Castles made of sand

caption

Ralph Wardrope’s cottage and trailer sit near the eroding shoreline in Bass River, N.S., where steep banks show signs of ongoing coastal erosion.Coastal property owners in Atlantic Canada are losing land to rising sea levels and record storm surges.

Driving west along Nova Scotia’s Trunk 2 on the north shore of Cobequid Bay from Truro to Parrsboro is a trip through time.

Shrinking communities line the shore where the relentless tides of the Bay of Fundy – the highest in the world – have carved a geologic record into cliff faces along the Minas Basin and Cobequid Bay as they roar inland every day, leaving briny rivers and deep lakes with wide mudflats and sand bars as tribute to the province for the land it’s sacrificed.

Bass River, N.S., is a village located almost halfway between Truro and Parrsboro on the banks of the Cobequid.Once known for shipbuilding, furniture manufacturing, timber exports, silica mining and, of course, fishing, the village boasted a bank and a hotel in the early 20th century. The Dominion Chair Company in Bass River employed between 40 and 70 people at any given time from its opening in the late 19th century until it closed in February 1989 after its sixth fire.

Wendy Cox is a member of the Bass River Heritage Museum’s board. She runs the Dominion Chair General Store out of the company’s former headquarters. Her family summered at their cottage in Bass River every year before moving there from Truro, N.S., in 1980. She said the community has struggled since the loss of the chair factory.

“Everybody has to go out of the community to find work,” Cox said. “We’ve lost lumber businesses. We’ve lost community stores. We’ve lost two garages, like service stations. One of our schools was shut down.”

The general store endures in part because the community still attracts cottage owners and anglers who buy frozen herring and squid to use as bait when the striped bass are running in the bay. Cox said business gets a huge bump in the summer.

“The population pretty much doubles on our shore,” she said.

caption

A sign for Dominion Chair stands in front of the former furniture factory site in Bass River, N.S., with a new bridge under construction in the background.Many residents left with the manufacturing, but cottage owners aren’t just concerned about their neighbours who are leaving. They’re worried about the land they’re losing.

Ralph Wardrope’s family has owned property in Bass River for almost 50 years. In that time, the tides carried away huge chunks of the sandy bank at the edge of his land.

“It’s a further walk out to the water at low tide,” Wardrope said. “There’s a hell of a lot of land lost up and down the coast.”

Wardrope’s summer cottage sits on a quarter-acre of land with about 30 metres of steep bank on the south side that drops about four to six metres down to the beach. He bought the property from his father in 1997, who purchased it in 1976.

“I’m going to say we lost close to 120, maybe 130 feet from when dad first purchased the cottage,” Wardrope said. “I’m paying property tax for land that’s at the bottom of the Cobequid Bay.”

It’s the same thing at Cox’s cottage.

“We’ve put in new breakwaters in the last 30 years,” Cox said. “We’ve lost three roads.”

caption

Ralph Wardrope, left, sits beside his son Tim Wardrope outside Ralph’s home in Milford, N.S.

caption

A view of the Cobequid Bay from between the cabin and trailer, at Ralph Wardrope’s property in Bass River, N.S., shows the shoreline and the Cobequid Bay beyond.Erosion is a healthy process that is balanced by accretion – the process that feeds beaches and carries sediment to marshlands – but recent data is concerning for coastal settlement, according to the director of the TransCoastal Adaptation Centre in Halifax.

“Internationally, you start to see an increase in rates of erosion around the year 2000, and we have seen acceleration in sea level rise,” said Danika van Proosdij. “More water at the coast means bigger waves. For erosion processes that are driven by bigger waves, if you have deeper water closer to the coast, you’re going to get more erosion, because there’s more energy.”

Between 1984 and 2015, the Earth lost almost 28,000 square kilometres of land to erosion – almost twice as much land as it added through accretion – according to a study from a research centre that advises the European Union. Human activity and construction are the primary drivers of land loss, the study’s authors concluded. Building coastal infrastructure alters sediment and destroys coastal ecosystems, the study said.

