health care

A frail system

How Nova Scotia seniors are not getting the mental health services they need

In the middle of the night on Nov. 11, 2016, Janice Fraser heard a loud thud, a thud so loud she was woken from sleep.

After hearing the noise, Fraser got of bed to check on her then 85-year-old mother, Helen. Fraser had been staying at Helen’s house in Lower Sackville to help her out after she had been diagnosed with lymphoma.

Upon entering Helen’s room, Fraser found her lying on the floor, writhing in pain. Helen said her head hurt, so Fraser went to the drugstore at 7:00 a.m. to buy a neck pillow.

It never occurred to Fraser her mother had broken her neck.

It wasn’t until later that afternoon, after a friend suggested Helen could have internal bleeding due to her age, that Fraser called an ambulance

Doctors confirmed Helen’s neck was broken.

“I thought I was going to pass out,” Fraser said.

Fraser and her brothers, who were also spending extra time with their mother, expected Helen to stay in the hospital until she fully recovered, as she would need to wear a neck brace.

But an hour after hearing the diagnosis, Helen was sent home. She had caught a life-threatening infection when she was at a hospital for chemotherapy, so Fraser thought, perhaps, staying at home was better.

Helen only lasted two days at home.

“The daily routine was awful,” Fraser said. “Mom was in constant pain.”

caption

Helen Fraser, in November 2016, shortly after breaking her neck.Fraser took Helen to the Cobequid Community Health Centre where staff tried to find a bed for her. They tried Musquodobit Valley, Hants Community Hospital and the QEII emergency department in Halifax, but nothing was available, so Helen was sent home again.

Fraser then asked her niece, who lives in Moncton, for help. Her niece was able to take on around-the-clock care, as necessary. Together, they found a hospital bed for Helen.

The bed didn’t solve the problem; Helen was still in pain.

Fraser and her brothers took Helen to Dartmouth General and refused to take her home again. It was there Fraser learned the neck brace her mother was wearing didn’t fit her properly. Helen stayed in Dartmouth for a month and a half before being transferred to the Victoria General Hospital in Halifax where she would transition to a nursing home.

For Fraser, that transition couldn’t come quickly enough.

“(Victoria General) is just dirty, the water is not good, lots of people roaming around,” she said. “It was just not a nice place.”

Fraser wanted her mother to stay in a nursing home in Lower Sackville so she could be close, but the only bed available was at Northwood in Halifax. Helen moved to Northwood in February 2017.

Even though Helen is doing well at the nursing home, Fraser still thinks about the morning of Nov. 11, 2016. She said there’s no way that noise could have come from Helen falling down from a normal standing position. She must have climbed up a chair or something similar.

Helen told her that she wanted to clean the lights before she fell. Along with lymphoma, Helen also has dementia. She is one of 17,000 Nova Scotians with dementia accoring to the Alzheimer Society of Nova Scotia.

As Nova Scotia’s senior population rises, one in four residents will be 65 or older by 2030, according to Nova Scotia’s 2017 Nova Scotia’s Action Plan for an Aging Population and many are not getting the mental health services they need.

The reasons are complex: Nova Scotia struggles to attract enough doctors, psychiatrists, and other health-care professionals because of low pay and lack of resources. At the same time, Nova Scotia grapples with a shortage of nursing home beds and only has one psychiatric inpatient unit for seniors — and that facility only has 19 beds.

Doctors and seniors advocates are deeply concerned about this state of affairs.

There is also concern from some of the province’s health-care professionals that, because of the delays caused by the amalgamation of the health authorities, the province is not prepared to deal with its aging population.

Wait times

Waiting times for mental health services can be as long as a year for residents living in Cape Breton, and more than three months for those living in Halifax (time it takes to serve 90 per cent of those waiting).

Senior citizens advocate and Atlantic representative for the Canadian Association of Retired Persons, Bill VanGorder, is monitoring the situation closely and said it’s “very concerning.”

“One of the biggest problems is lack of access to immediate services (and) not deal(ing) with a waiting list,” he said.

For health-care professionals such as Dr. Keri-Leigh Cassidy, wait times are on par, despite mounting public pressure to improve them.

“If you’re a person of resource, you may be able to access private psychological services. If you’re relying on public health, then that’s the bane of Canadian health services,” she said. “If it’s access to everyone, then there’s a wait involved.”

