The future takes a back seat

caption

Lovelace speaks to young voters at the HMCS King’s Wardroom in the University of King’s College in South End Halifax. Throughout her campaign, Lovelace encouraged groups that are traditionally underrepresented in municipal elections, such as young people and new Canadians, to come out and vote.Halifax has only had a woman mayor once in its 275 years. Who is the latest woman to whom we said no?

Editor's Note

Most of this story was reported and written before Oct. 19, election day.

She’s wearing a bright pink blazer among shades of grey and blue. Pam Lovelace’s signature look stands out onstage in the Westin Hotel’s Commonwealth Ballroom. On both sides of her are men who also want to be the next mayor.

When her opponents speak, she keeps a studied, neutral face. She’s seen how U.S. vice-president Kamala Harris is treated by the press. This has to be about what she says, not how she looks.

Women in politics have to balance being feminine enough that people are comfortable with proving they can lead assertively. Lovelace keeps up a smooth veneer. Reapply neutral lipstick outside the elevator. Study on the way from one event to the next. Make sure hair is doing what it’s supposed to. Make sure never to need notes. She sees this as proof that she knows what she’s talking about – no prompts needed.

She arrives at 9:28 a.m., 32 minutes early. Being punctual is another part of the polish. Her twenty-one-year-old son Callum, in a black blazer and bolo tie, brings her a glass of water. Lovelace’s two children and husband are important supporters; usually at least one of them is at events like this.

On one pink lapel is a beaded red dress pin representing missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. The pin on the other reads PAM LOVELACE FOR MAYOR. The only woman in the race, she comes from a council that had gender parity for the first time ever. Lovelace is an underdog who stands up for the underdog, whether that’s showing women belong in politics or imagining a world class transit system for HRM.

How did she come by this attitude that she carried into municipal politics?

Growing up, Lovelace spoke German. Her father immigrated from West Germany, and was slow to learn English. “That’s what drove me – I’m just realizing this now – that’s what drove me to make sure I was always articulate and consistent,” she said, the adjectives enunciated, precise. “And that I could orate.”

At first glance, Lovelace’s white, suburban mom image might not prompt people to look much further. They might assume her life has been gemütlich (agreeably pleasant) throughout.

Yet Lovelace is no stranger to hard work. She got her first job at 13. “We had no money,” she said. “My mom was just like, ‘No. You want it? You work for it’.”

To make tips at the Old Orchard Inn in Wolfville, she learned how to connect with people in the time it takes to serve a coffee. At 16 she quit school and left home to work full-time in catering at Acadia University.

While her friends were graduating high school and starting university without her, she decided to move to Montreal. “I was 16, 17 years old. I didn’t know anything,” she said. “Other than how to work.”

She skirted human trafficking in Montreal (thanks to a friend who bought her a plane ticket back to Nova Scotia) and ended up homeless in Halifax. “I felt like I was always in this hamster wheel of trying to make ends meet, and trying to figure things out. And then, I ended up getting into Mount St. Vincent University.”

At the Mount she earned a Bachelor of Arts in English, a minor in German and a Business certificate.

caption

Mayoral candidates speak to an audience at the Delmore “Buddy” Daye Learning Institute in Halifax’s North End on 12 Oct. 2024. The event focused on the needs of Black and new Canadians.Trials of a councillor

Lovelace was councillor for Hammonds Plains-St. Margaret’s from 2020-24. The biggest trial she faced was in 2023, when wildfires tore through her district. “That whole summer,” she said, “was a nightmare.”

People wanted answers while waiting to find out if their homes were on fire. But as councillor, while you’re accessible to people in your community, you don’t have a direct line to Big Government.

Lovelace’s own home had to be evacuated, so she stayed with an old friend during the crisis. Jennifer O’Neil has known her for more than twenty years. “She’s a great bestie,” said O’Neil. “She’s the kind of friend that will tell you straight up.”

“Her phone didn’t stop, and people were yelling and screaming.”

When a state of emergency was declared, the province took the reins; communications with councillors was not a priority. Lovelace couldn’t give those she represented the answers they wanted.

