Actions speak louder than words

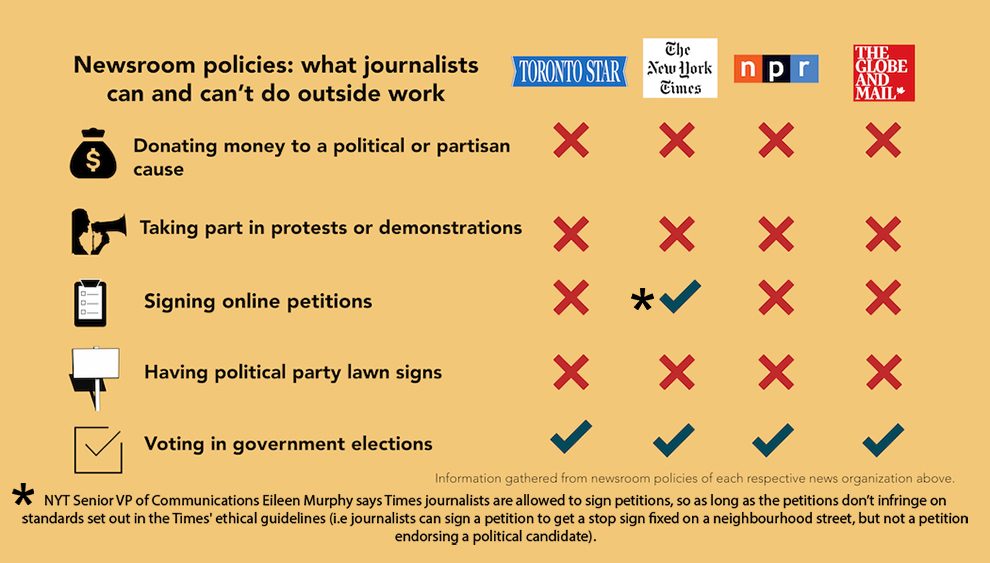

caption

Journalists’ attitudes towards activism are shifting. Are newsroom policies keeping up?

John Miller sat in front of a clunky, grey Underwood typewriter. The click-clacking of teletypes and rotary phones and the occasional slurp of coffee could be heard in the newsroom. It was the winter of 1984, and Miller had been working at the Toronto Star for 15 years. That year, his newsroom faced reader backlash for inconsistent reporting. Miller’s managing editor was fed up, and told him to do something – anything.

At the time, Miller was the Star’s deputy managing editor. When he began to write the Star’s first comprehensive newsroom conduct policy, his workload doubled. So he assembled a committee to help him put together a manual. It was going to look like the one at the New York Times.

Filed away in the newsdesk drawer were several memos. Most of them were quick tips for good practices in the workplace, written by former Star newsroom chiefs. Miller sent the memos back and forth to about eight reporters. For three months, the committee brainstormed to create what is now known as the Toronto Star Newsroom Policy and Journalistic Standards Guide.

“I was a little apprehensive with publishing it, because I didn’t want to overly restrict our reporting,” Miller says. “And I didn’t want it to be something that people would regard with derision.”

Thirty years later, there’s one guideline that Miller regrets not adding to that first edition: columnists can be activists.

Irony, 30 years in the making

On May 4, 2017, Desmond Cole quit his Toronto Star bi-weekly column. Two weeks earlier, at a Toronto Police Services Board meeting, Cole stood with his fist in the air, refusing to leave until the board made a commitment to restrict police access to information gathered from carding. The board didn’t. Twenty minutes later the meeting adjourned.

Carding is the police practice of collecting personal information of people not suspected of any crime. It is an issue that Cole has written on in columns and features.

After his protest Cole was called into the Star’s editorial page editor’s office. Andrew Phillips handed Cole a document that said journalists must refrain from “any open display of political or partisan views on public issues.” Cole left the editor’s office, fuming. The next evening, he wrote his resignation letter.

Cole’s departure has journalists questioning whether newsroom policies are keeping up with journalists’ shifting attitudes about activism. And whether activist-journalists, like Cole, should have the freedom to pursue activism without fear of reprisal.

“People in John’s position have a choice,” Cole, who is black, says. “Especially as white people who have established positions in the media. They have a choice to be silent or to speak out. And he spoke out.”

John Miller might be Cole’s biggest champion. He was quick to defend Cole’s resignation in an article he wrote for Rabble.ca. Cole was wronged, Miller says, because of a policy written more than 30 years ago.

Miller’s problem with the 1984 policy he helped create is that it makes no distinction between reporters and columnists. Reporters and columnists, he says, are not one and the same.

Paul Adams, an associate professor of journalism at Carleton University, agrees. Writing in iPolitics in May 2017, he followed Miller’s lead in criticizing the Star’s treatment of Desmond Cole.

Adams believes it’s “perfectly reasonable” for newsrooms to govern what staff reporters can and can’t do outside work. But that power shouldn’t stifle the voices of columnists, who – unlike reporters – may have been hired because of their activism.

