Making up the difference

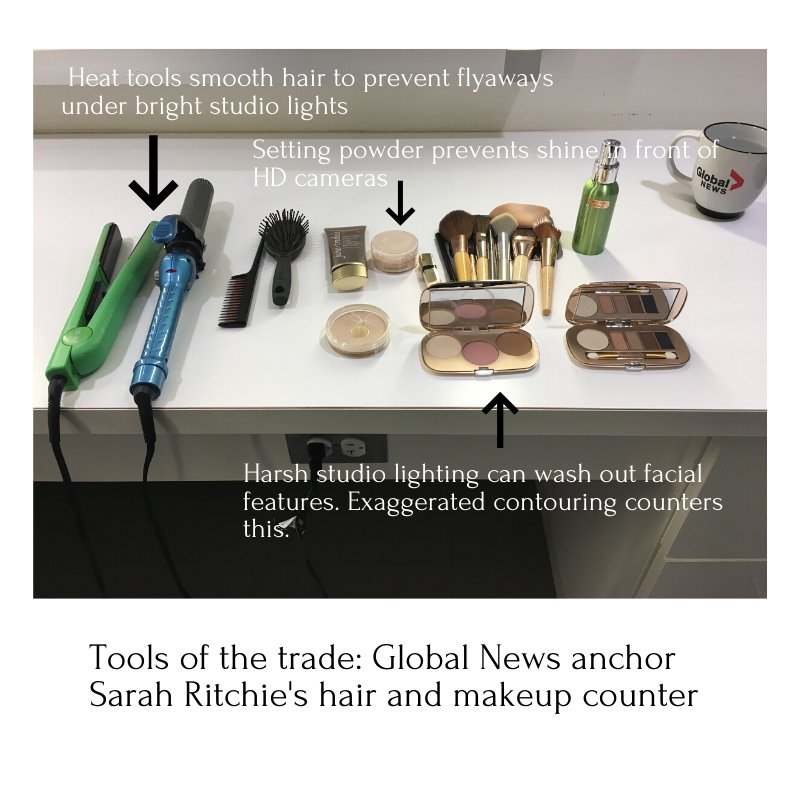

caption

Women broadcasters are expected to look a certain way.

For men, anything goes.

Reporting from Province House in Halifax, Sarah Ritchie spent countless hours in the “excellently lit” bathroom, preparing for her standups. But she wasn’t writing her lines, or fact-checking statements made by MLAs. She was putting on makeup.

Along with camera equipment, microphones and recording devices, female TV journalists often carry with them mascara, hairspray and lipstick. They devote hours each week to getting camera-ready, hours that male journalists spend working.

“Makeup is an essential part of the job,” says Ritchie, now a Global News Halifax anchor. “I can’t tell you how many different public washrooms, cars, and windows I’ve used to do makeup on the fly.”

Television journalism is one of the rare fields in which women advanced not primarily because they fought for it, but because it was profitable. Despite being established in the 1940s, TV news was overwhelmingly male until the advent of marketing research and focus groups in the late ’60s.

Dr. Craig Allen, an Associate Dean of the Journalism School at Arizona State University, has done extensive research on the history of female newscasters. According to a 2003 study he conducted, the first women to appear on TV news were chosen not in response to the women’s movement of the 1960s and ’70s, but to “tap new and larger audiences.”

Focus group research by McLean, Virginia, consulting firm McHugh & Hoffman showed that viewers responded well to female reporters, and felt they improved newscast communication. By 1971, the fifty American stations that employed McHugh & Hoffman had all hired female reporters.

Doing ‘the makeup thing’

Journalists are required to embrace facts, have their feet on the ground, and tell the truth. Female journalists have the added burden of doing so from under a mask of makeup and a helmet of hairspray.

While there’s nothing wrong with putting on some concealer to feel a bit more confident staring down a high-definition camera, it does raise questions. Does the higher aesthetic standard impact female journalists’ careers? Do they resent it? Or do they simply see it as part of the job?

The answers appear to be yes. And no. It’s complicated.

Chantal Hébert, a political columnist for the Toronto Star, used to wear purple eyeliner in high school; “I’m a baby boomer.” But you would never suspect it if you’re a regular viewer of CBC News’ the National.

Her view on makeup now? “I have no time for it.”

The one concession she makes in the makeup chair: powder, to prevent shininess under harsh studio lighting. She sees her hairdresser twice a year, and that’s good enough for her – and for CBC News’ At Issue panel.

Sarah Ritchie has naturally curly hair. But you would never know it from watching her 6 p.m. show; she blow-dries it smooth multiple times a week.

Before working in TV news, Ritchie never wore makeup; she learned to apply it for work. Her days of doing her makeup in public restrooms may be over, but she still spends 30 minutes weekdays from 4-4:30 p.m. getting camera-ready. That’s two-and-a-half hours a week. “There’s no chair, because you’re on your own.” Would the feedback be negative if she were to stop wearing makeup tomorrow? “Probably.”