Tim Webster is the lead research scientist with the applied geomatics research group at the Nova Scotia Community College (NSCC) in Middleton, N.S. He said there are places where the coast has grown, but it’s mostly receded through erosion.

“Very typical in Nova Scotia as well as the rest of the Maritimes, those rates turn out to be about … 30 centimetres a year on average,” Webster said.

Wardrope said in his experience, it’s not the average you have to worry about.

“There was eight to 10 feet of ground and then there was the road. One November the whole thing went,” he said.

I grew up with the Wardropes, fishing the bay for stripers with Ralph’s son, Tim, dragging our chairs up the beach to escape the incoming tide. In 2009, before I moved away, the road to the cottage was on the south side, between the Wardrope property and the beach. When I moved back in 2017, we took the new road on the north side of the cottage to go fishing.

In eight years, the old road washed away.

It was a before-and-after snapshot more dramatic than a weight-loss marketing campaign, and Wardrope said it happened in a single season.

“I think we lost about 30 feet of bank that year,” he said.

If it weren’t for the generosity of his neighbours, who let him use their private road, Wardrope said he wouldn’t have access to his cottage at all. He said he’s got about six metres before the Cobequid Bay reaches his septic tank.

“I’m not sure what I’ll do after that,” he said.

caption

Large boulders line the shore outside Ralph Wardrope’s cottage in Bass River, N.S., part of an attempt to harden the coast against erosion.Rising tides and black swans

Coastal erosion isn’t as vainglorious as its catastrophic siblings. Tsunamis, storms and floods rip communities up by their foundations and leave scenes of destruction splashed across front pages.

Erosion is a slow process – most of the time.

Wardrope’s parents rented a cottage on Cobequid Bay before they bought theirs, so he’s been watching the tides for 62 years. A short time geologically – but long enough to see the writing on the wall.

“I suppose in hindsight I’m naïve,” Wardrope said. “When Dad built the new cottage, it should have clicked in.”

It’s been 30 years sincethe Wardropes moved the old cottage and built a new one to escape the incoming tide.

“Not even a lifetime,” Wardrope said.

It’s hard to know where coastal erosion ends and flooding begins in the overlapping classification of climate disasters. Still, with 13,000 kilometres of shoreline, Nova Scotia could prove to be ground zero for an unwelcome blend of seawater intrusion and collapsing landmass.

The Bay of Fundy – which feeds the Chignecto Bay – is another big variable.

Every year, more than 300,000 tourists visit the Fundy National Park in southern New Brunswick to see the impact of the world’s highest tides. The tidal range can reach more than 16 metres between high and low tide in some places because the geography funnels more than 640 billion tons of water into the Bay – more than 16 times the volume of all the rivers on earth combined – force-feeding the rivers and tributaries of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick like foie gras.

The full power of the funnelling effect is on display where the Cobequid Bay flows into the Shubenacadie River in Maitland, N.S. The incoming tidal force on the Shubenacadie is so great that it generates a tidal bore – a wall of water that charges upriver ahead of the incoming tide and swallows sandbars that generate standing rapids and whirlpools.

I worked the tidal bore as a rafting guide in the early 2000s. During the slow, lazy trip upriver at low tide, there is evidence of erosion carved into the limestone cliffs and steep mud banks, but it’s hard to believe the placid waters created such spectacular geography until the tide turns.

The river jumps between six and 10 metres in two hours with every incoming tide, tearing up trees, reshaping the landscape and offering one hell of a ride to intrepid tourists craving a tidal adventure who don’t mind getting wet.

The collapsing chunks of bank giving way under the incoming tide make erosion visible in real-time.