Lisa Blackburn was District 14’s councillor at the time. She sat next to Lovelace for four years in City Hall’s Council Chamber. “Those were times where I sort of gave her hand a squeeze, or rubbed her back while she was speaking.”

Lovelace had started work on emergency exits for suburban communities in 2021. But one of the worst hit neighbourhoods, Westwood Hills, is still waiting for a back exit. It’s stuck in a hamster wheel of council motions and staff reports.

caption

Lovelace speaks to men at the Sabee Muslim Youth & Community Centre in Bedford on 16 Oct. 2024. She related to the immigrant experience of speaking a native language at home and the struggles children face when that language isn’t embraced at school.

caption

Lovelace speaks to two women after a candidate’s debate at Saint Mary’s University in the South End of Halifax, on 10 Oct. 2024. Five of the 16 candidates were invited to this debate.Speed of light rail

Wanting to speed up change motivated Lovelace to run for mayor instead of trying for the same council seat again. She juggled councillorship, family life and the mayoral race. Light rail transit was a flagship of a forward-thinking campaign. So why did she finish third?

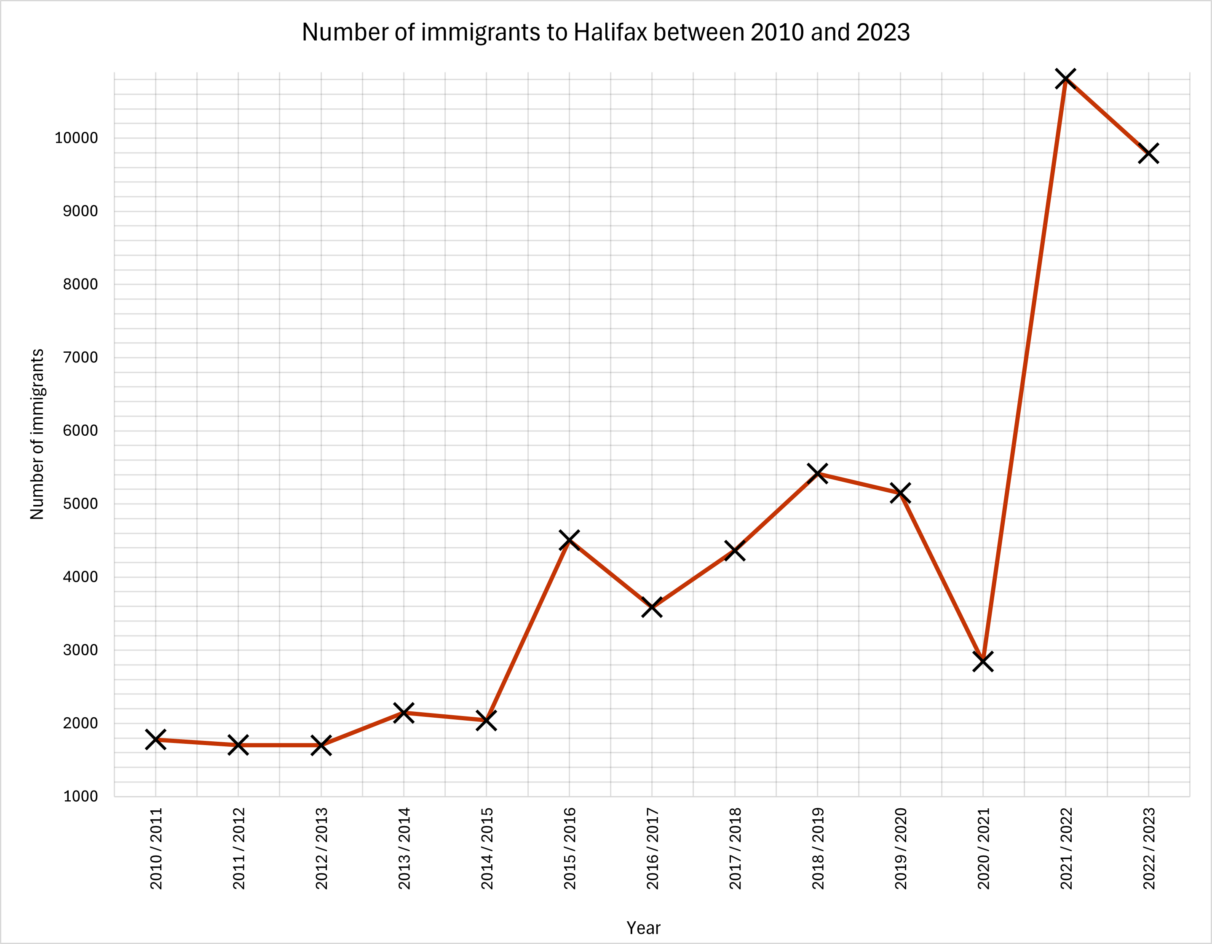

In 2021, more than 10,000 people came to the municipality from abroad – more than one person every hour. Halifax ranked among the top ten Canadian cities by population size only in the first 40 years after Confederation. Since then, it’s been growing at a slower rate, despite being the biggest city in the Atlantic provinces. Until now.

The Atlantic provinces are “just not quite psychologically prepared for what it might mean if (growth) actually came,” said Dr. Zack Taylor of Western University in London, Ont. Taylor is an investigator at the Western-based Local Democracy Project, which researches Canadian municipal politics. “I’ve spent the last almost 20 years in Ontario,” he said, and “you just get used to steamroller growth.”

Standstill Halifax traffic that locks understated Porsches, rusting low-slung Hondas and transport trucks bumper-to-bumper(-to-bumper) is the clearest indicator that things are changing. It would be hard to believe if the infrastructure wasn’t buckling, but just ten years ago worries of an aging population and a shrinking economy lapped at Nova Scotia’s shores.

Before the campaign, Lovelace said how important it is not to once again become “a city of grandparents.” Her plans to speed up light rapid transit indicated an intent to push HRM into the future. Perhaps Halifax isn’t ready for that push.

Ellen Pottie, who met Lovelace during lunch at Spencer House Senior Centre, planned to vote for Andy Fillmore. “Better the devil you know,” she said, “than the devil you don’t.”

