A new legacy

caption

Leaving legacy media to build their own ventures means journalists have to learn business skills.Racialized journalists in Canada are reclaiming their power

Matthew DiMera no longer believes in legacy media. After completing journalism school at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Surrey, B.C. in 2015, DiMera had what virtually every aspiring reporter in Canada coveted: entry into a mainstream newsroom.

Their first paid job was in local broadcast news. The environment at legacy media outlets overall was tough.

“As someone who was Black, as someone who was queer, I realized I was going to have to change a lot to fit into their mould,” DiMera says. “And even then, I knew I wasn’t actually going to fit.”

DiMera later became a managing editor at Xtra in Toronto.

In 2019, they pivoted to an alternative news site, becoming rabble’s interim editor-in-chief. DiMera was eager to finally change the system from within. But it didn’t happen. “A lack of representation is an indicator that something is wrong,” DiMera says. “But having representation doesn’t mean everything is right.”

Efforts to centre more racialized voices and stories were fruitless. They quickly realized their title was really an ‘acting’ role and resigned. That’s when they lost faith.

No amount of peppering diversity into an organization’s makeup would address the systemic issues at hand: white-owned, white-led media models were never built to serve racialized Canadians. Or support racialized journalists.

DiMera identified another broken model. “At the end of the day, having multiple meetings about whether you can capitalize ‘the B in Black’ is a waste of everyone’s time,” DiMera says. Meaningful change wasn’t happening — at least not fast enough. And whatever the newsrooms’ excuses were, they were “done waiting.”

The reckoning

Across Canada, many racialized journalists are working to effect change or simply leaving legacy media altogether. Media outlets are promising improvements in equity, diversity and inclusion. But newsrooms remain overwhelmingly white-powered. This imbalance perpetuates reductive coverage filtered through white lenses that don’t speak for more than one-quarter of Canadians, who represent the global majority.

The racialized population numbers have been “steadily increasing” since 1996, according to detailed demographic projections from Statistics Canada. “In 2041, about two in five Canadians will be part of a racialized group,” the agency estimates. In 2016, there were eight million racialized people.