This is the process Wardrope describes outside his cottage: slow, steady and unnoticeable to the seasonal tourist until it all collapses like a Jenga tower in a big November storm or some other black-swan weather event.

caption

The eroded pillars of an old rail bridge spanning the muddy waters of the Shubenacadie River near Maitland, N.S., are pictured.Through the hourglass

Human beings have lived with the risks of a coastal lifestyle throughout history. Alexandria, Egypt, was founded in 331 B.C. It is one of the largest cities on the Mediterranean Sea with a population of over 5.2 million. A study published by Cambridge in 2023 showed 2.15 billion people live in the near-coastal zone and 898 million in the low-elevation coastal zone globally, but there is evidence that our relationship with the sea is becoming less predictable and riskier, even for historically stable regions settled for their coastal resources.

Building collapses have “accelerated from approximately one per year to an alarming 40 per year over the past decade,” in Alexandria, according to a report from the University of Southern California, suggesting 2300 years of coastal stability is threatened in the region.

In California, some areas are sinking faster than sea levels are rising, according to a NASA-led study that used satellite radar images between 2015 and 2023 to measure more than 1,000 kilometres of coast. The San Francisco Bay area is subsiding at a rate of more than 10 millimetres per year, the study showed.

The archipelagic nation of Indonesia lost 668.64 kilometres of coastline between 2016 and 2021, said a study published in 2024.

Elsewhere in Nova Scotia, the government is preparing to move 500 metres of the Lawrencetown Road – Highway 207 along the province’s eastern shore – up to 40 metres back from the coast in response to the increased threat from storm surges.

Climate change skeptics argue sea levels and atmospheric compositions have always been in flux, but rapid changes in recent decades mean the results – everywhere from Alexandria to San Francisco to Bass River – could be unprecedented.

To understand the historical erosion rate and develop a predictive model, Tim Webster and his team at NSCC use aerial photography.

“We have photos here on the Maritimes that go back to probably the mid-30s,” Webster said. “We can take those photos, rectify them into a map, and then interpret where the coastline is. Often, we would use the top of the cliff or the top of the bank, things like that. And what that allows us to do is to look at how that position of the coastline has changed over time and how it’s receded.”

Webster said the average of 30 centimetres a year is deceiving. His observations are consistent with Wardrope’s experience.

“It’s really an episodic process,” Webster said. “You could go years without any big storms and have very little erosion. And then it takes one big storm and, all of a sudden, maybe you’ve eroded a couple of metres.”

Webster and his team use drones to get what he calls “full three-dimensional coverage” of the coastal area they’re studying. They measure storm magnitudes and weather information to understand the drivers of erosion.

“Now, not only can we calculate the recession, the horizontal movement of that top of bank, we can actually calculate the volume of material lost,” Webster said.

Post-tropical storm Fiona hit Prince Edward Island and the rest of the Maritimes in September of 2022 and delivered an unprecedented storm surge.

“We’ve been monitoring the north shore of the province with instruments since about 2010,” Webster said. “We have tide gauge records that go beyond that, but that by far was the highest storm surge we’ve ever recorded.”

Webster said that warming oceans are driving hurricanes and sustaining their strength in Northern latitudes.

“Those two things contribute to the impact of erosion from storm events and coastal flooding,” he said.

“When Hurricane Fiona came through, or I guess we call it post-tropical storm Fiona, but for the shortness and the impact, it was still hurricane force winds,” Webster said. “You know, the water off Nova Scotia was still 20 degrees Celsius in September.”

According to the Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC), Fiona was the most expensive extreme weather event in the history of Atlantic Canada, with an estimated cost of $660 million in insured damage.

Four people died when the storm hit Atlantic Canada in September 2022, but it might have been worse if not for evacuation efforts. The storm washed away at least 20 homes, primarily in Port Aux Basques, N.L., said the IBC in its report. Homes and buildings were also destroyed in Burgeo, Burnt Islands and Fox Roost.

Erosion was most destructive in Prince Edward Island where at least 60 roads and bridges and six schools were damaged during Fiona, said a report from NOAA. The storm generated waves more than eight metres in height and “resulted in erosion of mainland and barrier sandy beach systems including about 40 km of shoreline managed by Prince Edward Island National Park,” according to a study conducted by researchers from the Maritimes and around the world.

