Covering Cuba

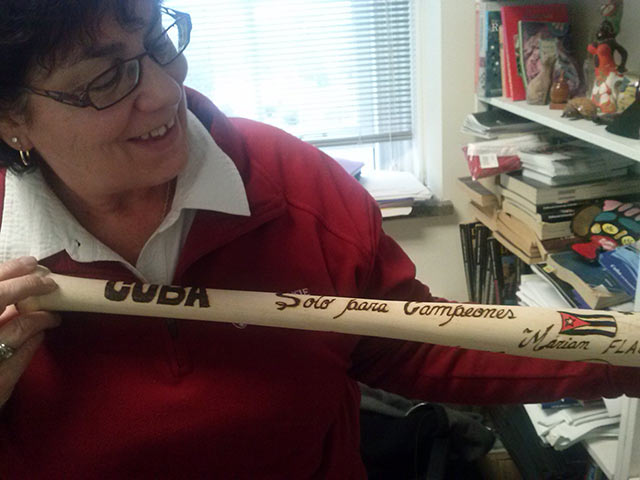

caption

MacKinnon holds a bat.Canadian journalists present non-American view of the communist island

Marian MacKinnon doesn’t look like the Che Guevara type. Her strong Cape Breton accent and habit of calling everyone “dear” establish that right away.

But if the Argentine revolutionary were alive today, he and MacKinnon might have a good time swapping stories of their shared passion: Cuba.

MacKinnon is director of the Cuba programme at Dalhousie University, and says she’s been to the Caribbean island more than 40 times since her first visit in 1997. MacKinnon brings university students to Cuba and coordinates their studies.

She finds students rarely know what to expect from Cuba. “You hear a lot about Cuba in the media,” she says. Journalists, in her opinion, “don’t tell the full story.”

Oakland Ross is a reporter for the Toronto Star, and was Latin America correspondent for the Globe and Mail from 1981 to 1986. In both jobs he has made many trips to report on Cuba. He says it’s important for Canadians to get Canadian perspectives on global news. “We’re not the U.S.,” says Ross. “It has its own interests, its own geopolitical designs, and the media reflect this. That isn’t the same as Canada’s perspective.”

The best way for Canadians to get news from Cuba, Ross says, is from Canadian journalists reporting from the ground.

Due to the closure of overseas news bureaus around the world, a uniquely Canadian perspective is not always communicated within Canadian media; often it is replaced with an American view. This creates a sort of feedback loop, where the same stories with the same perspective give the public news that is factually accurate, but may be based on non-Canadian presumptions. This may be especially true in the case of Cuba.

Ross says the closure of overseas bureaus of Canadian news operations is “worrisome in every conceivable way.”

Coverage of Cuba in North American media focuses on political issues, including human rights. Within these stories, the Canadian news media tends to treat Cuban issues differently than their American counterparts. Following Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution the U.S. imposed a trade embargo. Canada, on the other hand, has maintained diplomatic and trade relations with Cuba.

“It was all about being different from the U.S.,” says Heather Nicol, a professor at Trent University in Peterborough, Ont.. Nicol has conducted several studies on the portrayal of Cuba within Canadian media. “Sort of like giving the U.S. the finger in the newspapers.”

Since the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Canadian coverage has steadily been changing. A 2010 article Nicol wrote for the journal Canadian Foreign Policy concluded that Canadian media is generally “ambivalent” towards the Castro government.

Nicol says the Canadian media has, over the last couple of decades, begun to focus more on the issue of human rights in Cuba. This has been a staple of the American media’s portrayal of Cuba since relations went sour in 1962. “There’s a much more critical thread,” Nicol says of the focus on human rights. “A sort of Americanization.”

Incredible bureaucracy

Sending reporters to Cuba is difficult for more than just financial reasons. Catherine Porter, a columnist for the Toronto Star, visited Cuba in 2012 and wrote two stories. “It’s unlike any journalism you do in Canada,” she says. “The bureaucracy is incredible.”

Before flying to Cuba, Porter had to apply for a journalism visa and explain the story she wanted to write. She focused on Cuba’s internationally renowned medical school, the Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina. The government prearranged all of her interviews. She wanted to follow a teacher around for a day, but was not allowed to, for unexplained reasons. “They kept telling me ‘oh, we’ll try tomorrow,’” she says, “and it ended up not happening.”

Porter didn’t mention the second story she planned on writing, a profile of dissident blogger Yoani Sanchez.

There’s a ready appetite for stories from Cuba

Oakland Ross, Toronto Star

Despite logistical difficulties, especially when trying to contact Sanchez, Porter was able to come away with two lengthy stories. One paints Cuba in a positive light, while the other focuses more on negative aspects of the country. Neither story is what Heather Nicol’s studies would term “derogatory”. Those types of stories are ones that treat Cuba as a backwater, an embarrassing communist dictatorship perpetually on the verge of collapse.

Any story on Sanchez can be written in an unfavourable tone towards the Cuban government, but there is a difference between a critical tone and a derogatory one.