In her first 10 years on the At Issue panel, Chantal Hébert was the only woman. She learned a trick: letting her male co-panelists go “do the makeup thing” first. She says makeup artists automatically put makeup on women and powder on men. By letting her male colleagues go first, Hebert avoids saying no to each cosmetic she doesn’t want applied. Instead, she tells the makeup artist she only wants powder, just like the men.

Why buck convention? For Hébert, part of it is wanting to appear as authentic as possible, something she thinks lends credibility to her work as a journalist. Part of it is being allergic to most types of makeup. Even the powder she wears can sometimes be too much. When she did six-hour news specials involving powder touch-ups every half hour, she’d often get nosebleeds at the end of the day.

One day, long ago, Hébert did do full makeup. Early in her career, while working at Radio-Canada, she put myself in the hands of the makeup artist. “I went on TV and did my thing, and my mother told me that she hardly recognized me. And that was that.”

Double standards

This isn’t to say male newscasters are exempt. We so rarely see men applying makeup that when they do, it can make the news. Take Bob Herzog, the WKRC Good Morning Cincinnati anchor famous for uploading daily videos of himself doing his TV makeup. His first video, uploaded in January 2018, has more than six million views. His videos average two minutes, far shorter than the time it takes most female journalists to get ready.

Karl Stefanovic, co-host of Australia’s Today show, wore the exact same knockoff Burberry suit on air in 2014 for a year. Not a single viewer complained. His female co-host, Lisa Wilkinson, meanwhile, received regular complaints about her appearance and her outfits clashing with the furniture on set.

We expect female newscasters to meet certain aesthetic criteria because, historically, they always have. According to Dr. Mary Angela Bock, a journalism professor at the University of Texas at Austin, female journalists who stuck to feminine stereotypes were more likely to be hired and promoted. As a result, audiences were conditioned to expect the feminine stereotype.

“Men’s looks are important in television,” Bock says. “But not nearly as important as for women to look young and beautiful and sexy and perfect.”

When newscasters flout these expectations, viewer wrath can ensue. Chantal Hébert says reading comments about her on social media is “like drinking poison.”

Teri Finneman, an assistant journalism professor at the University of Kansas, says, “You have this familiar face coming into your house, at a very personal time where you’re eating supper, or you’re lying in bed for the 10 o’clock news.” This leads to viewers feeling they “know” their newscasters and are justified in publicly commenting on their appearance via social media.

Not only do they feel justified, Finneman says, they think they’re helping. Sarah Ritchie compares it to having her grandma fussing over her appearance. The viewership “takes ownership over you, like, ‘Oh, what did she do with her hair today?’”

Halifax stylist Fred Connors shows reporter Abigail Trevino shows what’s involved with getting camera ready in this time lapse video.

The Journal

While the media for policing women’s on-air appearance may be new, the urge to do so isn’t. In 1981 the Journal, a nightly hour-long TV news program anchored by Barbara Frum and Mary Lou Findlay, premiered on CBC. It was the first nationally broadcast news show in Canada anchored by two women. Frum and Findlay were both well-respected and established in their journalistic careers, but that didn’t exempt them from the visual expectations of viewers.

According to the Journal’s publicist, Ruth-Ellen Soles, fully a third of the feedback – hand-written letters – had to do with Findlay and Frum’s appearances. “It was like they couldn’t help themselves. Barbara had just finished doing an amazing, intricate, political, highly-skilled interview, and they wanted to comment on it, and it was like they couldn’t resist saying something about her hair.” As she remembers, no complaints were ever mailed or phoned in about male correspondents’ hair.

Sally Reardon, a former Journal editor who later became the first female executive producer of the Fifth Estate, says complaints about Frum’s hair weren’t due to a lack of effort on the part of Frum’s hairstylist. Frum referred to her time in the hair and makeup chair as “death by hairspray.”

So, are aesthetic standards getting more exacting, or less? The great thing about journalists is we can all work in the same field and disagree. Reardon thinks the pressure placed on female journalists to doll it up has gotten worse, thanks to the 24-hour news cycle. More airtime to fill means more pressure to hold viewers’ attention.

Hébert disagrees. At the beginning of her career in TV, in the 1970s, female newscasters were packaged to look like “1950s airline stewardesses”, while all men needed to be taken seriously was a suit. She thinks women today have more choice in their personal presentation on TV, pointing out that if her lack of makeup was a big deal, she wouldn’t be in her fourth decade on the air. Hébert also believes female journalists have their reporting taken more seriously now than before, regardless of how they look. All of Hébert’s TV work with CBC has been freelance, which means “you can drop me tomorrow.” Clearly, they haven’t.

Ritchie hasn’t been on TV for long, but she feels it is important to look “polished.” While she isn’t contractually obligated to do so, she does feel it would distract from her work if she were to suddenly stop blow-drying her hair smooth and applying makeup. “I’ve never tried. I don’t think it would fly.

About the author

Abigail Trevino

Abigail is a fourth year journalism student at the University of King's College. She is also the publisher of The Watch, the university's campus...