Cassidy is the clinical academy leader for the geriatric psychiatry program at Dalhousie University, under the Nova Scotia Health Authority. She said wait times for seniors requiring mental health services at the QEII Health Sciences Centre typically span four to six weeks.

To streamline the wait for mental health services, the Nova Scotia Health Authority introduced the Choice and Partnership Approach in 2013, which aims to fully involve the client in each decision related to their mental health care. Under this framework, a health-care professional will be in touch with someone who is requesting to access care, within three to five months. However, this initial contact is not the same as a medical assessment, which can move a client from primary care to secondary and tertiary care.

“Assessments still take time to happen,” Cassidy said.

Nova Scotia has made improvements to reduce wait times for major procedures, such as hip replacement and cancer radiation, so they meet national benchmarks.

Despite these changes, the, CEO of the Nova Scotia Health Authority, Janet Knox, said there are limitations on what services can be delivered in the middle of the merger of regional health authorities into the Nova Scotia authority.

“While you’re merging, you can’t do everything, so you have to choose that you can’t do everything,” she said.

That said, under the old system, a patient could only receive services in the district where they lived. Now they’re able to receive care all over the province and, ideally, access care where the wait times are shorter.

“When there were nine separate entities, your capacity to do that was limited by the old health districts,” said Nova Scotia Minister of Health Randy Delorey. “Those are the benefits that bring the authorities together; they’re long term, the work that’s ongoing.”

But not everyone, like seniors, can wait.

But this is what’s happening in Cape Breton where geriatric psychiatrist Dr. Jeanne Ferguson lives.

Even though Ferguson is a private psychiatrist, a patient looking for an assessment appointment needs to wait one year. This is because she’s the only geriatric psychiatrist on the island, according to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia website.

Doctor shortages and finding the right care

One essential component to delivering mental health services is having enough health-care professionals and doctors.

Despite Nova Scotia having an academic centre and training hub for the region’s aspiring physicians at Dalhousie University, Statistics Canada says that in 2016, about 10.3 per cent of Nova Scotians 12 years old or older did not have a primary health care provider, defined as “a health professional that a person sees or talks to when they need care or advice about their health.” Statistics Canada says this means more than a family doctor, but also medical specialists and nurse practitioners.

The first step in accessing proper mental health services is having a family doctor who can refer their patient to a psychiatrist. Without enough doctors, people are not getting the care they need.

The doctor shortage continues to stress the already overburdened health-care system, as many physicians prepare to retire. According to Doctors Nova Scotia, 1,300 of the province’s doctors are over the age of 50, while 630 are over 60.

One of the reasons Nova Scotia has struggled recruiting physicians is because it offers lower salaries than other province. The Canadian Institute for Health Information shows that doctors in Nova Scotia can earn anywhere from $10,000 to $100,000 less than doctors in other parts of the country.

cDr. Keri-Leigh Cassidy in her office at QEII in Halifax.When asked about doctor pay being lowest in the country, Knox said there are other factors physicians look at when accepting a new position.

“We talk about pay, but the final analysis is that they really want a good place to be,” she said. “They want to know they’re working with people that’s going to be supportive of them.”

There is one retired and one active physician on the Nova Scotia health authority board, an improvement from last winter when there were none.

Progressive-Conservative leadership candidate and MLA for Cumberland North Elizabeth Smith-McCrossin said a lack of representation of physicians on the executive level for the health authority was symbolic of the fraught relationship between the government and doctors.

“When you’re looking at good decision making, ideally you have people with the knowledge and expertise to make those decisions, so physicians are the most educated health care professionals in the health-care system,” said Smith-McCrossin, who also is the opposition critic for the Department of Health and Wellness.

Shortage of psychiatrists

There are 178 psychiatrists practicing in Nova Scotia, according to the college of physicians site.

As for geriatric psychiatrists, the College website says there are only three in the province, including Ferguson.

Ferguson is the sole geriatric psychiatrist practicing in Cape Breton.

There is also an acute shortage of specialists in geriatric medicine as a whole. Two positions are vacant.

“In the last two years, we’ve fallen off a cliff,” Ferguson said.

Ferguson recently thought the unfilled geriatric specialist positions might get filled by two recent graduates, one from Dalhousie and the other from University of Toronto. But they didn’t like the conditions imposed by the Health Authority and declined the offers.