Cut off

The Northumberland Strait is the narrow body of water that separates Prince Edward Island from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick by as little as 13 kilometres at its most narrow and 43 kilometres at its widest.

The Northumberland coast of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick is one of the most vulnerable regions in the Maritimes, said van Proosdij.

“We’ve got high rates of erosion occurring in areas that are basically exposed to large swells and waves of the Atlantic Ocean,” van Proosdij said.

The Confederation Bridge that connects Prince Edward Island to New Brunswick lies almost directly north of Bass River, on the other side of the Chignecto Isthmus – the 24-kilometre wide land bridge connecting Nova Scotia to New Brunswick, the Canadian mainland and the rest of the continent.

Close to $100 million in trade crosses the Chignecto Isthmus every day – 35 billion a year, according to the Nova Scotia government. As sea levels rise, there is increased concern that the isthmus will flood and erode until Nova Scotia is an island with its supply arteries severed.

NOAA was correct when it predicted a busier hurricane season for 2024.

“Talk to somebody from Florida, they would probably say, ‘Yeah, most definitely it was,’ because it seemed like they were getting hit by hurricanes there, you know, on a weekly basis or biweekly basis,” said Webster. “Luckily, none really impacted us in Nova Scotia all that much.”

NOAA predicts more frequent hurricanes ahead for 2025.

caption

Exposed septic pipes jut from the eroding bank at Ralph Wardrope’s cottage in Bass River, N.S.Van Proosdij said high bluffs, cliffs and soft banks that are stripped of vegetation – like those found in many spots along the banks of the isthmus – come down fast when they are weakened by the tides.

“If we have these heavy rainfall events that happen in a short period of time, we’re going to get a lot of overland flow,” van Proosdij said. “And so that drives erosion from the top, and we’ve got waves driving erosion from the bottom.”

It’s an apt description of the Chignecto Isthmus, trapped between the tidal force of the Bay of Fundy on the south and the North Atlantic waves pounding the Northumberland coast.

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick reached an agreement with the federal government to protect the Chignecto Isthmus in March after a long debate over who would pay for a proposed project with an estimated budget of $650 million. Under the 10-year funding agreement, the provinces pay $162.5 million, 25 per cent each, with the federal government paying the remaining half through the Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund.

Nova Scotia is awaiting a ruling on a constitutional reference to the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal to determine if the federal government is responsible for the cost to protect the isthmus based on the Constitution Act of 1867. In a 2024 statement, Premier Tim Houston said it was remarkable that the federal government had not assumed full responsibility. He said the isthmus was vulnerable to one episodic weather event severe enough to have “cascading ramifications.”

“This infrastructure is truly of national importance,” Houston said. He cited the Champlain Bridge project in Montreal, where the government assumed 100 per cent of the $4.2 billion cost, as precedent.

Nova Scotia maintains the federal government is responsible for the critical land corridor and will maintain its reference to the court, but “it is in everyone’s best interest to strengthen and protect this interprovincial trade corridor as soon as possible.”

Falling into the sea

The town of Walton, N.S., is further out to sea than Bass River, on the southern coast of the Minas Basin, the body of water the Bay of Fundy flows through on its way to Cobequid Bay and the Wardropes’ cottage.

In 2024, the Municipality of Walton did something the folks in Bass River did twice before: they moved their lighthouse. It’s so common to move lighthouses in Nova Scotia that the Nova Scotia Lighthouse Preservation Society has guidelines published on its website.

The Walton Lighthouse was built in 1873 for $620, according to the Nova Scotia Lighthouse Preservation Society. The town spent $92,000 to move the lighthouse after a 2022 coastal vulnerability and projected erosion study that digitized coastlines from the Shubenacadie River to the Walton River showed average shoreline loss of about 1.2 metres per year in some areas from 1973 to 2019.

