Blurred Lines

caption

Caption here.Does the lucrative relationship between ESPN and the NFL threaten the credibility of ESPN’s journalism?

The National Football League’s biggest fan is not who you’d expect. He doesn’t participate in fantasy football, isn’t a slave to Sunday games, and doesn’t enjoy hot wings and beer. He never played football in high school, has never purchased a ticket to the Super Bowl, and doesn’t wear the jersey of his favourite team.

The NFL’s biggest fan is rich – think theme parks rich – and has a vested financial interest in the sport’s future. He’s from Hollywood, the star of more than 130 feature films, and famous for wearing red shorts, oversized yellow shoes, and sparkling white gloves. Two large and funny-looking ears protrude from the top of his head.

Mickey Mouse loves football.

An unlikely hero

Mickey Mouse is, of course, the official mascot of the Walt Disney Company. Recently listed by Forbes as the world’s eleventh most powerful brand, Disney’s market value was estimated at more than $178 billion as of March 2015. Surprisingly, their major revenue source doesn’t derive from theme parks and resorts, or from the release of blockbuster films such as The Avengers or Star Wars.

Instead, the unlikely hero in Disney’s quest for profit is ESPN, the Entertainment & Sports Programming Network. “ESPN is the driving factor of Disney’s media networks division. There’s nothing close,” says Forbes senior editor Kurt Badenhausen.

The business operations of Disney are divided into five major segments: media networks, parks and resorts, Walt Disney Studios, Disney consumer products, and Disney Interactive. According to Disney’s third-quarter earnings report for fiscal year 2015, the media networks segment (comprised of ESPN, the Disney Channel, and ABC) accounted for just over 44 per cent of $38.9 billion in revenues, and almost 53 per cent of $11.1 billion in operating income.

“ESPN is the most important individual division at Disney in terms of value and the profit that it generates for the parent company,” says Badenhausen.

As a contributor to Forbes’ annual list of the world’s most valuable brands, Badenhausen has charted ESPN’s brand value for several years. He says ESPN is worth more than $60 billion today, making it the most valuable media company in the world – and more valuable than companies such as Home Depot, Gucci, Starbucks and J.P. Morgan.

According to Badenhausen, ESPN’s immunity to viewer time-shifting allows it to generate significant advertising revenue and sky-high affiliate fees. As other television programming has suffered at the hands of illegal streaming, enhanced recording technology, and shifting viewer patterns, live sports continue to offer broadcasters significant reach and live-audience delivery. A 2012 analysis by Discovery Communications, using Nielsen ratings data from 2011, concluded 94 per cent of sports programming is viewed live.

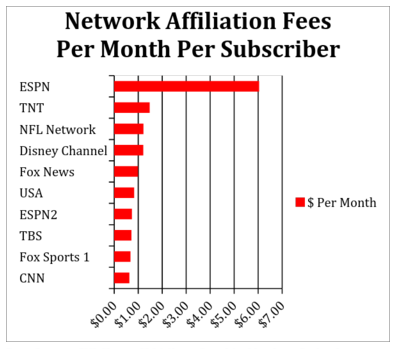

caption

Data Source: SNL Kagan (2014).This has helped ESPN become the most expensive cable network on television, costing cable providers an average affiliate fee (the price paid by cable providers to broadcast ESPN per month, per subscriber) of $6.55 according to 2015 estimates by leading media research firm SNL Kagan, of Charlottesville, Va. ESPN’s average affiliate fee is more than four times the fee to broadcast the next most expensive network, TNT.

ESPN has built its empire by acquiring these valuable rights to programming across almost all major sports. Still, ESPN owes much of its value to its crown jewel: football. ESPN’s financial partnership with the NFL is worth almost twice as much as the NFL’s contracts with Fox, CBS, and NBC. And with ESPN having secured – for $15.2 billion – broadcast rights to the NFL through the 2021 season, Badenhausen says its dominance is unlikely to end any time soon.

“People are obviously cutting back, but football seems to be the one thing that people will never cut back from.”

Football puts money in Mickey’s pocket.