“We have never been able to get to the bottom of that,” she said. “For me, it was particularly frustrating.”

To alleviate the burden, a geriatric specialist from Halifax travels to Cape Breton and practices there part time.

“We are in bad shape,” she said. “And geriatrics are reflective of that.”

And even where services exist, there are other barriers for seniors.

According to Auditor General Michael Pickup’s report on the province’s health-care system, the province needs to improve its communication strategy on managing health.

“The department and the health authority are doing a poor job of publicly communicating their plans for primary care,” the report said.

VanGorder agreed with the statement and frequently advocates for a streamlined navigation system for accessing care.

“The government does not do a good job of making it known to the public where those services are and how they can be accessed, and people don’t know who to ask or where to look,” he said.

In 2013, the province launched a phone service that can help connect Nova Scotians to health and social programs. The phone service, called 211, is being heavily promoted by government as the first step toward accessing care.

“People do have trouble navigating the complex maze of services,” executive director for the Department of Seniors Faizal Nanji said. “ And what we’ve done is place emphasis on 211 Nova Scotia.”

Having 211 only solves part of the problem.

“The 211 service is a start … but often people need more than that,” VanGorder said. “They need some help getting through the bureaucracy to find out where there are services they can actually use.”

Rachel Boehm, executive director for mental health and addictions for the Halifax region of the Nova Scotia Health Authority, said it’s important for help to be coming from other community networks.

caption

Dr. Rachel Boehm, in her office at the Dartmouth General Hospital.“We just need to make sure that the services do exist and that people are aware of all stakeholders and that we are referring to one another,” she said.

Indeed, awareness is a major concern for seniors in rural areas.

A report done by Atlantic Health Promotion Research Centre and the Nova Scotia Centre for Aging, titled Aging Well in Rural Places, showed that participants in a pilot project about addressing depression among seniors had “a lack of awareness of (mental health) services and how to access them.”

The result is that seniors will leave mental illnesses untreated until it starts affecting them physically, the report said.

Mental health and aging

Physical and neurological health issues can also impact mental health, as seniors may experience a loss of independence and growing isolation.

“Isolation is one of the greatest things that older people have to face as they get older,” VanGorder said.

Both social and geographic isolation are significant barriers to accessing adequate mental health care.

“Seniors experience transportation difficulties and lack family or friends to drive them to places they need to go,” the AHPRC report said

To address this issue, the Department of Seniors is working with other government departments to expand transit in rural Nova Scotia. The 2018 budget tabled by the government has earmarked $2.4 million to expand community transportation under Nova Scotia’s SHIFT action plan on improving the lives of aging citizens.

“Transportation is something we’ve heard when we consulted with seniors in Nova Scotia,” said executive director for the Department of Seniors Faizal Nanji. “I think we can make a big difference when it comes to social isolation by providing solutions for transportation.”

Isolation can also exasperate existing mental health concerns and is typically associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression, and suicide. According to a 2014 report done by the National Seniors Council, “approximately 50 per cent of men over the age of 80 report feeling lonely” and have the highest suicide rate of all age groups.

To combat this problem in the U.K., the government appointed a minister of loneliness to reduce social isolation among the country’s 11.8 million seniors. Both Cassidy and Ferguson agree that something similar should be done in Nova Scotia.

“The number one need for seniors is community,” Ferguson said. “Churches used to be that. Tim Horton’s is the new community centre.”

That is, if you can get there.

caption

Janice Fraser, in her office building in Burnside.In addition, both stigma and ageism impact the ability for an elderly resident to access care they need.

“The barriers of when you have a serious mental illness, (are) it might be more difficult to find a nursing home placement, depending on how the disease affects you,” Boehm said.

Seniors are also inclined to engage in self-stigma where they fail to recognize feelings, patterns and behaviours in themselves as mental illness, due to shaming and ostracization within their community.

In rural areas, this is can be true.

The report done by the Atlantic Health Promotion Research Centre noted that seniors in one community felt nervous about going to the mental health office at their hospital. This is because it was in the basement, at the end of a long hallway, where they would pass many people.

For older men, especially, the idea of seeking help is not just shameful, but unthinkable.

