Advocates continue to push for reparations for African Nova Scotians

Activist says every African Nova Scotian community has been disadvantaged by history of racism

caption

Lynn Jones has been advocating for reparations for years.Members of the African Nova Scotian community continue to make a case for reparations, but say a lack of political representation means their voices often go unheard.

Reparations cover a broad scope, but all forms of reparation are meant to redress disadvantages African Nova Scotians continue to face today as a result the province’s history of slavery and institutional racism.

Lynn Jones, a community activist in Halifax, has been advocating for reparations for years. In an interview, Jones pointed to well-known instances of institutional racism in Nova Scotia as some of the more obvious examples of why reparations are needed.

The treatment of Africville residents, who were marginalized and then forced to relocate when the city destroyed the community, is one example. Another is the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children, where an inquiry found a history of abuse against black children spanning decades.

“It doesn’t mean that they’re the only ones, or even that they’re the ones that have the most claim,” said Jones. “But they are the most blatant.”

But ultimately, Jones said, any African Nova Scotian community could make a claim for reparations. This is because they continue to experience a ripple effect of socio-economic disadvantage as a result of a legacy of systemic racism.

Legacy of socio-economic disadvantage

Black Nova Scotians have difficulty accessing wealth and the effects of inadequate schooling and subpar housing are still felt, said Jones.

The 2016 Canadian census showed the unemployment rate of African Nova Scotians to be 1.5 times higher than white Nova Scotians, while twice as many African Nova Scotians live in low-income households.

“One would think everybody’s starting at the same place whether you’re white or black,” Jones said. “But if your family has had wealth, or even education over a long period of time, that’s passed on one from one generation to the next.”

Monetary compensation could help African Nova Scotians overcome economic disadvantages, but Jones said compensation does not equal reparation.

Reparations: no one size fits all

Jones believes Canada’s history with slavery has had lasting, wide-ranging impacts on African Canadian individuals and communities. Slavery was made illegal in all British colonies in 1833, but Jones said it laid a foundation for systemic, institutional racism in this country, from which black communities are still recovering.

The negative impact has been broad, said Jones, making it difficult to create a template for what reparations should look like in Nova Scotia.

“Discrimination, anti-black racism, health issues, healing issues, economic issues. It covers every spectrum you could possibly imagine,” she said. “So it depends on what your experience is, how reparations unfolds.”

Some work done, but much more needed

In November, Halifax Regional Police apologized to the African Nova Scotian community for racial profiling in the practice of street checks. In the past, Halifax has apologized for its mistreatment of the residents of Africville, and Nova Scotia has apologized for the abuse that occurred in the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children.

Additionally, the provincial and federal governments have recognized the United Nations Decade for People of African Descent. A UN report recommended Canada “consider providing reparations to African Canadians for enslavement and historical injustices.”

In response, Canada committed money toward community and employment programs for African Canadians. Nova Scotia created the Count Us In action plan to answer some of the recommendations from the UN report, but Jones was disappointed to see no explicit mention of reparations within the plan.

She said money and apologies are only steps toward reparations.

Jones would like to see the provincial and federal governments put resources toward researching the most appropriate form of reparations for each black community, based on the specific disadvantages they have faced.

“You can never pay for what happened during slavery. It can’t be done,” she said.

Because the impact of racism in Canada has been so broad, Jones believes there is no template for reparations.

“You can’t do one thing and claim you’ve got reparations,” she said. “It’s got to be going on for generations and generations and generations.”

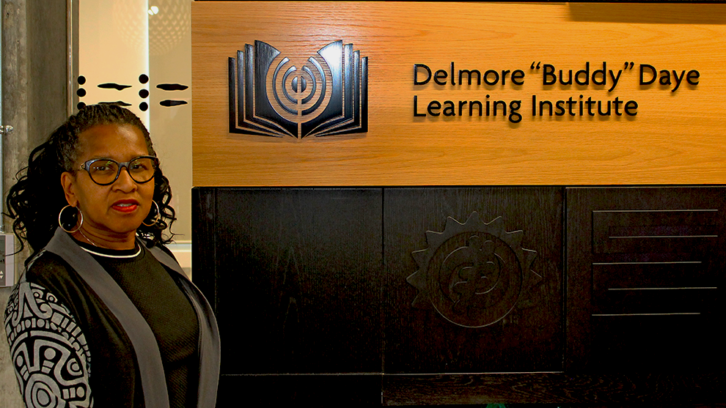

caption

Sylvia Parris-Drummond is CEO of the Delmore Buddy Daye Learning Institute.Sylvia Parris-Drummond agrees. She’s CEO of Halifax’s Delmore Buddy Daye Learning Institute, an educational organization that provides resources and services for African Nova Scotians.

“We’re talking about things that are embedded in structures,” she said in an interview. “That leaves all of us trying to pull at it from different aspects to unravel it and shape a fabric that works for all of us.”

Problems persist across generations

Marcus Marsman, a second-year law student at Dalhousie University, recently spoke on a panel about reparations with Jones as part of African Heritage Month.

He said the Black Loyalist settlement communities of Nova Scotia are a good example of why a blanket solution for reparations doesn’t work.

In the 19th century, the British gave land to Black Loyalists without title of ownership. That meant people who lived on that land couldn’t sell, mortgage or lease it. And since the settlers didn’t technically own property, they couldn’t vote.

Two hundred years later, many African Nova Scotians in these communities still don’t have clear titles of ownership for their land. Without clear title to land, residents could have legal troubles selling their property, or building on it.

For the 13 Black Loyalist settler communities in the province, Marsman said clearing up land titles could be one appropriate form of reparation.

In 2017, the Nova Scotia government announced it would implement the Land Titles Initiative to help residents clear up the ownership of their land. The province has committed $2.7 million to help cover the fees of gaining clear land title, or ownership.

Need for political action

Marsman said a lack of African Nova Scotian representation in government makes it difficult to make progress on reparations in the province. He noted the first black MLA in Nova Scotia wasn’t elected until after he was born in 1993. Since then, only a handful of African Nova Scotians have served in the legislature. Right now, Tony Ince is the only black MLA in the province.

caption

Marcus Marsman wants more political representation for African Nova Scotians.“This is significant, because primarily any sort of progressive action is going to happen through the legislative assembly,” said Marsman.

“In order to effect change, you need seats in the house and people who are sympathetic to the cause.”

Under the current government, Jones said, the issue of reparations is “a political hot potato that nobody wants to touch.”

Because of a lack of political representation, she said an unfair burden is placed on communities to advocate for redress.

“Not only [do] we have to educate our own community on what is happening, but then we are also supposed to be expected to educate government,” she said.

“I think the key is that everyone should have reparations on their agenda.”

Jones will be involved in a forum discussion on reparations on Feb. 29 at Halifax North Memorial Library.

About the author

Ethan Lycan-Lang

Ethan Lang is a student journalist at the University of King’s College. Originally from the Annapolis Valley, he spent a few years on the Rock...