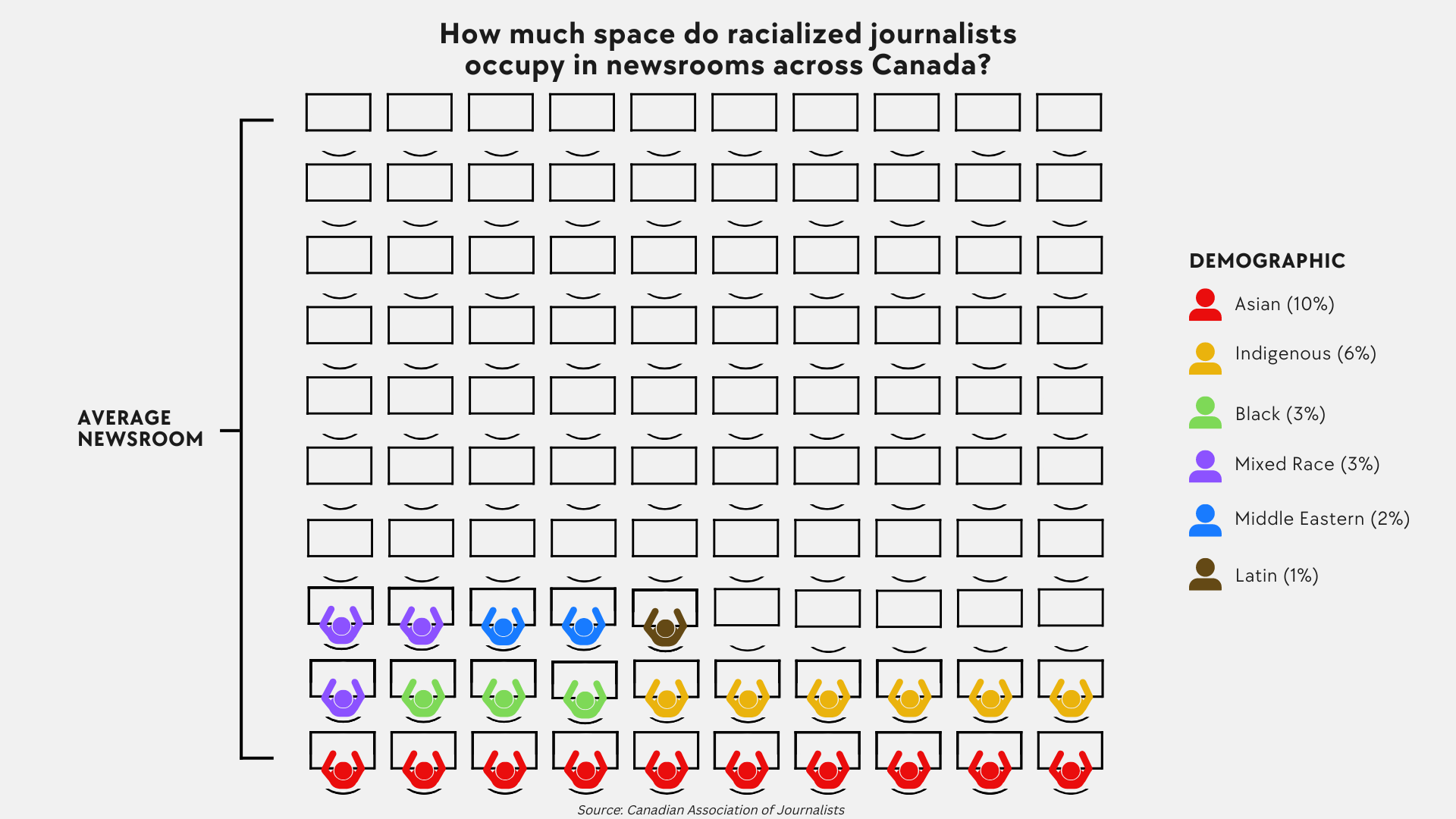

Toronto is the media capital of Canada. More than half of its people have melanin. But the mainstream newsrooms headquartered there are failing to adequately reflect the demographics. Nearly half of newsrooms surveyed don’t employ any racialized journalists, according to the Canadian Association of Journalists’ 2021 diversity report. Across the nation, 75 per cent of journalists in newsrooms are white. They hold four out of five positions of power.

Causing harm

This dominant Eurocentric lens continues to harm racialized communities. Canadian media coverage of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s blackface and brownface scandal in 2019 is a memorable example. White-led media failed to address the underlying racial and social issues at play.

