“Every time a hurricane happens, I think of them.”

caption

Kayleigh Stevens.

Kayleigh is a 24-year-old Nova Scotian journalism student graduating from the University of King’s College in Halifax. With a love of reading, writing, and travel, she decided to study English at St. Stephen’s University in New Brunswick, hoping to become a second-language English teacher.

She fantasized about moving to Hawaii and opening up her own bookstore, teaching paddleboard yoga in the morning and retreating to the stacks in the afternoon. Kayleigh switched to journalism so she could spend her career reading and writing about a wide range of topics instead of narrowing herself down.

In her spare time, she enjoys making art and writing fiction. Kayleigh has wanted to write a book her whole life. She recently got engaged to her long-time partner, Adam. Kayleigh was staying with him at his family’s home during post-Tropical Storm Fiona in September 2022. In Nova Scotia, power outages are so normalized that many treat them as social opportunities, and Adam’s family is no exception. They were excited to play board games by candlelight and snack on storm chips.

Her own family is different. For them, power outages are anxiety inducing. Many of Kayleigh’s family members live in rural areas of Nova Scotia, where access to critical infrastructure is delicate. Among that family are her grandparents.

My grandparents have a property in Brookfield and Stewiacke. It’s on Pembroke Road, this old dirt road full of potholes. I remember when I was a kid, I had a dog named Ella and she would always ride in the back of my parents’ van. She would recognize the sound of the gravel on Pembroke Road and start crying and barking because she was so excited to go to my grandparents’ cottage.

You drive up, maybe not even five minutes, and the houses are all pretty spaced out. But then you get to this little area where there’s a couple houses that are really close together. On the right-hand side, there’s this big white house. They have dogs and, in the last six years, they got cows. On the left-hand side, there’s another full-time farmer. He’s got chickens, turkeys, sheep, and cows. And he had horses at one point. Right across the road, from his main house, is my grandparent’ house. His guinea hens always come over and they eat all the pine needles in their lawn.

caption

Kayleigh Stevens’ grandparents’ home following post-tropical storm Fiona. On the left are just a few of the more than a dozen trees Fiona ripped from the ground.It’s my favourite place. We would go up and have huge family gatherings every summer when I was a kid. It’s a really important part of my growing up. Sometimes it was upward of 150 to 200 people camping in my grandparents’ yard. Family would come from New Brunswick. Family came from Quebec at one point.

My grandparents didn’t have plumbing for a while. Every morning, we’d drive to this huge waterfall that was down the road. That’s where we would shower. We’d go and soak up in the river and we’d swim. You had to be the first one in the water, otherwise, you’d be thrown in.

Up the driveway was a lawn where would play ring toss, washer toss, and have huge bonfires. My uncles all played guitar so we would sing around the bonfire every night, roast marshmallows, and play card games.

They had this little creek into the wooded area on the left side. On the side of the creek, there was this little patch of grass. On that patch of grass, there were five or six trees. My grandfather built a tire swing and a bench swing in those trees.

Then there were my grandfather’s crabapple trees which he used to feed the deer when they would go hunting. My parents always told me that if you eat crabapples, you’ll get the shits. They’re smaller versions of apples. They only grow as big as your palm. They taste like an apple, but they’re really sour and really tart. Imagine eating those all day in the summer. They dry out your mouth. You’re so puckered up because they’re sour and it’s hot out. It wasn’t the greatest experience but I felt vindicated because I was right. I didn’t get sick.

On the other side of the creek there were trees that were sparsed out equally. That’s where we would camp. Everybody would be in their own little square, right in between the trees. If it ever rained you could string tarps over all the trees. It was cool. We were this big tarp city.

caption

“They’re never not working,” Kayleigh Stevens says of her grandparents who, despite being in their 80s, are active in maintaining their rural property.I heard from my mom that my grandparents had lost trees during the hurricane. My grandmother called my mom on their landline. I asked, “How are Nanny and Grampy? Do they have power up in the country?” A lot of people in Sambro and Herring Cove didn’t have power yet. Some parts of the city didn’t have power yet. My mom was like, “No, and they lost all the trees.”