The study projected coastline positions for 2050 and 2100. The images show historic coastal regions, homes, businesses and highways could all be resting on sand passing through an hourglass beneath their foundations.

There is perhaps no better metaphor for the erosion crisis than the lighthouse. The historical heralds that warned sailors on their approach to land now serve as a warning system for another kind of marine disaster.

In the case of Walton, the lighthouse also highlights issues surrounding coastal protection, access and ownership in Nova Scotia.

In 2024, Nicolas Winkler and Hannah Harrison launched the Right of Way podcast to examine the issues of coastal access and protection in Nova Scotia.

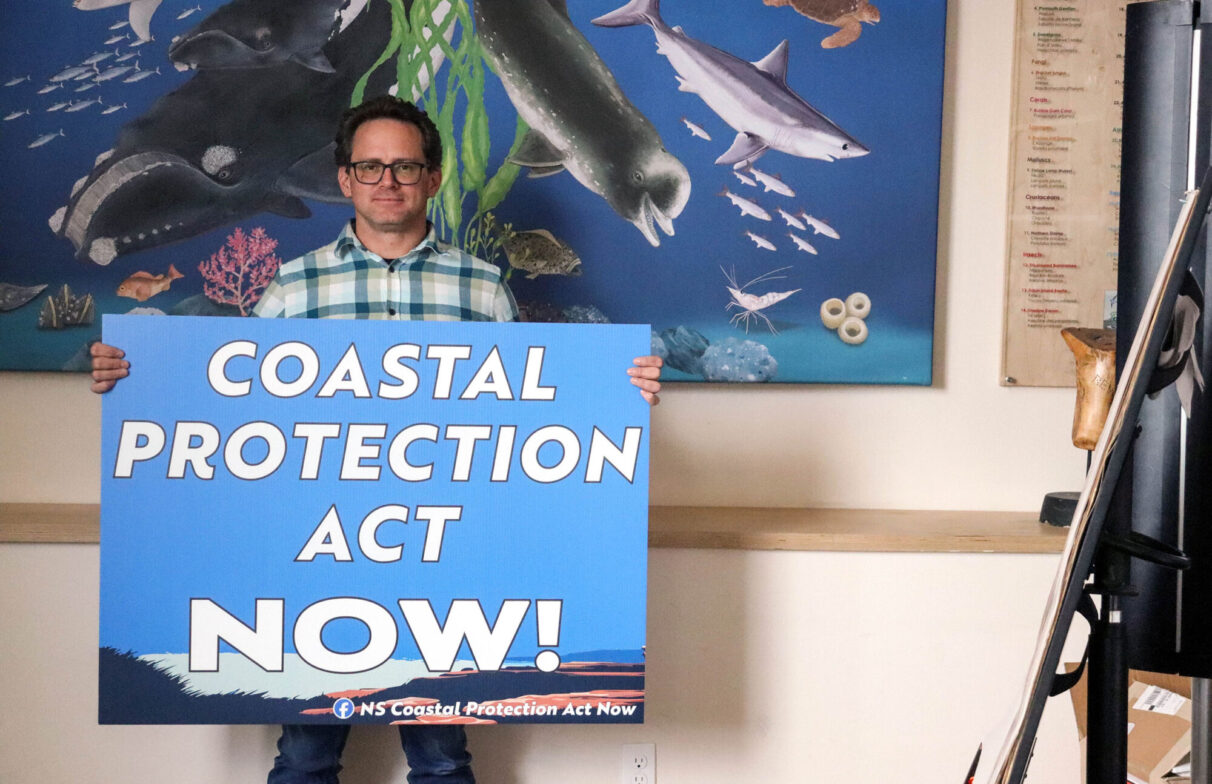

caption

Nicolas Winkler holds a sign calling for the proclamation of Nova Scotia’s Coastal Protection Act during at the Ecology Action Centre in Halifax, N.S.Winkler is the coastal adaptation coordinator at the Ecology Action Centre (EAC), a member-based environmental charity in Halifax, N.S. The focus of his work, he said, is coastal management legislation, particularly the Coastal Protection Act (CPA) – a short-lived piece of legislation. The Houston government scrapped the law in February 2024, even though it passed with all-party support less than five years earlier.