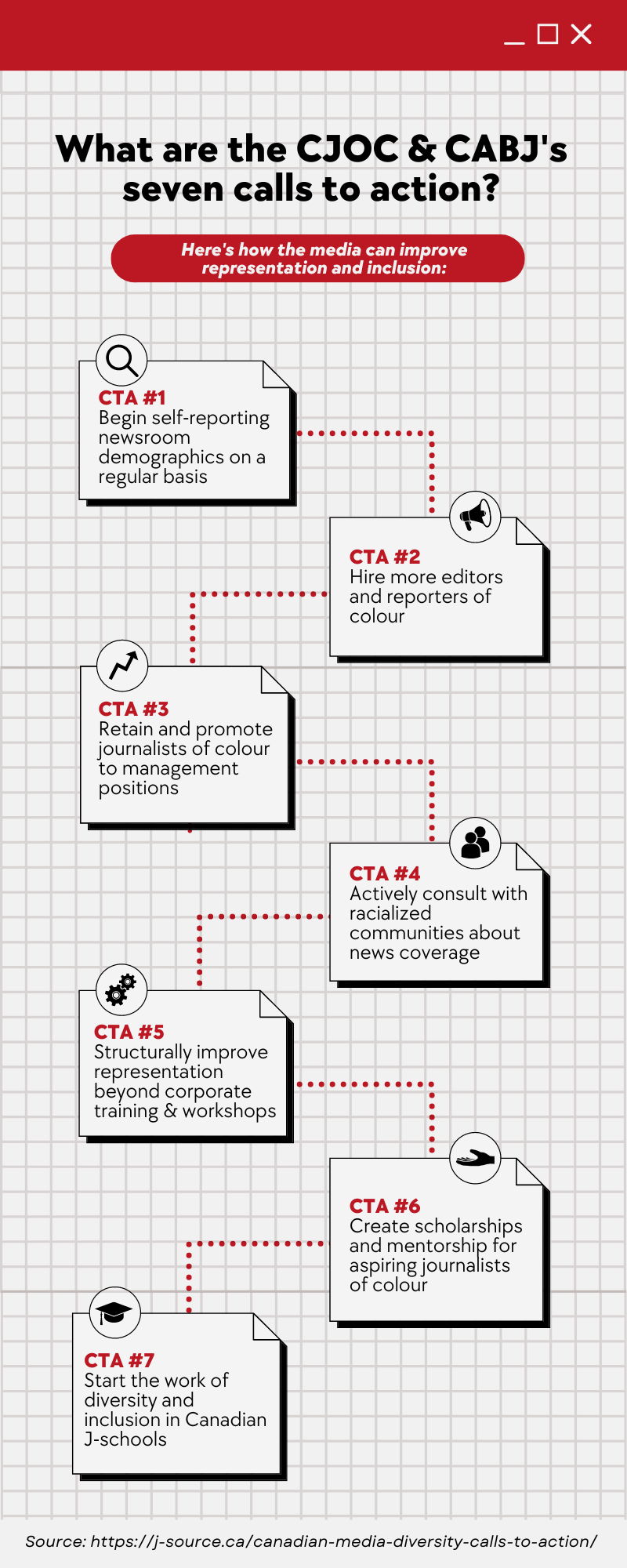

In response, the Canadian Association of Black Journalists (CABJ) and Canadian Journalists of Colour (CJOC) teamed up. In January 2020, seven calls to action were released, calling for improvements in media representation and inclusion. Although more than two dozen newsrooms were engaged, it wasn’t until the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, which sparked global protests, that legacy media — like The Globe and Mail — was forced to wake up.

Deputy national editor Mark Iype is Indian, from the Maritimes. He’s been at the Globe for about one year and believes there’s a “concerted effort” to diversify Canadian media. “It’s a painfully slow process from where I sit in our newsroom,” Iype says.

High-profile departures at Bell Media’s CP24 in Toronto are telling. Reporter Brandon Gonez started a weekly YouTube talk show in January 2021. In an interview with Complex, Gonez discussed the empowerment of ownership, stating, “ … we can call for more diversity on screen and behind the screen. But at the same time, if some people or place or platform shows you who they are, you have to believe them.”

Patricia Jaggernauth filed a human rights complaint in October 2022, alleging a “systemic pattern” of racism, sexism and discrimination during 11 years with CP24. CBC’s Shanifa Nasser had the exclusive.

Who’s the boss?

Maureen Googoo was working in a Halifax newsroom in 1998. She was the first and only Indigenous journalist there, and her Mi’kmaw perspective was initially welcomed. Editors encouraged stories on her community, Sipekne’katik First Nation. That enthusiasm dwindled.

Eventually, she was told she was hurting her career with “this Native kick” and she’d lose out on prestigious beats such as City Hall or the provincial legislature. Six months later, Googoo left mainstream media.

“In the end, the job that I really wanted to do is the one that I had to create for myself,” she says.

Googoo founded Ku’Ku’Kwes News, pronounced “Goo-goo-gwes”, in 2015. In an interview with CBC, Googoo mused, “… if Arianna Huffington can have her own website called ‘The Huffington Post’, why can’t I have kukukwes.com?”

