Unpacking phone bans in schools

caption

An iPhone in a locked cage displays multiple notifications.Experts disagree on whether banning smartphones is a silver bullet or just a band-aid solution for classrooms

“Excuse me, phone away,” Dante Luciani tells his students. “Phone away.”

Luciani said he constantly reminds his students to stay off their devices to comply with the ban implemented at Cathedral High School, where he teaches, in Hamilton, Ont. He says these “micro-conversations” disrupt his classes.

The problem extends beyond the classroom, too. When coaching a soccer game during a physical education class, he noticed the goalie with his head down in his cellphone.

“There’s no reason to have a phone on you,” while on the soccer pitch, he said.

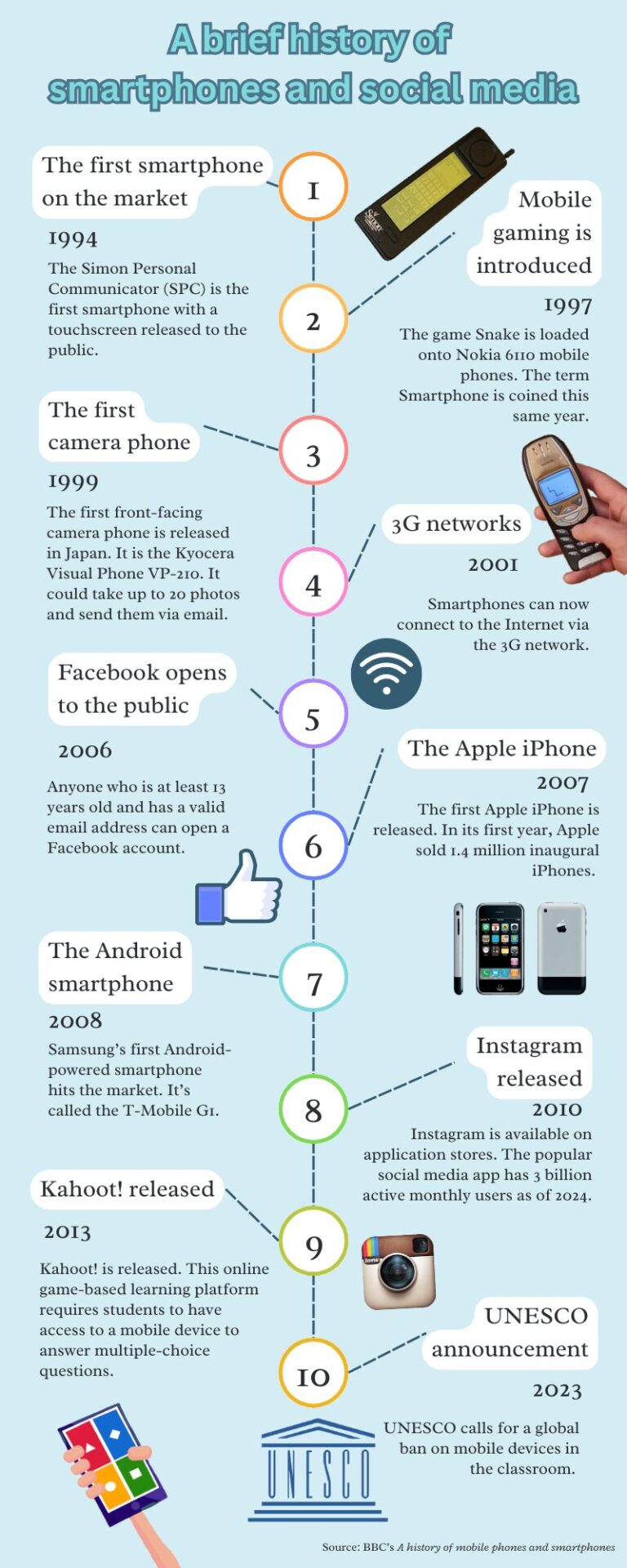

Smartphones in schools

Teachers all across Canada find themselves competing these days with the ubiquitous mini-computers in everyone’s pocket. Nearly 90 per cent of teenagers carry a smartphone, studies say, so educators are concerned about how phones affect students’ grades and well-being.

Many teachers let students use their phones as learning tools. But it can be difficult for students to pull themselves away from the little screen and focus during a math lesson.

A 2023 report from a United Nations agency said it can take students up to 20 minutes to refocus after being distracted from the task at hand.

The Global Education MonitoringReport, Technology in Education: A Tool on Whose Terms?, produced by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), said some technology can be helpful, but not when it is inappropriately used or abused in the classroom.

