An inconvenient quagmire

caption

Graphic by Heather Norman.Reporting on climate change is complicated. It is also vital.

Andy Revkin is fascinated by the way journalists report on climate change. Revkin, the senior reporter for climate and related issues at ProPublica in New York, used to work as a professor and environmental communications researcher at Pace University in Lower Manhattan.

He would start his course Blogging a Better Planet by having students take 30 seconds and write down what they thought climate change was. “Invariably,” says Revkin, “they’re all over the map.”

That’s because climate change means something different to different people. Without providing the proper context to his students – for example by referring to it as “human-caused climate change” – it was impossible for them to know exactly what he was talking about.

The same thing applies to journalists, says Revkin. Without providing a clear definition of the issue, throwing the words “climate change” into a story does little to inform the reader.

Even when journalists provide the necessary context, there simply isn’t enough coverage of the issue, says Lucy McAllister, a visiting professor at Boston College and a researcher for the Media and Climate Change Observatory based in the University of Colorado-Boulder. And McAllister has also found that the coverage that does exist is often inaccurate or sensationalized.

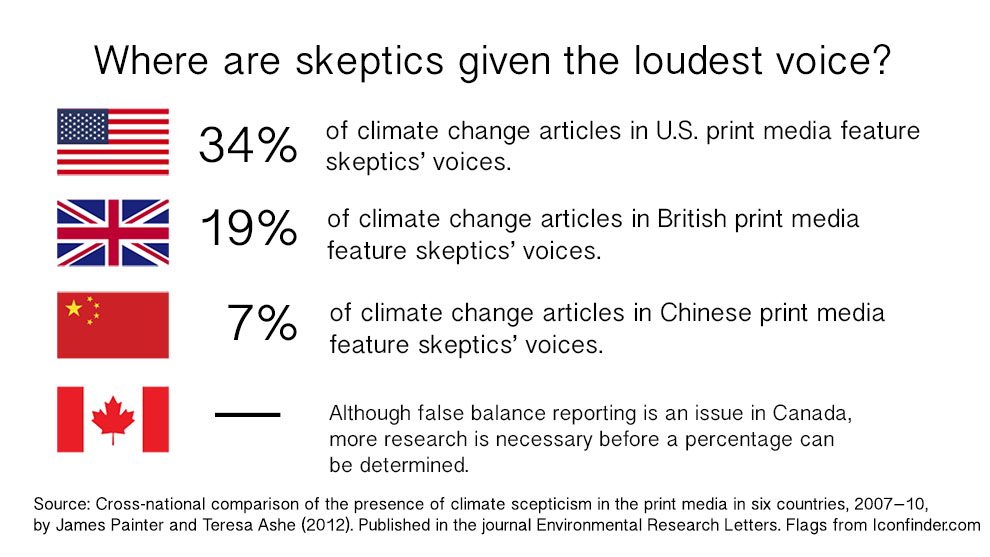

Ninety-seven per cent of climate scientists agree that humans are the leading cause of climate change. Yet, according to The Consensus Project, an online resource started by John Cooke, a leading climate communication researcher at the University of Queensland in Australia, 34 per cent of all climate change articles in the U.S. treat the consensus as if it’s a 50/50 split.

This is what researchers call false balance reporting. When media outlets give the same consideration to an uninformed climate skeptic as they do to a scientist who has spent years studying climate change, says McAllister, “balance becomes bias.”

The Observatory, which monitors 52 media outlets across 28 countries, uses archived stories from online databases to monitor how often these outlets consider climate change and global warming. The findings are updated monthly. The data started in January 2000, and focuses on large newspapers around the world.

Coverage of climate change increased globally from January 2006 to an all-time high in December 2009, coinciding with the release of Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth, the fourth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment report, and various international conferences on climate change.

Following the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference in December 2009, media coverage of climate change experienced a dramatic decline. The three Canadian newspapers studied by the Observatory, the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, and the National Post, dropped from a total of 585 articles on climate change in December 2009 to just 225 a month later.

In Canada now, the Globe reports on climate change most often, while the Post reports on it the least. Although Canadian coverage has largely stagnated over the last year, the coverage of other news organizations, including the New York Times and the Guardian, has been steadily rising.

caption

Graphic created by Heather NormanQualitative studies

Mark Stoddart, a professor and researcher at Memorial University in Newfoundland, has conducted two studies on the coverage of climate change in the Globe and the Post. In a 2015 study in the journal Environmental Politics, Stoddart and his co-author, David Tindall, examined the media coverage of climate change from 1999-2010.