The Magic Kingdom

At the same time the mutually beneficial relationship between the NFL and its largest broadcasting partner presents a natural conflict. As former ESPN ombudsman Robert Lipsyte says, “ESPN and the NFL are business partners, which makes ESPN’s coverage of pro football a conflict of interest.”

caption

Toiling in the trenches: A 2014 study by Harvard University and Boston University found that offensive linemen suffered roughly six times more suspected concussions than players at other positions.Richard Deitsch is a writer and editor for Sports Illustrated, and an adjunct professor of sports journalism at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. The veteran scribe has covered six Olympic Games, several Super Bowls, and worked for nearly every division of Sports Illustrated (including SI For Women and SI For Kids). Though he doesn’t believe that ESPN is telling its reporters to favour the league on an individual reporter level, he says ESPN’s corporate thinking is influenced by its relationship with the NFL.

“The enabling that happens by its on-air people at times is absurd and too many ESPN on-air people have tentacles in the league. They are not journalists, but (are) often in journalistic roles.

In August 26, 2003, the first episode of a new television show called Playmakers aired on ESPN. It was the network’s first original drama series, and focused on the players and staff of a fictional American football team. The show’s first scene focused on the psychological impact of football’s violence, and subsequent episodes highlighted rampant drug use, sexual promiscuity, and racial prejudice within the professional football community.

Though the words “National Football League” were never uttered, the NFL was not impressed by the show’s content. In a 2003 interview with Bob Costas on HBO, Commissioner Paul Tagliabue accused the show of “trading in racial stereotypes.” Philadelphia Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie went one step further in an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer. “How would they like it if Minnie Mouse was portrayed as (drug kingpin) Pablo Escobar and the Magic Kingdom as a drug cartel?”

Despite the show’s strong ratings, Playmakers was cancelled by ESPN in early February 2004. According to the New York Times, the cancellation came after Tagliabue complained about the show to Michael D. Eisner, the CEO of Walt Disney – ESPN’s parent company.

“It’s our opinion that we’re not in the business of antagonizing our partner, even though we’ve done it, and continued to carry it over the NFL’s objections,” then-ESPN executive vice-president Mark Shapiro told the Times. ”To bring it back would be rubbing it in our partner’s face.”

ESPN would face more questions in July 2009. Only months after quarterbacking the Pittsburgh Steelers to a Super Bowl victory, Ben Roethlisberger was accused of sexual assault in a civil lawsuit filed in Nevada. The story was first reported by NBC’s Pro Football Talk website on July 20, and soon picked up by most other major sports websites. The exception was ESPN, and by the following afternoon, ESPN had become a part of the story. “Is Big Ben a no-fly zone for ESPN” wondered the Wall Street Journal. Sports blog Deadspin accused ESPN of “ignoring [the] biggest stories of the day.” An anonymous source told NBC that ESPN had distributed a “do not report” memo about the story to its employees without explaining why.

“There has been no criminal complaint against Ben Roethlisberger and he has no track record of the behavior,” ESPN director of news Vince Doria told the New York Times, in defending ESPN’s decision to not report the story.

In March 2010 Roethlisberger was investigated again, for a sexual assault that allegedly took place in the bathroom of a Georgia nightclub. Charges were not filed, but Roethlisberger was suspended for six games by Commissioner Roger Goodell for violating the NFL’s personal conduct policy.

caption

Head Bangers: A 2011 study published in The Annals of Biomedical Engineering determined that the average collegiate football player sustains 1,000 sub-concussive impacts to the head over the course of a season. Sub-concussive impacts can cumulatively damage brain tissue, but are mild enough not to cause immediate symptoms.For its part, ESPN has consistently denied the NFL has any influence over its editorial decisions. ESPN’s senior director of communications, Bill Hofheimer, declined an interview request, but said in an email that the network’s partnership with the NFL has never affected its relationship with the audience.

“ESPN serves fans by covering all on-the-field and off-the-field aspects of the league aggressively on a daily basis. The NFL and its teams recognize we are a news organization and expect fair coverage.”

Hofheimer pointed to the network’s coverage of concussions, domestic violence issues, and the “Deflategate” scandal as illustrative of ESPN on a variety of NFL issues. “While ESPN does have a business relationship with the league, we maintain a church-versus-state approach in terms of our editorial coverage.”

Misinformation

The issue of domestic violence would rear its ugly head toward the NFL on Valentine’s Day 2014. At the Reveal Casino Hotel in Atlantic City, Baltimore Raven Ray Rice celebrated the occasion with his fiance (now wife) Janay Palmer. After dinner, the couple was seen arguing as they headed into a hotel elevator. Four days later, TMZ released video of Rice dragging an unconscious Palmer out of the elevator. After several months of investigation, the NFL suspended Rice for two games.

