say reasons behind the denial could be subjective to whatever government official happens to receive and review their application.

“This is the controversy of the tax credit: what is interactive media?” says Jones.

There are game studios close for other reasons, despite the digital media tax credit being available to them.

For example, in 2015 game studio Orpheus Interactive closed abruptly when they were working on an episodic game based on the TV show Sons of Anarchy called Sons of Anarchy: The Prospect. Ten episodes were planned, but only one was released.

caption

Orpheus Interactive released only one of nine episodes for Sons of Anarchy: The Prospect before closing.The game was published by Fox Digital Entertainment and developed by Orpheus Interactive, through a partnership with fellow Halifax-studio Silverback Games. It was available for iOS and PC devices. After the closure, all related social media pages and the game were seemingly abandoned after the first episode on Feb. 1, 2015.

With each episode costing $2.99, a $14.99 season pass was also available with the promise remaining episodes would be released in the coming months. However in early 2016 refunds were issued on iOS and Orpheus seemed to disappear from the internet.

For a short time, the Orpheus Interactive support site hosted a message attempting to explain the delay, saying “Our team is hard at work on episode 2-10 of Sons of Anarchy: The Prospect. We will release all information via our SOAgame.com site and social media channels when new episodes or developments are ready.” The support site is currently offline and has been since early 2016.

“The company essentially ran out of money and had to stop operating because of that, there were a lot of factors that contributed to that and the tax credit wasn’t really one of them,” says Dionne, who was a producer with Orpheus at the time.

One of the tax’s credit stipulations is that a company only receives the credit when their project is finished. Dionne believes the company never actually received the credit, despite The Prospect likely being eligible because Orpheus closed so quickly after the release of the first episode.

“That said, it was super dramatic. There was a lot going on there,” says Dionne. “We had a lot of fundraising problems independent of the tax credit.”

Having had experience dealing with the tax credit in both Ontario and Nova Scotia, Dionne says if a game studio was planning on moving somewhere in Canada, financially, it might make more sense to set up in Ontario.

“(Nova Scotia) can make for a pretty interesting approach … living in Halifax, it’s a cool city, a really dynamic and interesting one,” says Dionne. “My suggestion to somebody coming in from outside and unfamiliar with Canada would be to look at Halifax and see if it’s what they want and if not, then go to Toronto or Montreal.”

Reform declaration

While the digital media tax credit can help video game development in Nova Scotia; it is also a risk. A company may finance a project, thinking they’ll receive the credit, and the province doesn’t find them eligible.

“My argument is if we want to have a games tax credit, then we should have a games tax credit, but we don’t,” says Jones. “We have a digital media tax credit and there is an enormous surge in innovative forms of storytelling, and (Nova Scotia) doesn’t seem to be appreciating the broadness of projects that could exist within that definition.”

For example, while Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia look to include virtual and augmented reality technologies in the guidelines for their digital media tax credits, Nova Scotia has yet to address their eligibility.

In the court documents for the Halifax Herald v. Nova Scotia Finance case, a statement from the Minster states, “as for the concept of augmented reality (and virtual reality), the respondent notes that these terms are not defined in the legislation and are not relevant to the court’s determination.”

In his statement, Jones expressed his concern.

“It should be troubling that innovative new technology is considered irrelevant to a conversation about this tax credit’s proper application,” he said.

In a 2014 Nova Scotia Tax and Regulatory Review by President and CEO of NSBI Laurel Broten, she says the issue, with a more subjective definition of interactivity, is possibly due to the financial limitations of the province to invest more in that sector.

“The current eligibility is narrowly defined as interactive digital media content, and the constantly evolving sector is seeking a broader definition of eligible activities. Expanding the base of eligibility may not be possible given the fiscal realities of the province. The term interactive, however, is highly subjective and lacks clarity,” says Broten in the review.

To improve the usage of the digital media tax credit in the province, Broten suggests the following in the report:

- Use industry-led expertise to determine eligibility.

- Eliminate the $100,000 marketing and distribution allowance, as this is more closely aligned with video games and does not reflect activities of the broader sector.

- Funding received from government and government agencies should be deemed ‘government assistance’ and not eligible for the tax credit.

Editor's Note

This story was completed in fulfillment of requirements in the King's MJ program. The reporting was completed between January and April 2018.

J

Jay