“It seems that every time we get close to sort of getting there, it falters,” Winkler said. “It’s not going away. It’s a problem that we have not been able to effectively deal with.”

When the province declared it would not proclaim the CPA in 2024, it released the Future of Nova Scotia’s Coastline: The plan to protect people, homes and nature from climate change along our coast in its place. The plan places more responsibility for coastal management in the hands of municipalities and private landowners.

In April of 2024, the public-interest legal advocacy group East Coast Environmental Law – which fought for the CPA on behalf of Winkler’s associates and the public – published a post comparing the CPA to the Houston government’s plan.

The firm cites the provincial government’s 2009 State of Nova Scotia’s Coast Report that found “multiple pieces of legislation dealing with coastal resources are a barrier to achieving an integrated plan for coastal management and sustainable development.” The law firm’s comparison alleged that the coastal plan that replaced the CPA “is inadequate and fails to incorporate best practices for effective coastal management.”

Winkler said the plan places decisions about the province’s future in the hands of a minority of landowners. He said that, however Nova Scotia manages the coast, it needs to be a matter of public policy.

The 2009 report said 86 per cent of Nova Scotia’s coastline is privately owned.

In April, the province announced new resources and funding for coastal communities and property owners that included examples of municipal land-use planning bylaws to regulate coastal development.

“Municipal leadership and regulatory oversight are key as municipalities have jurisdiction for zoning, land-use planning and buildings permits,” said Timothy Halman, minister of environment and climate change.

The province will spend $1 million over three years to help municipalities adopt and customize bylaws to their needs and almost $350,000 to create policy and sustainability analyst positions, said the release.

Winkler said it doesn’t make ecological or financial sense to divide coastal management piecemeal among owners and municipalities with different capacities. He said provincial legislation would act like a building code for the coast to protect the landscape, developers and critical ecosystems.

“Any other jurisdiction in the world that is looking at coastal management, they are taking a comprehensive approach to their coastlines,” Winkler said.

After a lifetime on the bay, Ralph Wardrope agrees.

“We’re supposed to be intelligent people,” Wardrope said. “You should be able to look at something and say, given what’s going on right now, it’s not wise to develop.”

caption

An aerial view shows cottages scattered among the trees along the shoreline in Bass River, N.S., with piles of boulders spread across the beach – all that remains of past efforts to halt the bank’s erosion.The breakwater business

If you’re Joseph MacDonald, coastal erosion is good for business. His company raises and transports homes and other structures across southeastern New Brunswick.

McDonald said moving buildings requires permits from the province, the municipality and, if the move requires road closures, the department of transportation. He said the process costs thousands of dollars.

“We had a boom year,” McDonald said. “That was about two years ago now that the Northumberland Strait here flooded a bunch of cottages.”

McDonald said he’s moved propane tanks, gravesites and covered bridges – all infrastructure that needed to be saved – but moving isn’t the first response from property owners who want to keep their view. Some people are willing to do whatever it takes to keep a family cottage in its place.

Hardening, otherwise known as grey infrastructure or armouring, is part of highway, railway, building and shoreline developments that defend against erosion, said a 2024 study measuring the effect of hardening on the world’s beaches. Grey infrastructure includes seawalls built from stone and concrete to protect private land.

The study showed 33 per cent of the world’s sandy coastline is hardened, and concluded that those coasts are “losing the natural adaptability to accommodate future sea level rise and is therefore more prone to experience beach loss as the shoreline retreats.”

“There’s a concern around shoreline hardening, which is really destructive to coastal environments,” Winkler said.

It also deflects wave energy to neighbouring properties, Winkler said. “This encourages the neighbours to harden their shoreline. You see that in jurisdictions around the world. Somebody starts hardening and it kind of becomes this domino effect.”