Factors that editors should consider when assessing this ethical dilemma, Adams says, include: whether the writer is a freelancer, columnist or reporter; what they stand for; how they act; and what they write about. Adams says staff or freelance reporters shouldn’t cover issues in which they are invested. Columnists, though, are “a different kettle of fish.” They should be allowed to cover and pursue activism, Adams says, so long as they’re honest about it with their editors and readers.

Miller and Adams both agree that news organizations would benefit from inviting more activists to write opinion columns more regularly.

“We shouldn’t treat partisans and activists as if they are pariahs in public debate,” Adams says. “They are people we want to hear from. A lively news organization should have those voices.”

Both ends of the spectrum

“The notion of objectivity,” Cole says, “is one of the biggest, central lies of how people practice journalism in this country. It’s not possible to be objective.”

It’s more important, Cole thinks, for columnists to be honest about their vested interests than to waste efforts in being objective.

Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel expressed a similar thought in 1997, when they wrote the seminal book The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. They wrote that objectivity, even then, had lost its essence. Rather than aim for objectivity, Kovach and Rosenstiel called for journalists to use transparent methods in their reporting,. Meaning: journalists and news organizations should disclose the ways in which they gather information, and any apparent conflicts of interests.

“News organizations have struggled,” Ivor Shapiro says, “for a century or more, to define the limits of their employees’ human responses to unjust situations.”

Shapiro, a professor of journalism at Ryerson University, says that there is a long history of journalists rejecting the notion of objectivity. At the same time, the great majority of news organizations still expect writers to be objective. Even after leaving the office for the day.

caption

Graphic by Fadila ChaterThe New York Times, Guardian and Globe and Mail rules of conduct demand all staff members be balanced, fair and impartial. The Times’ Ethical Journalism handbook directs “all members of the news and editorial departments” to not “march or rally in support of public causes.”

Shapiro points out that news organizations didn’t always strive for objectivity.

Joseph Howe threw a few rotten tomatoes when he was owner and editor of the Novascotian. In 1835, one particularly rotten tomato landed him in court for seditious libel. His call for press freedom won the case, and inspired generations of Canadian journalists to hold the government accountable.

From 1899 to 1948 Joseph E. Atkinson was publisher of the Toronto Star. The Atkinson Principles – principles that promote social justice – are what the Star says it follows still today.

The activism-journalism relationship exists on a spectrum, Shapiro says.

Imagine a line. At one end is the term “activism” and at the other end the term “objectivism.” Organizations like Vice, Rebel Media and Breitbart News lie near the “activism” end, while the New York Times, Canadian Press and Associated Press sit closer to the “objectivism” end. The line isn’t fixed. Organizations move along the spectrum as they change principles or ownership over time. Newsroom policies, Shapiro says, will reflect these changes to ensure the organization’s reputation is intact.

But there are more journalists today, like Desmond Cole and Catherine Porter, who aren’t ashamed to protest, picket or speak at rallies, despite what the rulebook says.

Like Cole, Catherine Porter was a Star columnist. Today she’s a foreign correspondent for the New York Times. At the Star she championed women’s rights and community activism. In July 2015 she wrote a column about her nine-year-old daughter’s first protest, and run-in with Ezra Levant, a well-known conservative. Porter’s activism was a focal point of her writing at the Star. She says her editors encouraged it.

For this reason, Cole says, the Star’s “policy is selectively enforced.”

Ivor Shapiro agrees. News organizations like the Star, he says, aren’t always “consistent or logical” when enforcing policy. “There’s reason and then there’s policy,” Shapiro says. “Sometimes it’s just gut.”

Kathy English begs to differ. On May 4, 2017, the Star’s public editor wrote in a column that her colleagues had every right to be concerned with Cole’s protest. English cited the Star policy that tells journalists to “avoid active participation in community organizations […] that take positions on public issues.” Cole’s actions, she said, unlike Porter’s, “go beyond advocacy.”

At the time English said she saw “merit” in a conversation about revising current policies, particularly when it concerns columnists. Six months later, she still holds that opinion.

Journalists have the “latitude to express their opinions in a column,” English said in an interview. But certain kinds of activism are out of line with one’s position as a columnist at the Star. “I don’t know what the line is,” she says. “I’m really not there yet. I haven’t reached a conclusion.”

English revealed that the Star’s newsroom conduct policy will be undergoing an “overhaul.” As part of this, she says, the Star will reconsider the guidelines outlining “policies of columnists’ participation.”

John Miller, who led the writing of the first policy, in 1984, hopes newsrooms loosen rigid policies so columnists can pick up megaphones and march with the masses. Newsrooms, Miller says “should encourage their columnists to be activists.”

“The world has moved on,” Carleton’s Paul Adams says. “The world that John was addressing, when he wrote those ethics guidelines, has moved on.”