The site is dedicated to Indigenous news coverage in Atlantic Canada. It crashed twice due to the traffic its stories have driven from Mi’kmaq communities and beyond. Now, after several upgrades thanks to crowdfunding and advertisements, she’s proud of the earned readership.

When mainstream media contacts her to cover stories, she declines. “I’m doing this for me,” Googoo says. “I’m doing this for my audience.”

Given the ongoing financial failings in the industry, Googoo doesn’t see its coverage of Indigenous peoples improving anytime soon. “I can’t feel too bad about legacy media because I’ve benefited from it. If they’re not filling that gap, I will.”

New lenses

Photojournalists provide the images accompanying the ‘first rough draft of history.’ But when Canadians retell the past, they point to the pictures dominated by a singular lens: the straight white male perspective.

Korean-Canadian freelance photojournalist Jimmy Jeong is smashing that lens. Based in Vancouver, Jeong founded Room Up Front in 2020 to help racialized photojournalists reframe how history is told. The mentorship program is bolstered by professionals aiming to support and make space for historically unseen perspectives.

“Photojournalism is no longer about parachuting in, run-and-gun, just to beat the other photographers,” Jeong says. “It’s about listening and learning and knowing about the community you’re going into.”

Jessica Lee went through Jeong’s program. She’s now among the mentors. In 2022, she wrote about becoming the “first female photographer of Asian descent at a major Canadian daily.” Being out on assignment for the Winnipeg Free Press isn’t exactly easy.

Racialized photojournalists are essential. The choices photographers make directly impacts the audiences’ point of view, bias and all. That’s why the person behind the camera — and the editorial desk they file to — is critical.

Take the essay on manicures Lee filed for The Local, under editor Tai Huynh. Or the Globe story about skyscrapers and derelict buildings in downtown Winnipeg; Lee worked with editor Taehoon Kim. “The stories we were able to tell captured nuanced details better,” Lee says. “In a way that an editor from a typical white background might not understand.”

Punctuation

There isn’t a defining moment for Lela Savić. It was a series of interactions in Montreal. Stories she pitched about systemic racism to white editors were always challenged. An editor put quotation marks around the words white privilege in a story about, well, white privilege.

Savić’s ethnic background is Romani. In her culture, it’s unacceptable to go to someone’s house and immediately ask questions. There has to be a conversation before the interview begins. To her, journalists must build relationships first and meet deadlines second.

She knows marginalized communities don’t trust the press due to its consistently harmful coverage, and recognized “the media that I wanted didn’t exist in Quebec.”

La Converse launched in 2020. It operates as a non-profit and is a community-powered media outlet. Savić’s team writes stories that come directly from the people. Archives include articles about Indigenous humour and a music studio in a youth centre.

Serving low-income communities means funding is a challenge. Savić’s main goal is achieving financial stability through philanthropy and government funding. To keep coverage accessible, she doesn’t ask readers for money. “They shouldn’t have to pay us for our content, especially given they don’t trust us.”

Money talks

Survival is the primary concern for most emerging media. Without proper funding, independent ventures can’t be sustained. Supporting this new wave are organizations like CABJ. One of its latest programs is the media startup bootcamp, funded by a corporate sponsor. Along with courses, it offers five annual startup grants of $5,000 each for digital ventures.

Last year, Toronto-based founder Matthew DiMera received one for their platform: The Resolve. As it grows, DiMera is focused on building trust through thoughtful and fair coverage. “My hope is that by doing better elsewhere, we can be an example of what is possible,” says DiMera.

But is $5,000 enough? The CABJ’s executive director Nadia Tchoumi doesn’t think so. “Any journalism funding that has come out in the past has been propping up legacy media,” Tchoumi says. “I think that is what has to change.”

Although some believe the future of Canadian journalism is emerging media, Tchoumi says otherwise. “These journalists and start-ups are not the future. They’re the present.”

About the author

Chase Fitzgerald

Chase is a fourth-year journalism student from Mississauga, Ontario.