Off thin ice

caption

Women's hockey is quickly growing in popularity across Canada.How a major investment is transforming professional women’s hockey

Kristin O’Neill grew up a hockey player. Sleeping in her tracksuit, excited to get out of bed early to go to the rink, O’Neill’s love for the game grew throughout her childhood.

Her dream was to play for Canada – a goal she reached. With no option for women to pursue professional hockey, playing at the national level was the only goal for a lot of girls.

Today, the Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL) offers her a chance to play at the highest level. Established in 2023, the PWHL has completed one season and is set to begin its second tomorrow, on Nov. 30.

On January 2, 2024, O’Neill played for Montréal in front of 8,318 fans in Ottawa – then, a record for professional women’s hockey. It was Montréal’s first game of the season, and the second in PWHL history. “To step on the ice and hear the roar of the crowd,” she said, “was unbelievable.”

Throughout the season, O’Neill, 26, played in front of people who didn’t look like typical NHL fans. Thousands of young girls went to games, and were “able to see that it’s possible for (them) to play this sport,” she said.

In Canada – a nation that boasts its passion for the game – women’s hockey has been an afterthought. The road to a professional league has been long. And winding. And bumpy.

Playing shorthanded

Since 1999, women’s top-level hockey leagues have come and gone. The National Women’s Hockey League, Western Women’s Hockey League, Canadian Women’s Hockey League, the Professional Women’s Hockey Players’ Association, and the Premier Hockey Federation tell a story of instability highlighted by a lack of commitment – both public and private.

The PWHL wants to rewrite the story.

The PWHL is the most recent venture for Los Angeles Dodgers owner Mark Walter. He and tennis legend Billie Jean King own both the league and its teams. Together, Walter and King offer financial support that the leagues of the past simply never had.

For the PWHL, past leagues are a cautionary tale. In 2014, the Canadian Women’s Hockey League was the first women’s league to strike a broadcasting deal with a major Canadian network – Sportsnet aired three regular season games per year.

In 2015, The National Women’s Hockey League was the first to offer players salaries. The minimum salary in its first season was $10,000 CDN. A year later, this was halved.

The PWHL broadcasts games on CBC, Sportsnet, TSN, and YouTube. Walter and King offer a $35,000 US ($48,427 CDN) minimum salary for the five month season.

Will it pay off?

caption

Something you see much more often in women’s hockey than in men’s hockey: pony tails.A fresh start

“We believe we have an incredible product on the ice, a growing fan base, first-rate sponsors, and an opportunity,” says PWHL vice president of league operations Chris Burkett.

Announced in August 2023, the PWHL dropped its first puck on New Year’s Day 2024. This short turnaround demanded seven-day work weeks for league executives to finalize venues, broadcasts and partnerships.

The inaugural game, between Toronto and New York, was played at the Mattamy Athletic Centre in Toronto – formerly Maple Leaf Gardens. Now, the ice is on the building’s third floor, while the second is a gym and the first is a Loblaws.

Neither teams’ jerseys had distinct branding. Rule adjustments, like allowing body contact, left players uncertain how to play. The 2,600-seat arena was too small for an event so historic.

But 2.9 million people across Canada tuned in to watch.

The season both exceeded and fell short of league expectations. Attendance at some arenas – particularly in New York and Boston – often was far from capacity, and teams were hard to market because branding decisions were pushed to year two.

On the flip side, YouTube broadcasts generated forty million views, partnerships were made with more than 40 brands, and revenue is ahead of schedule.

Profit not the concern

“You want to make sure you’re not just a one year wonder,” says Ottawa general manager Mike Hirshfeld. “That’s obviously something you keep in the back of your mind.”

The league is seeking to build on this momentum in its second year.

On Sept. 9, the league’s six teams announced their branding. Organizations once named after cities became the Boston Fleet, Minnesota Frost, Montréal Victoire, New York Sirens, Ottawa Charge, and Toronto Sceptres.

Merchandise sales, ticket sales, and media interest have all increased, said Burkett.

The league has also changed some of its venues. Toronto struck an agreement with the Coca-Cola Coliseum to host games in that 8,000-seat arena next to BMO Field and the Canadian National Exhibition. The New York Sirens home games will be played in Newark’s 16,755-seat Prudential Center, home of the NHL’s New Jersey Devils. The Montréal Victoire upsized to the 10,000-seat Place Bell in Laval.

One concern remains. The Boston Fleet are still stranded at the 6,500 seat, hour-from-the-city Tsongas Center.

Hirshfeld believes the financial support of Walter and King allows the league to be built “the right way,” without having to be overly concerned about turning a profit immediately. With no shortage of money, the PWHL is taking time to make sure infrastructure is in place to build a league that will last.

Newfound fans

Without fans, professional sports leagues can’t exist. Sportico, a Los Angeles-based media outlet devoted to the business of sports, reports 44% of NHL revenue in 2023 came from ticket sales. Another 12% came from stadium concessions and parking.

With in-person fan engagement accounting for over half the NHL’s revenue, the importance of the PWHL getting fans into its buildings is clear.

Heidi Van Regan, a Montréal season ticket holder and founder of the P-Dub Fan Club on Facebook, takes pride in introducing people to women’s hockey. Last season, Van Regan used her seven season tickets to bring 59 different people to games. This season, she has 13 season tickets and plans to invite even more new fans.

