International Politics

As turmoil in Venezuela escalates, Halifax student fears for family members

Venezuelans face high crime, hyperinflation, hunger, medicine shortages

caption

Silvia Daboin, 22, is an engineering student at Dalhousie.Silvia Daboin still remembers seeing her father in tears, declaring that Venezuela is no longer safe for them to live in. He had just been kidnapped and robbed while at a gas station.

“He somehow managed to get home. I just remember him sitting on the edge of my bed with my mom crying and he said, ‘I can’t live here anymore, I’m getting my children out of here, I’m not raising them in this country,’” Daboin said.

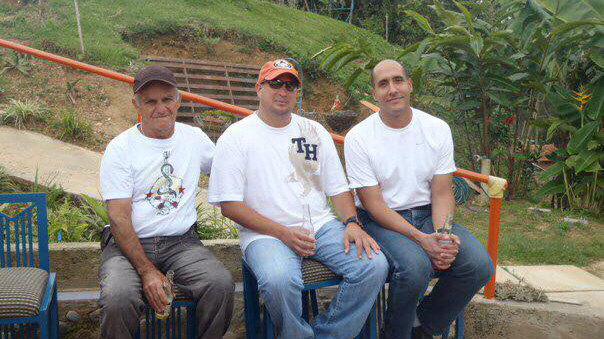

caption

The family fled Venezuela after her father (right) was kidnapped and robbed while at a gas station.Daboin, 22, is safe in Halifax, while her parents live in Calgary. She is studying engineering at Dalhousie University, but she consistently checks on family members who are still in Venezuela.

“There’s close to nothing available for them and it’s just so dangerous. My mom has to give my grandma money every month for her to be able to live comfortably. They live in constant fear,” Daboin said.

“There’s no medicine there; there’s no food. My grandma, every time she comes to visit us, she takes medicine from Canada to there.”

Venezuela ranks among the world’s most dangerous countries. In a 2017 survey, 42 per cent of respondents said they had money or property stolen and around 25 per cent had been assaulted. Only 17 per cent felt safe walking home at night.

Food scarcity is one the country’s major issues. A survey, conducted by the country’s National Assembly in 2017, estimated that Venezuelans on average lost about 24 pounds of body weight that year.

The Canadian government urges travellers to avoid Venezuela unless it’s essential. A travel advisory cites “the significant level of violent crime, the unstable political and economic situations and the decline in basic living conditions, including shortages of medication, food staples and water,” as reasons why.

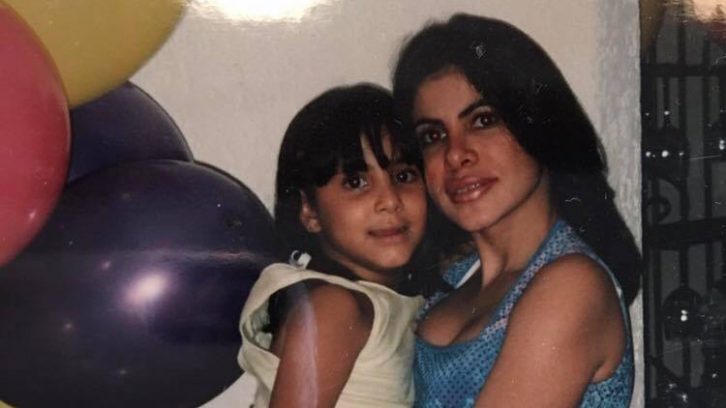

caption

Daboin and her aunt. Her aunt fled to Colombia and they have not seen each other in six years.Daboin was born in Maracaibo, a northwestern city in Venezuela. Her parents worked for the state-owned oil company, PDVSA, until 2002. They took part in the 2002 oil strike in protest of former president Hugo Chavez’s policies and, along with 18,000 PDVSA employees, were fired as a result.

The final straw for the family came the following year, when Daboin’s father was kidnapped.

Daboin and her family fled Venezuela in 2003, and eventually ended up in Calgary, due to the city’s oil industry. She now considers Canada her home, and has not been to Venezuela in eight years, but she stays connected to her relatives through phone calls and social media.

“I feel like I’ve completely lost my culture, like I have no connection to Venezuela anymore, socially, and it’s not because I wanted to. It’s because of how things have ended up,” said Daboin.

“It’s just very hard to keep a connection with a place you can not only visit, but you can’t even get into contact with usually.”

caption

Daboin has not been to Venezuela in over eight years.Daboin voted for the first time as a Venezuelan in a referendum in 2017. The referendum was called after President Nicolás Maduro’s attempt to change the constitution. The pro-Maduro Supreme Tribunal of Justice, Venezuela’s highest court, attempted to dissolve the opposition-led National Assembly, leading to a constitutional crisis. Due to international pressure, the tribunal reversed the decision and the National Assembly called for a referendum.

Daboin went with her mother to a shopping mall in Calgary to cast her ballot.

“It was completely packed; there was lines of Venezuelans outside the mall doors and into the parking lot,” she said. “It was really nice to see that there’s so many people supporting, even if you’re so far away and living in a completely different country. We all still care so much about our country and want to see it prosper in the end.”

The result of the referendum was a 99 per cent vote against Maduro’s agenda, which led to a presidential election in 2018. Maduro was re-elected for six years.

Daboin has been in Halifax for four years, where there are around 100 Venezuelans compared to Calgary where there is over 3,000. She graduates next year and is unsure about working in Venezuela, but wants to help the country.

“It’s more that I just don’t know with the information I have, or what I am able to do without putting myself in danger,” she said. “If there was opportunity for me to help, I 100 per cent would, and I definitely want to in the future.”

C

Carolyn

C

Charles Clarke

J

Joseph McCoy

S

Shannon