“They’ve always been used of being in control of everything in their life,” said VanGorder. “There’s tremendous pressure put on men when they’re not in control anymore.”

Willow Hall

Seniors with significant mental health challenges may be referred to Willow Hall, the only inpatient mental health unit for seniors in the province.

Opened in 1995, Willow Hall treats dementia and other mental illnesses for seniors that require hospitalization. Sometimes, Willow Hall admits seniors who were placed in nursing homes, but their behaviour becoming unmanageable at the nursing home level.

There are 19 beds for the unit’s 19 patients who each follow their own unique routine based on the type of care they need.

caption

A panorama shot of Willow Hall.Ultimately, the goal of Willow Hall is to get patients back to where they lived before they arrived, whether that’s a nursing home or their own residence. But since nursing home beds are scarce and the wait-list long, sometimes a patient can’t go back right away or at all.

“You can’t leave a nursing home bed vacant waiting for someone to get back,” Boehm said.

The team at Willow Hall works closely with the Department of Continuing Care, which oversees nursing homes, to make sure each patient’s needs are aligned with the services of the home. If they can’t find a match, the patient has to wait at Willow Hall.

Boehm said around 40 per cent of hospital patients are waiting for long-term care, not just nursing homes.

Since Willow Hall serves the entire province, there will often be admittance requests from seniors living in Cape Breton. The only problem is that Willow Hall is almost always full of seniors who could go to a nursing home bed, if only beds with appropriate care were available.

“So new patients can’t get in,” Ferguson said. “That goes on months after months after months; there’s no exit strategy for those patients, and they could get into nursing homes.”

According to the Mental Health Commission of Canada, there should be one to 1.5 full-time equivalent staff and four other health-care professionals for every 10,000 seniors.

Willow Hall is nowhere close to that standard.

“If you have take 10,000 seniors, the number of those who would might need mental health, who might need inpatient care, we would need to have a 40 bed unit in order to serve the province,” Cassidy said.

Willow Hall has about eight staff members overseeing the 19 patients. Since opening, the unit has had the same number of beds and Boehm said there are no plans to increase the number.

When asked why the province has not followed the staff recommendation of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, Health Minister Randy Delorey said the government receives many recommendations from different organizations, some of which don’t always line up with the province’s priorities.

“We continue to make significant investments as well as continuing the work to learn from the clinicians and the clinical advice,” he said. “Where we’re at as a province doesn’t always line up with other external organizations would suggest.”

Nursing homes

As mentioned, Helen Fraser ended up finding a home at Northwood, a place she’s called home for over a year.

Since arriving she’s been able to not only interact and chat with other clients, but receives daily visits from her children. During one visit, she was sitting in a corner of her room, chatting with her daughter while watching the History Channel and stroking her robotic cat, Gigi.

The cat, which Helen believes is real, was a gift from her daughter. Gigi turns her head drastically at times and lets out a soft purr whenever Helen starts to talk to her.

“We wouldn’t let anything bad happen to you,” Helen tells Gigi.

caption

Helen Fraser, with her robotic cat Gigi, at Northwood.For seniors like Helen with significant health challenges, they may need to be placed in a nursing home for a longer period of time. Social workers and nurses offer around-the-clock care. as well as occupational and recreation therapy.

But, like health care, there is a long wait and a personnel shortage.

Overall, it takes 176 days to place half the people waiting for a nursing home space in Halifax. In Cape Breton Regional Municipality, it takes about a year. Some homes have longer waits than these.

There were 1,021 people waiting for a long-term placement in Nova Scotia as of spring 2018.

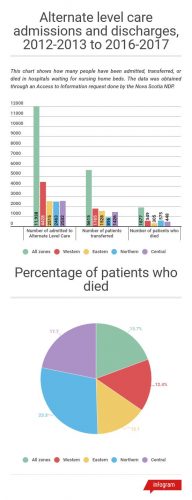

According to documents obtained through access to information, 1,877 people died while still waiting for beds at nursing homes in Nova Scotia from April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2017. In addition, 2,281 people were waiting in hospitals for nursing home beds, further stressing the bed shortage in hospitals. Around 123 of those people were waiting for more than a year.

“This government has not opened one long term care bed,” said health critic for the NDP Tammy Martin.

“There’s not one dollar increase this session. And if we don’t invest in long term care bed, we’re not going to see a resolve of the bed shortage, ER backlogs, and residents dying before they get into long term care.”