Winkler said even with the push for nature-based solutions — using trees, plants and other natural techniques to protect properties from erosion, rising sea levels and flooding — regulations still make it easier for private owners and businesses to harden their shores.

Pieter Webbink is an engineer and the former owner of Eagle Beach Contractors in the Halifax area. He said seawalls can cost tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars, depending on the size and the materials.

“If it’s done well and you size the rocks appropriately, that type of repair should be the end of it,” Webbink said.

Winkler said hardening a shoreline with rocks helps temporarily but does a bad job in severe storms and requires constant upkeep and maintenance.

Wardrope’s family started dumping combinations of boulders and concrete blocks over the bank in the early ‘90s. He’s lost count of how many loads they dropped. All that remains of their efforts today are squat piles of boulders and concrete slabs on the beach, 20 metres offshore at low tide. The waves eroded straight through.

“We used to have wonderful sandy beaches,” said Wendy Cox. “Now we have boulders.”

Van Proosdij said the traditional way of reinforcing the coast is changing.

“We’ve really seen a shift in dynamics and openness to more working with nature rather than against it,” van Proosdij said. She said nature-based solutions are gaining popularity with the Insurance Bureau of Canada and engineering associations.

“We’re preserving the existing natural environment, and that’s really the number one,” van Proosdij said. “Then we can also engineer and construct, build out, if you will, like a living shoreline, such as Mahone Bay to provide that buffer.”

The Living Shoreline in Mahone Bay uses natural materials to reduce shoreline erosion. It consists of three main components:

- rock sill: hard infrastructure runs along the shore to provide stability

- tidal wetland: shallow slope comprised of plants that survive flooding, reduce wave energy and stabilize the sandy base

- vegetated bank: graded area planted with native shrubs that protect the bank.

The Nova Scotia Environmental Network said more rigid elements – such as rock sills and hybrid solutions – may be necessary in “higher wave energy settings.”

The complex nature of the problem will require a combination of solutions, said van Proosdij.

“In areas where we have the really tall cliffs and high rates of erosion, a lot of energy, it’s going to be very challenging for a straight nature-based solution to work.”

It isn’t just cottage country that’s at stake. Nova Scotia was settled because of its coastal resources and depends on them to this day.

According to Tourism Nova Scotia, no matter where you are in the province, “you’re never more than 67 kilometres from the water.”The EAC said approximately 70 per cent of Nova Scotia’s population live in coastal communities and approximately one-fifth of the economy “is supported by coastal and marine industries.”

In the 1970s, climate disasters accounted for US$183.9 billion in global losses, according to a report by the World Meteorological Organization. From 2010 to 2019, that increased by more than 800 per cent to US$1.476 trillion. The report showed losses resulting from storms and floods were the fastest-growing categories.

Erosion doesn’t arrive like a tsunami. You need a lifetime to see it, but there are crescendos that arrive with waves inflated by more frequent and intense storms.

The reality leaves Nova Scotians asking the big questions communities like Walton are forced to ask when they move their lighthouses. The questions Pacific Islanders and lowland farmers are asking themselves as the sea encroaches on their homes. Questions about their coastal identity and lifestyle.

“We’ve already lost so much in Bass River,” said Cox.

After watching the coast for 62 years, Wardrope said it might be time for a change. The data shows it might not be a matter of choice.

“Might look great, might have beautiful views, might sell for millions of bucks. But it’s stupid because, you know, through the years, this land is going to be gone.”

caption

Two wooden chairs face the Cobequid Bay outside Ralph Wardrope’s cottage in Bass River, N.S.Editor's Note

Abridged versions of "Castles made of sand" were previously published by the National Observer and Saltscapes magazine.

About the author

Jeremy Hull

Jeremy Hull works for CBC. He's published in magazines throughout the Maritimes. He's happiest when writing about jiu-jitsu or fly fishing. Jeremy...

Leave a Reply