The study found that while the Globe’s reporting was focused on the government’s response to climate change, and the role of climate change in extreme weather, the Post focused on the unreliability of climate science and the economic impacts of climate change.

Stoddart says that while the Post reports on climate change more like American papers, most Canadian media tends to differ from the U.S. style of reporting. “Unlike the American media landscape, where you’re bombarded by the believer vs. denier binary, in Canada I think we’ve got a system where you can just plug in to the newspaper that reinforces your view.”

In a study published in 2015 in the journal Public Understanding of Science, Lauren Feldman, a journalism professor at Rutgers University, examined the coverage of four newspapers in the U.S., including the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, from 2006-2011. She found that the Journal was the least likely to discuss the threat of climate change, and the most likely to frame actions addressing climate change as an economic burden.

“The most important thing with an issue like climate change,” says Feldman, “is trying to honour and respect what we know from the science.” That becomes more difficult, Feldman suggests, as newsrooms shrink and need to redistribute resources from science reporting to other areas. When this happens, typically a journalist unfamiliar with the science is forced to cover climate change issues.

Newsroom cuts aren’t entirely to blame: the problem is exacerbated by scientists who don’t know how to speak to journalists. McAllister, at Boston College, says this means journalists are often left to interpret scientific jargon on their own. “Scientists aren’t trained to talk to people without a PhD.”

More than a political issue

Climate change is widely considered a significant global security threat, according to the results of a survey by the Pew Research Center released in August 2017. The survey had 41,953 respondents from 38 different countries rank eight different security threats, including “Islamic militant group known as ISIS”, “cyberattacks from other countries”, and “the condition of the global economy”.

“Global climate change” was ranked the number one global threat in Canada and much of Latin America, while it came third in the U.S.

Although climate change is one of the most—if not the most—significant global threats currently facing the world, says McAllister, it lacks the immediacy of terror attacks, the refugee crisis, or even the Trump presidency.

This is one of the biggest challenges the media faces reporting on climate change: it’s a long-term problem. And, McAllister says, it’s one many people are tired of hearing about. Climate change has been in the news for a long time. It’s difficult to report on an issue where the newest developments are often, though not always, political. That’s why conferences and agreements, like the Copenhagen Conference in 2009 or the Paris Agreement in 2016, drive climate change news.

While political coverage is certainly an important aspect of climate change reporting, McAllister says, it shouldn’t be treated as the only one. Climate change is also a social issue. This means highlighting the impact it can have, and has had, on marginalized groups. “Those least responsible for creating the problem—less developed countries with vulnerable populations—are now facing the worst impacts of our changing climate,” says McAllister. As the developing world navigates a hotter climate, issues of social inequality are magnified. Yet, these stories rarely make it into the news.

Robert Hackett, a professor of communications at Simon Fraser University, says that media outlets need to give a voice to those marginalized by the issue. In his book Journalism and the Climate Crisis (2017), Hackett defines the “hope gap” in climate change reporting.

“It’s important to offer solutions and celebrate successes,” says Hackett. People-centric stories that examine what individuals are doing to combat climate change are an important way to diversify climate reporting.

Making climate change matter

Over the course of his tenure at Pace University, Andy Revkin wrote 2,810 posts for the Times blog Dot Earth, which he started in 2010 as a way to explore the relationship between the Earth and its booming human population. Returning to journalism at ProPublica in 2016, Revkin says, felt like an opportunity to revisit the themes and issues he’d spent six years blogging about.

Revkin has written extensively about why he originally left journalism. He didn’t want to spend the rest of his career in a vacuum, writing more award-winning articles on climate change without ever being able to make the issue matter to his readers.

Now, Revkin says he knows that reporting on climate change needs to be about more than just the political or sensational. “People who would be utterly divergent, who would fight forever about global warming, can be totally in sync on clean energy,” he says. Regardless of political views, people want to learn more about things like renewable energy, regulating carbon dioxide and even improved battery technology.

Journalists need to make sure that they aren’t missing the big picture. Although political stories are an important part of climate change journalism, they don’t tell the whole story. More articles about clean energy and solutions, and more stories about the everyday people impacted by climate change are necessary to humanize the issue and have readers accept its complexity.