Geriatric psychiatrist Dr. Jeanne Ferguson said when seniors stay in hospitals for months, waiting for a nursing home bed, they receive no exercise or mental stimulation.

To relieve pressure on the nursing home bed wait-lists, the government invested in home care with a $400 supplement given to caretakers of an elderly loved one. the program was recently expanded to allow 600 more people to receive the supplement.

“We know that Nova Scotians want to stay in their home as long as they can and that reduces the pressure on the long term care system,” Health Minister Randy Delorey said. “Do we still see some pressure? Yes.”

A 2017 report done by Auditor General Michael Pickup showed the province had failed to fulfill eight out of 12 recommendations made nine years ago to address home care weaknesses. Those weaknesses include quality assurance of delivery in care, accuracy in reported hours by service providers, and not knowing whether the province is ready for future demand.

This spring’s budget included a $5.5 million additional investment in home care.

Due to the demand, seniors need to take the first bed available to them and would, possibly, need to move away from their loved ones.

“I can’t tell you the guilt associated with that,” Ferguson said. “I’ve had people come into my office and sit there and sob because they feel so guilty of putting their loved ones in a home.”

caption

Francella FiallosSometimes, couples who have been married for 30, 40, or even 50 years may have to be separated, if one or both individuals need long-term care.

This was the situation for Tammy Crossland’s grandparents.

Edwin and Marjorie Crossland are in their 90s and have been together for 70 years. When Marjorie’s health declined as her dementia got worse, she needed to be put in long-term care at Orchard Court in Kentville. Crossland’s grandfather, who was in a hospital at the time, was assessed by continuing care providers and deemed too healthy to join her.

Crossland was dumbfounded.

“He’s diabetic, he has agina, poor circulation due to cardiac issues, he uses a walker to walk, but he’s unstable but he can’t stand without assistance,” she said, holding back tears. “He can’t walk without that walker and he is on an antidepressant because he can’t talk about that situation or my grandmother without crying.”

Knox said travelling to receive care is just the reality.

“We can’t say that no one has to travel at all; we just don’t have a money tree,” she said.

But that wasn’t good enough for Crossland, so she found and appealed her grandfather’s assessment.

After dozens of phone calls, letters, emails and meetings, Crossland’s grandparents were reunited. This came about after the Health Authority said on March 23 her grandfather did meet the requirements for long-term care. He’s now down the hall from his wife at Orchard Court.

“They’re happy to be together,” Crossland said over an online messenger.

Crossland’s grandparents’ reunion is a rare case. Long-term facilities haven’t increased the number of staff in 14 years as they have experienced two years of one per cent budget cuts under the Liberal government.

Oakwood Terrace in Dartmouth had to cut $86,000 from their budget last year, while Northwood had to trim $600,000. Nursing homes consider saving money by using over-the-counter prescriptions and cutting back on energy, for example.

Since there’s not enough staff to monitor clients, for those who require more attention, nursing homes resort to other means. Many nursing homes will use restraints on clients, or belting, to keep them from harm’s way. However, it is only used when all other options have failed, according to the least-restraint policy the government mandated in 2007.

Kim Smith knows all about the different restraints used in nursing homes. She was a continuing care assistant hired in 1985 and witnessed a decline in care for patients.

Fed up with what she calls the “politics” of nursing homes where keeping up appearances was more important than serving the patients, she left in November 2016 after 31 years.

“It just seemed like management over the last, our management anyways, over the past several years, it was all for show. Let’s paint inside, let’s re-decorate, everything looks good in here,” she said.

“In reality, behind the scenes, we were rushed, rushed, rushed.”

As part of Smith’s terms of employment, she couldn’t publicly name the home she worked at.

Ferguson said she has to deal with the repercussions of nursing home “politics” every day in her practice.

“We know that you’re more prone to delirium when you’re belted to a chair,” she said. “I’ve asked to have a patient not be belted, and was told that that will not happen.”

While Smith-McCrossin would like to propose many changes to nursing homes in the province, if selected as leader of the PC Party. She said she would make sure the least-restraint policy is respected.

She saw first-hand how staff shortages can impact nursing home clients when her grandfather, who had dementia, was one in 2010.