Porter’s story emphasizes Sanchez’s humanity, the fact she is a relatively ordinary woman facing extraordinary circumstances. The story is about Sanchez, not the Castro government. It has several direct quotes and paints a picture of what Sanchez’s life is like, including the restrictions she faces as a prominent political dissident.

It does not just talk about Sanchez’s politics, but about who she is as a person. This story stands in sharp contrast to a 500-word editorial about Sanchez published by the Washington Post on March 20, 2013.

The Post headline reads “Cubans are losing their fear of Castro regime,” but doesn’t quote any Cubans other than Sanchez. Rather than trying to tell a story about Sanchez, it sticks to political generalities. Sanchez is treated as a political figure of democracy and freedom, rather than a person with her own thoughts, opinions and experiences.

These two stories highlight one of the major differences between Canadian and American media reporting on Cuba. Porter’s story is a “slice of life” feature that uses a negative tone to describe the Cuban revolution. The Post editorial makes little effort to provide the reader with any idea of what Sanchez’s life is actually like, only what she thinks about the state of political dissidence in Cuba. It is a story about how the Cuban government is bad. Sanchez is a source, not a subject.

One major difference between Canadian and American portrayals of Cuba may be the target audience. In the U.S. a major consumer of news from Cuba is the Cuban expatriate community. Bob Huish, a professor of international development studies at Dalhousie University, says the Cuban expatriate community has deeply entrenched political views.

“They tend to see Cuba as a place that needs change,” he says. “There’s this vision of the glorious homeland that they want to return to.”

Favourable impression

Canada doesn’t have a significant Cuban expatriate community. Citizenship and Immigration Canada says only 938 Cubans immigrated to Canada in 2011, whereas the U.S. has roughly 45,000 Cuban immigrants each year.

Most Canadians today view Cuba as a vacation spot. In Ross’s words, it’s hard to find a Canadian who hasn’t been to Cuba.

Peter McKenna, a professor at the University of Prince Edward Island, has contributed op-eds on Cuba to newspapers across the country. He says tourism shows the Canadian public has a more favourable impression of Cuba than Americans.

“The Canadian people are making the distinction,” he says, noting that Canada sends over a million tourists to Cuba each year. “Even the Harper government doesn’t follow the U.S. (on the trade embargo).”

Ross says Tourism is a reason to have a distinctly Canadian perspective on news from Cuba. “Obviously, there’s lots of countries.” he says, “and not every newspaper can cover them every day. But 40 per cent of Cuba’s tourists are from Canada, and you can relate to what you read, what you see on TV. So there’s a ready appetite for stories from Cuba.”

Because of the restrictions the Cuban government imposes on its press, some people believe any news coming out of Cuba is effectively propaganda for the socialist government. Ross says this isn’t the case. “It’s not that they’re opposed to negative coverage,” he says.

Ross says it’s possible to be critical of the Cuban state and still be granted journalism visas. Even though the Cuban authorities are “intensely aware” of what gets written in foreign media, he says, they love stories about Cuban culture, be it baseball, music, or Santería, a religion analogous to Haitian voodoo. “You write those,” he says, “and they’ll go ‘oh, he hit us here, he hit us there, but he’s okay, he’s open-minded’.”

A common refrain from reporters, tourists, and Cubans themselves, is that there are good and bad sides to the socialist state. Catherine Porter said she found Cubans to be “very hospitable” and that most Cubans were comfortable saying there are positives and negatives within Cuba.

When writing her story on Yoani Sanchez, Porter says, she made no efforts to toe any political line. In other words, she tried to avoid making Sanchez out to be either a hero or a villain.

That was a bit more difficult with her medical school story. The system of schooling is amazing, she says. “I was astounded at the scope. And nobody’s reporting it!”

A search on news media database Factiva shows just two articles on the Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina in major Canadian newspapers: Porter’s, and a Globe and Mail story from 2005.

Cuba’s health care system is arguably the crown jewel of Castro’s revolution. Cuban doctors are barely mentioned in North American news media, and when they are it’s usually as an aside in another story, like the 2010 Haiti earthquake. It was while covering the earthquake that Porter first tried to write about Cuban doctors. She had no luck. “[The government] won’t let you interview them,” Porter says.

Two years later, she managed to write her story. She had to travel to Cuba to do it, and says there’s no way she could have done it otherwise.

There’s good and there’s bad, says Ross, and being on the ground is absolutely essential for someone who wants to write about Cuba. “It’s the same as any story,” he says. “You can evoke the sights, the smells, the tactile realities of a place if you’re there.”

When Marian MacKinnon of Dalhousie University says her students don’t always hear the “full story” from reporters, this is what she means. For Canadians, Cuba is not just a communist dystopia, it is a real place where Canadians continue to go. The sights, smells, and tactile realities Ross mentions may not be part of the American perception of Cuba, but they are real to Canadians. And without journalism done by Canadians, for Canadians, we will not get to hear them.