The study said removing phones from schools in Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom improved student performance.

After the study UNESCO called for a global ban on smartphones in schools. In the report, the agency said that a “human-centred vision” of education is better than a digital one.

Canadian schools’ reaction

In response, eight provinces restricted phones in classrooms at the start of the present school year, but there are some outliers.

Quebec restricted student phone use almost a year earlier, in December 2023. Newfoundland and Labrador is drafting a policy on the issue. The territories’ education systems don’t have a policy.

What does a ban entail?

Every province has different guidelines and schools use different enforcement strategies. Some require students to keep their phone off and away for the entire school day. Others only ban phones during instructional time or leave it up to teachers.

Some schools use the phone hotel, a plastic sheet with pockets that is hung on a wall in the classroom. When students enter the room, they put their phone in the hotel.

Luciani teaches physical education, science, and drama. A phone hotel does not help him since he moves between the stage, science lab, gymnasium, and field every day.

“Would I carry this hotel around with me all day?” says Luciani, shaking his head. “Even if we buy them, that’s another expense on the school.”

At Carleton Place High School in Carleton Place, Ont., math teacher Mike Lieff uses coloured-coded, laminated signs to tell students when they are allowed to use their phones. A red X means stop and a green checkmark means go.

He says the system helps, but he is still struggling.

“As soon as the math lesson was done, some of them wanted to play games,” says Lieff, “and it was like Whack-a-mole trying to get them to stop.”

caption

A portrait of Dante Luciani.The Anxious Generation

Games, social media, and notifications pull students’ attention away from class and into the online world. According to New York University professor Jonathan Haidt’s 2024 book, The Anxious Generation, the average young person’s social and communication apps deliver 192 notifications a day.

That number gets even bigger when other apps like games, reminders, and news alerts are loaded on their phones.

Haidt’s book covers the “great rewiring” of childhood. He says play-based childhood has ended, and phones have taken over. Cellphones, he says, are addictive and designed to monopolize attention.

Haidt said schools should be phone-free all day, every day.

“Many students with access to their phones use them in class and pay far less attention to their teachers,” he writes.

A 2020 study by a University of Toronto professor found that excessive cellphone use can harm life satisfaction, self-esteem, and self-reported happiness.

In a Canadian Medical Association Journal article titled Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health, psychiatry professor Elia Abi-Jaude also reported that mobile phone addiction disrupts sleep and concentration, so students are bored quicker.

No strong research

Andrea Howard, a psychology professor specializing in adolescent mental health at Carleton University, says the phone ban is a quick fix and easy solution to keep students’ attention. But she doesn’t think it’s that simple.

She says real, personal problems in a lot of children’s lives are being ignored because of the belief that the smartphone is to blame.

“It’s easy to forget,” says Howard. “What did things look like 15 years ago, before phones were around? Were all classrooms really chill and everybody was behaving themselves, with no problems with distractions?”

She says young people use their phones in positive and enriching ways. Marginalized children, including LGBTQ youth, can find online communities that support them when they may not have a safe place at home.

She says the evidence showing a link between smartphones and poor mental health is “extremely weak.”

All about balance

caption

Smartphones sit in the numbered pockets of a “phone hotel” as it hangs in a classroom.Nova Scotia students are not allowed on their phones during class time, but student Jordan Shedden thinks the ban is too harsh.

Shedden, a Grade 12 student at Millwood High in Middle Sackville, finds other distractions. “I’ll doodle on my page. I’ll talk to my friends. I’ll just find anything else to do other than my work.”

The ban was introduced to the students through in-class presentations. Anyone who had a phone out would get one warning, and after that it’s straight to the principal’s office.

Shedden said the phone ban is a good idea in theory. He believes some students are old enough to make these decisions for themselves, especially with the educational tools that a phone can provide.

“A phone can be very versatile,” says Shedden. “Yes, it can be distracting, but it can also be helpful.”

The ban is not policed to the same degree in every classroom. Shedden said he wishes for a more structured plan rather than a blanket ban.

The founder of a Toronto-based education non-profit believes that for phone bans to be effective, they must be part of a bigger, more comprehensive policy.

Annie Kidder is the founder and director of People for Education, which supports the advancement of public education through research, policy, and public engagement.

She recommends a policy that teaches students how to use technology effectively. “It’s all about balance.” But, Kidder says, she’s “not seeing that anywhere.”

The curriculum must advance with technology so students can learn how to use it safely. Learning “how to be a human in today’s world,” says Kidder. “That is the job of education systems.”

About the author

Anna Rak

From small town Ontario, Anna Rak is a fourth-year student in the Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) program at the University of King's College....