Smith-McCrossin’s grandfather stayed at Highcrest Nursing Home in New Glasgow. Staff would set up alarm system before bedtime to alert personnel if a wandering dementia patient tried to leave the home.

But one evening, during a snowstorm, they didn’t.

Smith-McCrossin’s grandfather left the home and walked into the storm. He was quickly found by nurses, but died the next day, partly from the cold.

The Nova Scotia Health Authority

The doctor shortages, the wait-lists, bed shortages and overall gaps in care existed well before the amalgamation of the Nova Scotia Health Authority, but health-care professionals and seniors advocates believe the merger was a step backward, not forward.

Nova Scotia used to be comprised of nine district health authorities, but they amalgamated in 2015 to streamline services and cut back on administrative costs. The decision to merge has been met with heavy criticism from some of the province’s physicians and health-care professionals, who in 2017, wrote an open letter decrying the decision.

“The NSHA expects patients to fit its distribution of services, policies, and procedures, without explaining the rationale, or adequately involving patients and providers in the planning, implementation, and review,” the letter said. “How is this patient-centred?”

With regards to the aging population, the letter specifically points that it’s “extraordinary” the province is “so under prepared.”

One of the authors of the letter is Dr. Ajantha Jayabarathan, a family doctor in Halifax who has expressed frustration with the Department of Health and Wellness through media appearances and a column in The Chronicle Herald.

caption

Dr. Ajantha Jayabarathan.At first, she was excited about the amalgamation because it was going to bring primary care in hospitals to the forefront.

But her excitement was quickly extinguished. She claimed that in 2015 Dr. Rick Gibson, Senior Medical Director for the Nova Scotia Health Authority, informed her and her colleagues doctors would need re-apply to the new health authority. She said doctors would need to show the department their medical credentials, even though some doctors had been practicing for decades.

“I thought, okay, maybe this was their way of figuring out who was out there,” she said, even though the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia already had this information.

Jayabarathan believed this was the government’s way of keeping track of who was qualified to do what, which tests they could run and, ultimately, how much cost they would incur.

More changes were made, such as imposing quotas on where doctors could practice at a time where hundreds of physicians were expected to retire. The quotas are part of the province’s Physician Resource Plan which uses a variety of metrics, such as population needs, equitable distribution and affordability to place physicians in regions across Nova Scotia.

“If they wanted to shut down the number of doctors, they could have waited for the attrition to happen and use that time to build the partnerships they did, and built up nurses, new doctors,” said Jayabarathan. “They could have still looked after the people we serve.”

Instead, Jayabarathan and other doctors believe the one centralized health authority is doing the opposite.

“You could talk about pulling the rug out from the entire system, they pulled the rug right out,’ she said.

According to freedom-of-information request made by the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union, the merger cost taxpayers more than $9 million.

Jayabarathan said if improvements aren’t made the province will not be able to handle the influx of baby boomers requiring health care.

“It’s going to be catastrophic,” she said. “We all see it. We get it and we get it in our guts.”

Dr. Jeanne Ferguson agreed with Jaybarathan’s viewpoint. From her perspective, if changes to the health authority aren’t made, the rest of the province could begin to look like Cape Breton.

“The bureaucracy has been unresponsive and about as easy to turn around as the Titanic,” she said.

The Health Authority has said they face many challenges and has asked everyone to have patience, as the NSHA is still trying to develop its organizational culture.

“The culture of an organization probably takes a decade (to form),” Knox said.

In Knox’s office in Bayers Lake, she has a list of values from the Health Authority pinned next to her computer screen so that she is always reminded of what’s important.

“We are asking people to be accountable. We come to do good work on behalf of people of this province and to have integrity of that. When we don’t do good work, and when people tell us that, we have to be open to that.”

But Smith-McCrossin said they’re not doing enough.

“The last year they have been like Band-Aiding, putting Band-Aids on all the bleeding parts of all the province,” she said.

SHIFT action plan

In 2015, the provincial government announced a three-year strategy to address dementia. VanGorder said out of the 11 deadlines imposed by the province for implementing the strategy, only two have been accomplished so far.

“It’s ridiculous,” he said.

Still, VanGorder feels a bit more optimistic about a 50-point government action plan devoted to improving the lives of senior citizens.

