Unmaking a murderer

caption

A suspect's face is censored in this photo illustration.Reporting on murder without glorifying the killer

Journalists tell stories about people from all walks of life: government officials, athletes, business owners, community members and – sometimes – cold-blooded killers.

Tom and Caren Teves were on vacation in Maui in 2012 when they got the news: their beloved 24-year-old son, Alex, had been gunned down in a Colorado cinema. Between frantic calls to the police and family, they turned on the news. Photos of the killer’s face were plastered all over the screen. There he was – red-haired and wide-eyed – singed into their memories forever.

The couple found out that Alex had been killed trying to shield his girlfriend from the bullets.

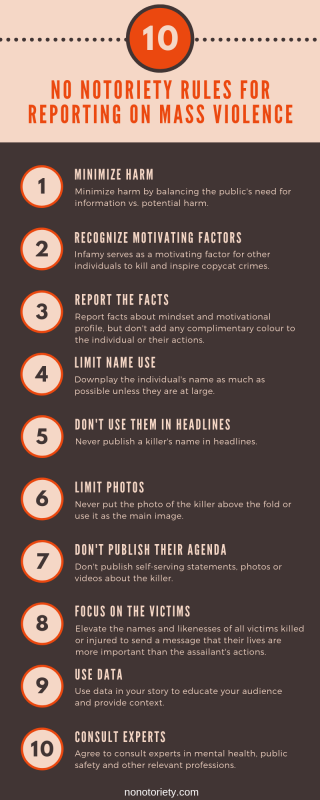

Just a few days after the murder of Alex, the Teves family founded an online campaign called No Notoriety. It calls for journalists to limit the name and face of killers in the media.

According to Dr. Michael Arntfield, a criminologist, author and professor at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario, there’s a fine line between documenting a horrendous crime and glorifying a psychopath.

Fortunately, there are strategies to report on horrific crimes such as school shootings and terrorism without glorifying the perpetrators.

Arntfield says that journalists should not place excessive focus on the killer. That means showing the killer’s face as little as possible and never sharing their social media posts.

“The media needs to transparently depict these people as disordered losers instead of making them spooky villains,” Arntfield says. “Instead of inscribing them with all these mysterious qualities, let’s call them what they are, which in most cases is psychopaths.”

Don’t Name Them is another online campaign. It was created by the ALERRT Center at Texas State University. The Center has experience training law enforcement and media how to respond to shooters. ALERRT has partnered with the FBI, and received over $56 million in federal and state funding.

Don’t Name Them has a simple mantra: don’t sensationalize the names of shooters in police briefings or in reporting. They also link to No Notoriety, the campaign started by the Teves family, on their website.

Arntfield co-authored a study of the 2017 Las Vegas massacre with D.J. Williams, a professor of social work at Idaho State University. In their study, Arntfield and Williams cited an article published in the American Behavioral Scientist journal. Written by Adam Lankford, a criminology professor at the University of Alabama, the paper is called Don’t Name Them, Don’t Show Them, But Report Everything Else: A Pragmatic Proposal for Denying Mass Killers the Attention They Seek and Deterring Future Offenders.

In the article Lankford says, “Many mass shooters have explicitly admitted they want fame and have directly reached out to media organizations to get it.” Arntfield and Williams agree that mass shootings are often motivated by desire for attention.

Williams says shooters often have core motivators including terror, revenge and power. He says journalists should focus on the families of the victims instead of the shooter. Giving the shooter media attention could be giving them exactly what they want – and hurt the families of victims.

Reporting on a killer

When and how should a journalist report on a killer?

Rick Mofina was a Calgary journalist for 20 years, and one of the first Canadian reporters to fly down and cover theColumbine shootings.

Mofina remembers at one point sitting face-to-face with Ronald Allen Smith, a killer on Montana’s death row. Their knees were touching and Mofina was uncomfortable. He remembers the prison guards smirking as Mofina and Smith sat there.

He thought interviewing Smith was necessary after speaking with the family members of the two people he killed. They had unanswered questions and wanted the killer to experience the pain they were subjected to.