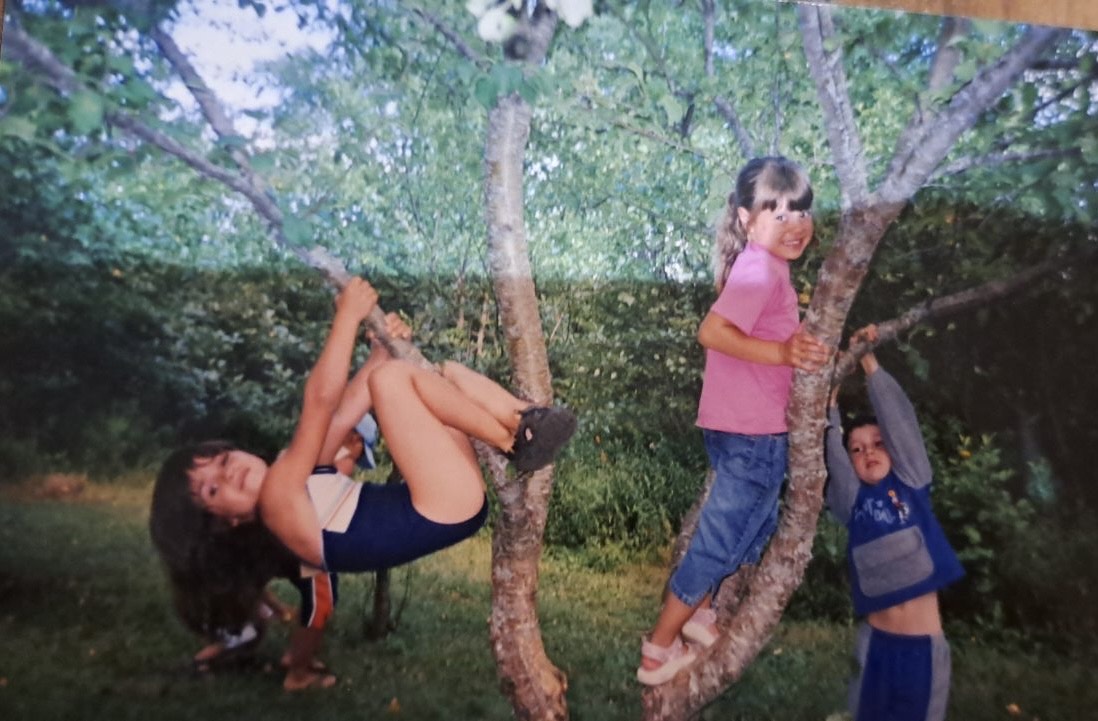

caption

Kayleigh (left) and her cousins climb a crab apple tree on her grandparents’ property in 2007. Every year, Kayleigh’s extended family reunited on the property for a fun-filled camping weekend.

caption

Kayleigh says that, while city dwellers have turned power outages into social events complete with board games and storm chips, downed powerlines and high winds leave rural Nova Scotians feeling vulnerable and anxious.My parents drove up a couple weeks later to make sure they were still okay. At that point they had power but they had lost a lot of food. My mom had taken pictures when she had gone up. When my parents came back they were like, “Oh, you have no idea. The trees are gone.”

In their yard there was probably 12 to 15 holes. The trees were completely tipped over and the ground was ripped up. No clean breaks. Just tipped right over. My grandfather and grandmother are in their 80s. They would usually be cutting up all those trees. They’re like, if we stop moving our life is going to end. They are never not working. The first thing I noticed was that the trees weren’t cut up and used for firewood yet.

It wasn’t until months later that I went up to visit, around Christmas time. It wasn’t until I saw it in person that I realized how much it changed the property. They don’t have any of the trees we would tent under. They lost all of the crabapple trees, and all but one of the trees the swings were on.

I was thinking about climate change before the storm happened. That was a common thing that was on my mind way before the storm, but the storm really made it top of mind. It made me think how drastically it can change the look of things. It literally changed my grandparents’ property, which was very significant to me growing up. It was really jarring to personally see how much space open there was. You can see right through to the other house now. It didn’t feel the same anymore. It was like a hole.

About the author

Kayleigh Stevens as told to Charlotte McConkey