She doesn’t worry that the people she brings won’t enjoy it. Van Regan has confidence in the PWHL. “Anybody who goes is going to be impressed,” she said. “It’s not just the men’s game with ponytails.”

She predicts the PWHL will have no problem with attendance. She believes people, particularly women who were told “that hockey wasn’t for girls, that hockey was only a boys’ game,” were waiting to support a professional women’s league.

“The audience was there,” she said, “before the league started.”

Growing the game

Ian Kennedy of The Hockey News believes that to build a fanbase, women’s hockey needs to be accessible to everyone.

With YouTube broadcasts, fans don’t have to deal with network blackouts and media can report on every PWHL game remotely. During the season anyone, anywhere, can follow the league.

That said, Kennedy’s biggest concern about the PWHL is its current six month offseason. A break that long could allow interest to wane.

Following June’s entry draft and the start of free agency, there were months of silence from the league. “Sometimes they say no news is good news,” said Kennedy, “but I don’t think in this case that’s the deal.”

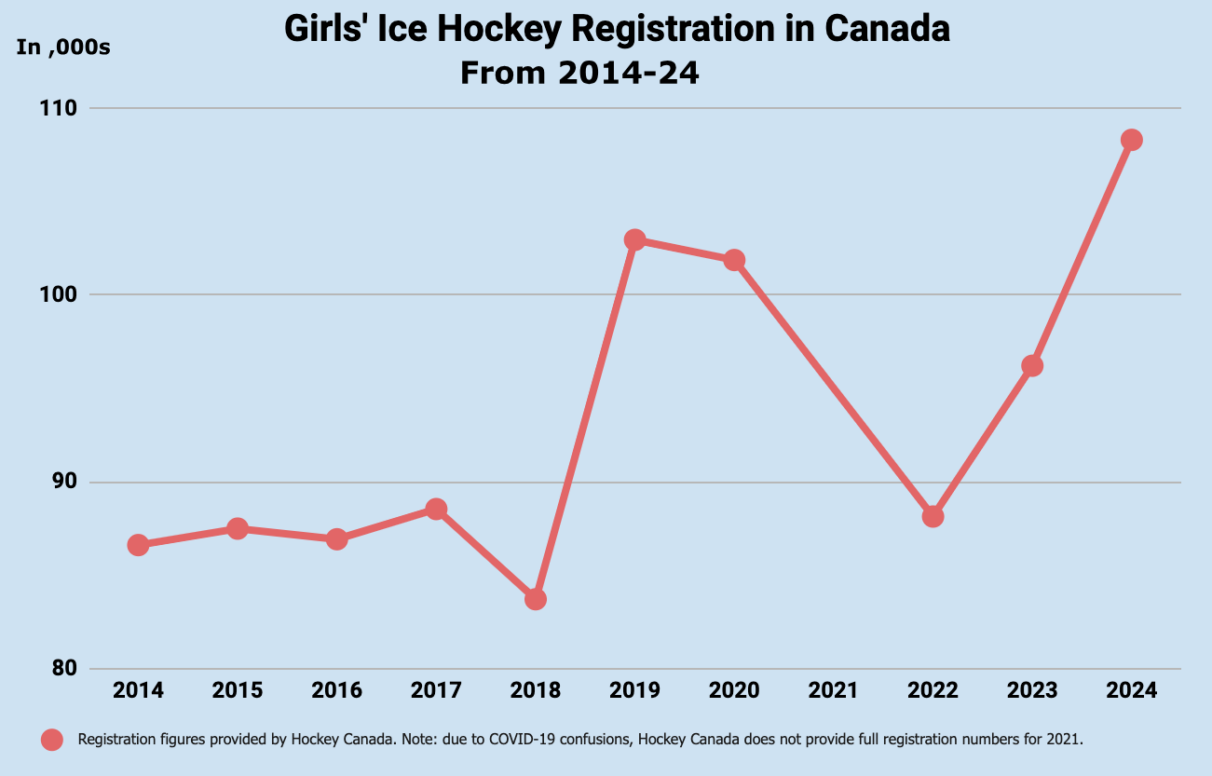

Media attention and community initiatives like youth hockey clinics allow the PWHL to influence the broader hockey world. To see the PWHL’s impact, peek your head in any hockey arena across Canada. More girls are playing hockey than ever before. This year shows a 12.5 per cent jump in registration from 2023, with 108,313 girls playing nationwide.

For the PWHL, presence in the media and community benefits everyone. Creating connections with fans builds excitement beyond novelty, said Hirshfeld. In turn, loyal fan bases can develop.

A long journey

Following Kristin O’Neill’s collegiate career at Cornell, she played with the Professional Women’s Hockey Players Association (PWHPA), a precursor to the PWHL. The PWHPA was a nonprofit that advocated for women’s hockey.

From 2019 to 2023, the PWHPA boycotted existing women’s hockey organizations while holding out for a financially stable, professional league.

“When I joined the PWHPA, there wasn’t really an end in sight,” O’Neill said. “I think for a lot of us that was pretty daunting.” What kept players motivated, she said, was hope – hope that one day a pro league would materialize.

Negotiations with the PWHPA and a buyout of the Premier Hockey Federation were the final moves for Walter and King to form the PWHL. The league that Kristin O’Neill and thousands of other women waited for was becoming a reality.

“It was hard to think we would be where we are now.”

About the author

Connor Parent

Connor Parent graduated this spring with a Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) degree from the University of King’s College.