There was nothing glorious about Smith. Mofina says Smith told him said he wanted to know what it was like to kill. He also told Mofina he wanted to die in prison.

When Mofina met Smith, he felt Smith had an agenda and wanted media coverage. “I don’t often talk to a human being in chains, a man who has a monstrous past.”

Still, he says meeting the killer was anti-climactic. Mofina’s goal was to describe the family’s experience over the years, instead of focusing mainly on Smith.

Mofina also recalls sitting in the newsroom of the Calgary Herald when a story broke on the radio: a boy walking beside his mother, cleaning up litter on a highway, had been killed by a truck.

“He was just a little boy,” says Mofina. “Must have been five or six.”

Mofina phoned the boy’s mother hours after the incident.

“She described it and I’ll never forget it,” says Mofina. “The wind had caught a little piece of paper, which had floated up to the shoulder of the road and onto the highway, just as a pickup truck with a trailer came by. It all happened right in front of her.”

“She said that paper was God calling her child.”

Mofina says he speaks to the family members of victims – whether of intentional violence or tragic accidents – because it can be important to them to describe their loss.

Crime reporting guidelines

Chris Hanson, a Maryland University professor who worked as a reporter for Time, the Washington Star, Reuters and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, says it’s important to avoid glorifying the killer.

Hanson says reporting on violent crime should be fact-driven and that a journalist should never use it as an opportunity to voice their own opinions. “Facts speak for themselves.”

“Try to focus on the victims rather than the shooter, and convey how much damage has been done to the families. Any efforts of the community to pull together afterwards is important to include in the coverage.”

Hanson says it’s best to give the criminal as little attention as possible. Do not try to unveil additional details about the killer. Report on the victims’ families instead.

The No Notoriety campaign makes this recommendation: limit the killer’s name to once per article.

Brendan Elliott, a Halifax City Hall official and former crime reporter, remembers the 2014 Moncton, New Brunswick shooting of four Mounties.

Elliott says, “Mainstream media has a responsibility both ethically and relationship-wise with their audience to make sure what they’re putting out there is both tasteful and accurate.”

Elliott thinks journalists should report on violent crime in a way that is sensitive to the victims and their families. Information about killers should be limited to context.

It can also be important to mention details about the killer before they are apprehended. If law enforcement is still looking for a killer, mentioning them could assist the public in bringing them to justice.

Jooyoung Lee, a professor of sociology at the University of Toronto, studies gun violence and taught a course on mass shootings. “Family members are super-traumatized by the aftermath of these kinds of events. It makes it even worse when they see the faces of the people who killed or injured their loved ones. It’s almost like rubbing salt in their wounds.”

He says the solution is to refrain from sharing many details about their personalities. The focus should never be on the killer. The killer should remain a minor detail in the story and their personality is never worth mentioning.

Not celebratory

Later in his career, crime journalist Rick Mofina interviewed Jerry D. Bigelow, who had been acquitted of first-degree murder and granted another trial. Mofina planned to write a feature on Bigelow because was about to be the first Canadian man to get off a U.S. death row.

Mofina wasn’t sure if Bigelow was innocent or guilty, and wanted details. “Then I read a story that he was arrested in Northern Ontario for breaking into a place and beating an old man until he was dead.”

In the middle of the night, the phone rang at Mofina’s house. It was Bigelow calling. He had called the Calgary Herald, who redirected the call to Mofina.

Mofina missed the call and Bigelow was found dead the next morning, hanging in his cell.

“He had an agenda,” says Mofina. “He thought we were going to write a celebratory story about a guy getting off death row, but there were still questions about his guilt.”

Mofina warns that criminals who seek news coverage may have agendas, and journalists should recognize that.

Mofina’s experience interviewing people convicted of serious crimes has taught him to be cautious when reporting on them. He advises other journalists to do the same, and to avoid focusing on them.

It takes a thoughtful, informed journalist to ensure that news and criminal agendas don’t become entangled.

About the author

Nader Nadernejad

Nader Nadernejad (born August 28, 1997) was raised in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. He is a YouTuber and Fullscreen partner, having gained viewership...