Inquiry calls for youth, families to have more say in child-care processes

Restorative inquiry looks into the history of racism and child care in Nova Scotia

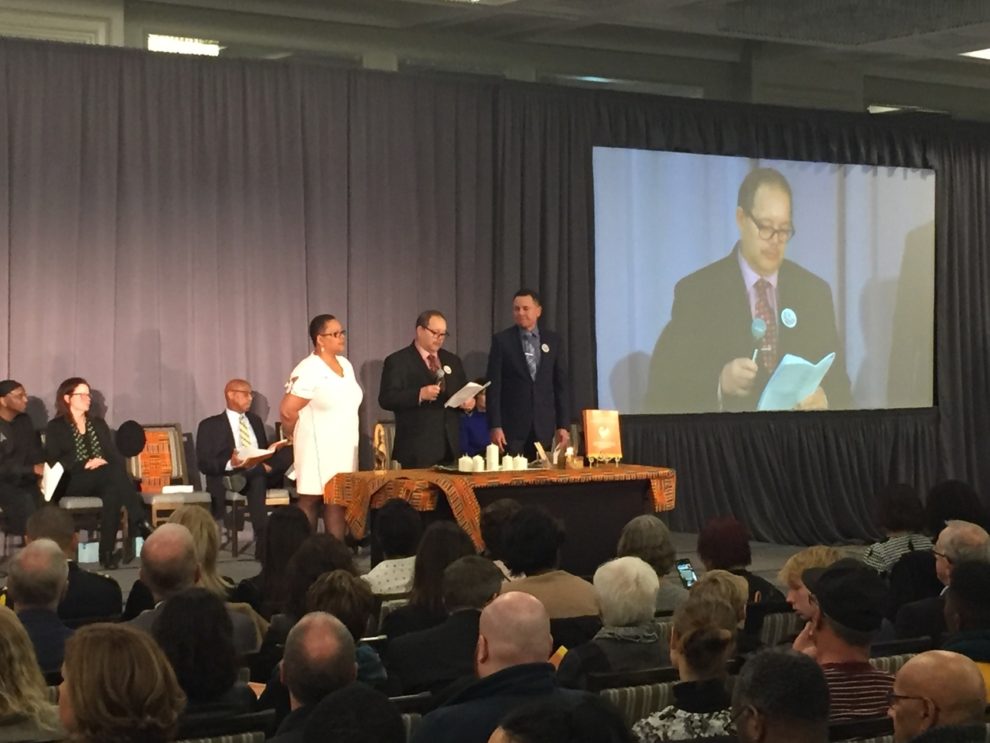

caption

Members of the restorative inquiry present the final report: Tony Smith, Pamela Williams, George Gray and Tracey Taweel.Nova Scotia needs to create human-centred systems to empower vulnerable residents, according to the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children restorative inquiry.

On Thursday, the Council of Parties released its fourth and final report, at 556 pages long, during a closing ceremony in Halifax.

Tony Smith, the first former resident to publicly speak about the abuse he experienced at the home, said he is honoured to have people learn about these harms to build a better future.

“The burden of shame is a badge of pride,” he said before the ceremony. Related stories

caption

Three former residents spoke at the closing ceremony. Tracy Dorrington-Skinner, Gerry Morrison and Tony Smith.The report is part of a restorative inquiry into mistreatment at the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. The orphanage opened in Dartmouth in 1921 because other homes rejected black children, and closed in 2015. Throughout that time, 1,800 children lived in the home. Smith, now co-chair of the inquiry, spoke out about his experiences in 1998.

The inquiry found that the way systems, like the child-care system, are run leads to unmet needs.

“We need a fairly fundamental shift in terms of the ways in which we are working in our system of care,” said Jennifer Llewellyn, the restorative process adviser and a law professor at Dalhousie University.

Llewellyn said systems have silos, which is when departments or processes are grouped separately and don’t share information. The inquiry calls for a human-centred system to get rid of these silos and allow youth and families to engage more in the decision-making process. Human-centred systems, Llewellyn said, allows for relationships which build trust and communication.

The inquiry also called for further education on Nova Scotia’s dark past.

For Smith, education is essential in respecting culture. He said he would like high schools to look into black history and learn what happened in the Home for Colored Children.

“We have been here for 400 years and we have suffered,” said Smith.

He said after contacting the Black Cultural Centre, there will now be a display about the home.

Since 1998, more former residents have come forward to tell their stories of physical, psychological and sexual abuse. This led to settlements worth $34 million, a formal apology from Premier Stephen McNeil in 2014 and the establishment of the restorative inquiry in 2015.

This is the first restorative inquiry in Canada. A traditional inquiry has a government or legal authority determine the process, but a restorative approach allows affected parties to work together. Llewellyn said this latter approach creates “a safe and open place” where affected members would be more willing to open up.

caption

Premier Stephen McNeil received the report and made his remarks to the public.McNeil received the final report of the inquiry at the closing ceremony. During his remarks, he spoke about systemic racism in Nova Scotia.

“I believe that if we remain silent, we are continuing in the journey of our ancestors, which is unacceptable,” McNeil said.

He called the inquiry a “collective journey” where Nova Scotians must learn the history, accept their roles in it and change for the better of the next generation.

About the author

Madeline Biso

Madeline Biso is a student journalist at University of King's College. Her main interests are investigative and data-driven stories. When not...