Kids have ‘so much to give,’ says pollution researcher

How a German marine biologist is teaming up with Halifax schoolchildren to fight plastic pollution

caption

Tim Kiessling delivers a lecture on how citizen science is an integral part of the fight against pollution.How can we cut down on plastic pollution? Conventional wisdom says we should educate adults.

But Tim Kiessling, a post-doctoral researcher from Germany, believes that it should start with children.

“We can enable kids to participate in research — to really value their input — because they are excluded in so many ways,” Kiessling said in an interview.

“They cannot vote. They cannot participate (in so many things). The aim is to get them more involved in everything because they have so much to give.”

Kiessling conducts his studies alongside children and teenagers. He and volunteers from Halifax schools go out to collect litter, sort it and assemble various datasets.

He said most of what his groups gather is plastic.

Kiessling put forth his vision of how citizen scientists are an integral part of the fight against pollution at Dalhousie University’s Kenneth C. Rowe management building on Tuesday.

“When I talked to the schoolkids, I often ask them who do you think is responsible for the plastic pollution? They often say we are a bit, and our parents are because we buy this plastic,” he said.

“You’re only so responsible, because then there are the companies and the government, and the policymakers who are not enacting enough legislation on this.”

“I try to not overburden (the children) with the message that they are responsible, but then they have the responsibility to hold others responsible,” he said.

Kiessling has a PhD in marine biology and has worked alongside a similar program in his native Germany called Plastic Pirates.

Kiessling has only worked with Halifax-area students since September, but he has already involved seven schools.

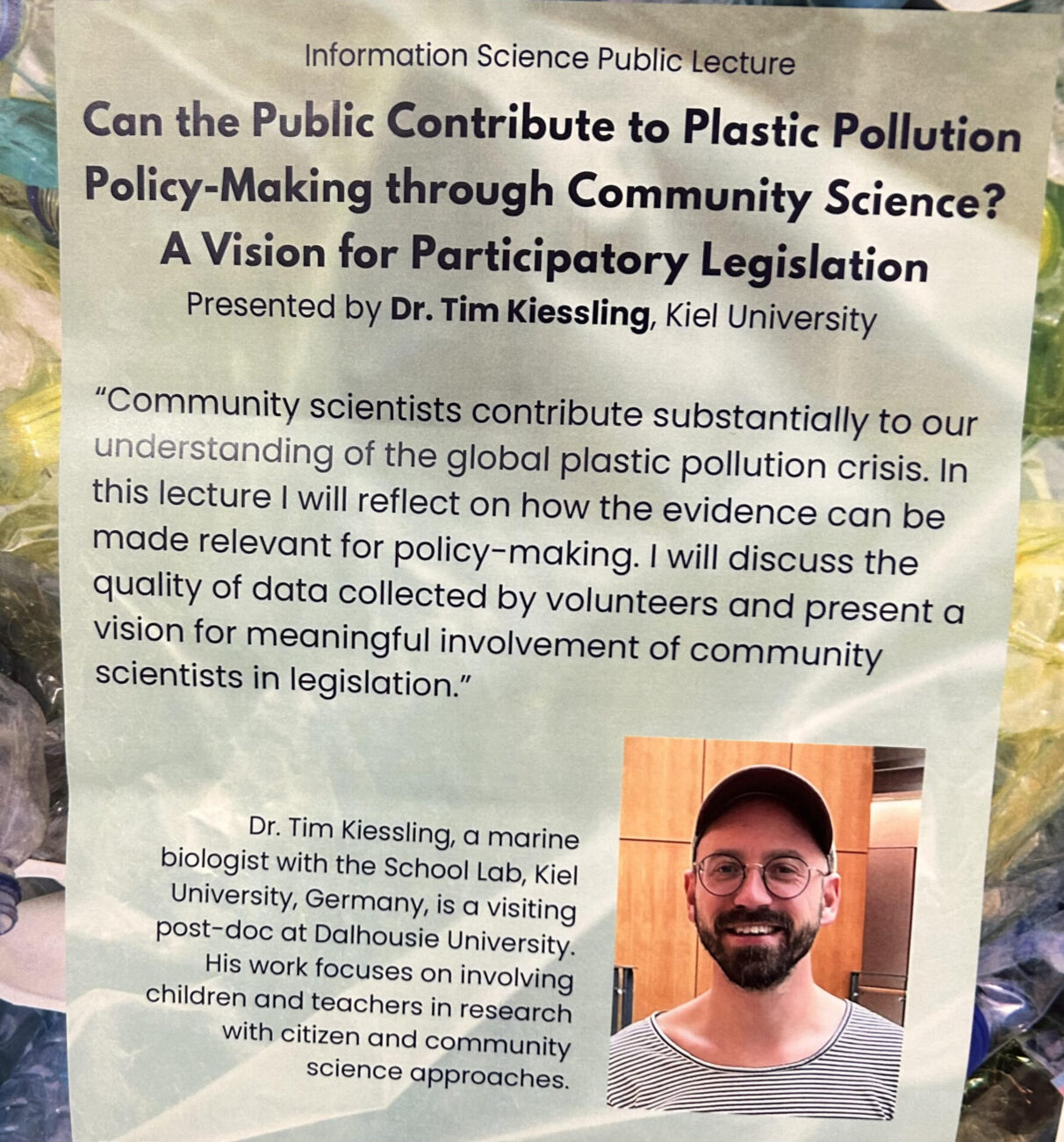

caption

Flyers like this were all over Dalhousie Campus, advertising Kiessling’s speech at the Rowe building.“He has 10 years of extensive experience working with citizen scientists. In this particular case, it’s schoolchildren,” said Dalhousie environmental studies professor Tony Walker.

Walker, who is a colleague of Kiessling’s at Dalhousie, said “my takeaway is that young kids are collecting data which can be used by policymakers to eliminate or reduce plastic pollution.”

“Sometimes it’s the kids who actually tell their parents, tell their grandparents and suddenly members of the public start listening,” said Walker.

Kiessling’s presentation ended with his vision of how citizen science can help inform both researchers and citizens and result in better solutions to the pollution crisis.

Heather Oliveira, who was in the audience, said the lecture “underscores the importance of integrating citizens into scientific research, especially because it’s gonna impact all of us.”

“There are a few barriers we need to face, and we need to figure out how to combat,” she said.

“One of the biggest ones being how do we integrate citizen science into research papers that can be scientifically published,” she said.

Kiessling showed the audience some negative feedback he and his team received following their first attempt at publishing a study with citizen science in an academic journal.

“They had an initial bias against (regular) people participating. I think anyone can participate in research.”

“Citizen science is something that has a lot of potential but still needs a lot of support to get off the ground, especially when it comes to plastic pollution,” said audience member Julia Crowell after the lecture.

“Students were able to really engage with the topic and be able to provide on par quality data,” she said.

Kiessling wanted the audience to above all else see the potential for this kind of research.

“My main message is really consider what young people can do, because they can do a lot, we just have to put them in a position where they can.”

About the author

Jack Sponagle

Jack Sponagle will graduate this spring with a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of King’s College.