Lovelace steadfastly talked about the need for a 50-year plan. At a retirement home in Clayton Park, she told seniors in a beige breakfast lounge about goals that would go beyond their lifetime. But the mask she wore facing off with opponents came down in conversations with voters. She became more personable.

What’s true about Lovelace is that, throughout the race, she did her due diligence, thoroughly. She always started with “Hi, I’m Pam,” even if she had just been on stage. She’d shake hands with constituents and then listen. She would ask questions. And then she took down phone numbers, to follow up on specific concerns.

caption

Lovelace speaks to seniors at Parkland Retirement Living in Clayton Park on 12 Oct. 2024. She remained adamant about the need to plan for the next generation despite the older demographic of voters she spoke to.What now?

Lovelace’s campaign was founded on the support of volunteers. Candidates spend thousands on signs alone, and hundreds of hours travelling to talk to voters. Andy Fillmore, the eventual winner, and Waye Mason, another councillor, were her two main competitors. Compared to them, Lovelace didn’t have much in the way of funds. She raised less than 10 per cent of the $300,000 maximum fundraising allowed for a mayoral campaign. Despite this she won 16 percent of the votes, almost 20,000.

If Justin Trudeau’s Liberals weren’t tanking, Fillmore might still be an MP. While he smiled down from bus shelters, Pam’s husband, Dave Lovelace, planned to weigh down lawn signs on Thanksgiving weekend in preparation for windy weather. He remembered from four years ago that civic elections are during hurricane season.

Now that the race is over, Lovelace is going to keep teaching local government at Dalhousie. She’s also thought about looking for work with the Nova Scotia Co-operative Council, to build affordable housing. She wants to carve out space for her kids and other young people in an increasingly inhospitable economy.

With a short, wry chuckle she said, “I’m gonna dust myself off. I’m going to move forward with being me, and continuing to do the work that I do to create change.”

caption

Lovelace speaks to young voters at the HMCS King’s Wardroom in the University of King’s College in South End Halifax. Throughout her campaign, Lovelace encouraged groups that are traditionally underrepresented in municipal elections, such as young people and new Canadians, to come out and vote.About the author

A. Zwissler

Antonia Zwissler, who came to Halifax from Lima, Peru, will graduate this spring with a Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) degree from the University...