The action plan, called SHIFT, was announced last March, a year after the Liberal government proposed changes to the province’s pharmacare plan which angered many seniors. Eight government departments, including the Department of Health and Wellness, the Nova Scotia Health Authority and the Department of Seniors will be responsible for implementing the $13.5 million dollar plan.

“We need to change the way we think about the older population,” Nanji said. “We need to see the older population as an asset.”

Examples of items include improving access to healthy and affordable food, investing in affordable housing and promoting an inclusive job market.

Most provinces and territories have their own strategy for senior health care. For example, New Brunswick’s strategy is squarely focused on providing high quality long-term care while Newfoundland and Labrador has promoted healthy aging, according to the Canadian Medical Association in a 2016 report on seniors’ health care. The World Health Organization defines healthy aging “as the process of developing and maintaining functional ability that enables well being in older age.”

The CMA report found that, while most provinces emphasize the importance of seniors’ mental health, Quebec stands out for recognizing mental illness and cognitive problems as “a fundamental health issue.”

Nova Scotia’s SHIFT plan stressed the need for the government to take on a more “comprehensive approach to improve the mental health of seniors.”

In last fall’s budget, the Liberals boosted health-care spending by $6.2 million. As part of this year’s budget, the Liberals have tabled a $19.6 million multiyear plan to recruit and train doctors, as well as a $2.9 million increase to mental health care.

VanGorder, who was consulted during the creation of the SHIFT plan, said it’s a step in the right direction.

“We always hesitate to be too excited when we’re talking about plans and strategies and we’ll be happy when we see results,” he said.

Additional spending to support Nova Scotia’s aging population was presented in the spring budget, most notably through the $2.4 million expansion of community transportation, but nothing specifically to address seniors’ mental health.

Cassidy, who was also consulted on the creation of the SHIFT action plan, said it was never intended to have specific health recommendations.

“The leadership of health as it relates to seniors is not addressed in the SHIFT strategy,” she said. “It may have indirect positive results, but not enough to solve the issues of health care.”

Still, VanGorder was especially impressed by Premier Steven McNeil’s mandate letter after last spring’s election, in which the Liberals won their second majority government. In it, McNeil mentioned the SHIFT action plan by name saying that it’s an “excellent example of collaboration across government and with many other individuals, groups and institutions to support older adults.”

Others have said the plan is not enough.

For Smith-McCrossin, this is another example of the government neglecting to consult with people who are directly impacted by its decisions.

“They’re not focused on people that they’re trying to serve. A lot of these plans, they’re a lot of theory. There’s a lot of philosophy’ we need to change our focus in health care to how can we make it better for the patient,” she said.

When the plan was announced last spring, chair of the Seniors Advisory Council of Nova Scotia Bill Berryman felt tnot enough money was earmarked to accomplish all 50 recommendations. Thanks to the boost mental health services in last fall’s budget, Berryman now feels more optimistic the plan can succeed and has touted its efforts to other senior groups he works with.

“I presented it to at least four areas of the province,” he said. “I did a presentation a couple weeks ago to the federation of seniors. I fully support it. I wouldn’t present it if I didn’t support it.”

caption

Family photos on the wall of Helen Fraser’s room in Northwood.Fraser said she and her brothers visit with their mother daily, even though they don’t live in Halifax. Otherwise Helen will fall through the cracks.

Or, with Helen’s dementia, she will forget who they are.

Many of the clients at Northwood don’t have many or any visitors. Some of them have even begun to view Fraser as one of the staff, someone who can help them when they need it, talk to them and keep them company.

While Helen is social with the other clients, she knows that she would be lost without her children taking care of her. Only her children know she shouldn’t be lifted out of bed with her neck. Only her children know that Gigi likes to be pet in a certain way. Only her children know her.

“She looked right at me on Friday night and she looked at me dead serious, and said, ‘I wouldn’t be able to stay here if you guys weren’t coming to see me all the time,’” Fraser told her sister-in-law Pam.

“I said, ‘mum you know all kinds of people here.’ And she said, ‘you know what I mean.’

And I said, ‘I know what you mean.’”

Editor's Note

This story was completed in fulfillment of requirements in the King's MJ program. The reporting was completed between January and April 2018 and updates have been made to reflect current information.

About the author

Francella Fiallos

Francella Fiallos is completing her master's in journalism at the University of King's College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She is the programming...