On September 8, 2014 – the morning after the first Sunday of the NFL season – TMZ released a second video. Like Mike Tyson putting down Michael Spinks in Atlantic City in 1985, the video showed Rice knocking Palmer out with a vicious left hook. The clip was replayed endlessly, and shared widely on social media. The Ravens terminated Rice’s contract later than afternoon; the NFL levied an indefinite suspension.

ESPN, Hofheimer pointed out, led the coverage of the Ray Rice scandal. Much of the information detailed above comes from an ESPN “Outside The Lines” investigation led by Don Van Natta Jr. that “found a pattern of misinformation and misdirection employed by the Ravens and the NFL.” One of the central questions of the story was why – or whether – the NFL failed to obtain the inside-elevator surveillance tape between February 15 and September 8.

ESPN personality Bill Simmons weighed in on his weekly podcast, the B.S. Report. In a profane rant, Simmons questioned Goodell’s authority and accused him of lying about the second videotape.

“Goodell, if he didn’t know what was on that tape, he’s a liar. I’m just saying it. He’s lying,” said Simmons. “For all these people to pretend they didn’t know it is such fu—-g b——t… I was so insulted.”

Simmons also dared ESPN to punish him for his comments on Goodell. “The commissioner’s a liar and I get to talk about that on my podcast… Please. Call me and say I’m in trouble. I dare you.”

Simmons’ comments were not backed up by any of his own reporting, and immediately drew the ire of ESPN. He was suspended for three weeks, with ESPN issuing a statement saying that he “had failed to meet (the) obligations” of ESPN’s journalistic standards. The length of his suspension drew criticism on Twitter – both for being one week longer than the initial suspension handed to Rice, and two weeks longer than the suspension given only months prior to fellow ESPN analyst Stephen A. Smith for insinuating that women sometimes provoke domestic violence. Many, including Washington Post reporter Wesley Lowery, also questioned the reasoning behind the suspension: “What exact ‘journalistic standard’ did Bill Simmons – a personally branded columnist and analyst – violate? Speaking ill of the NFL?”

Sports Illustrated’s Deitsch believes that Simmons angered management, including Disney management, with his threats. And though he thinks that ESPN judged Simmons “under the prism of a reporter who should not be making statements without reporting,” he says the lack of consistency with ESPN discipline ultimately hurts the brand. “Most viewers will look at the punishment for Simmons versus the non-punishment for Smith and ask about the NFL’s influence.”

‘Clumsy shuffling’

The relationship between ESPN and the NFL faced its most bruising public scrutiny in the wake of ESPN’s 2013 withdrawal from the co-production of a documentary with PBS Frontline. League of Denial was the culmination of a 15-month investigation by PBS and ESPN into “the hidden story of the NFL and brain injuries”.

The New York Times drew a parallel between ESPN’s withdrawal from the documentary and its 2004 cancellation of Playmakers. The Times reported the withdrawal stemmed from a “combative” meeting where NFL representatives voiced their displeasure with the documentary’s tone. Robert Lipsyte, ESPN’s then-ombudsman, reviewed the decision and concluded “at best we’ve seen some clumsy shuffling to cover a lack of due diligence. At worst, a promising relationship between two journalism powerhouses that could have done more good together has been sacrificed to mollify a league under siege.”

The Poynter Institute’s Kelly McBride, one of the foremost voices in media ethics, was the lead writer for the Poynter Review Project. The project – a panel of Poynter faculty – served as ESPN’s ombudsman before Lipsyte. She echoed Lipsyte’s sentiments in a 2013 column: “It’s one thing for journalists to ask tough questions. It’s completely different for journalists to provide the answers to those tough questions. And that’s where ESPN couldn’t seem to go with the NFL.”

Deitsch says that sports permeate every part of our society, from race to gender to economics. As such, sports journalists owe it to their audience to maintain the standards of journalism. While journalists should “seek truth, minimize harm, and act independently,” he said, this “was an example of business interests outruling journalism issues at ESPN.”

Players were also miffed at ESPN’s decision to withdraw from the documentary. NFL Players Association senior manager of communications Mike Donnelly declined an interview request, but referred to a statement NFLPA spokesman George Atallah gave to the Huffington Post in August 2013. Atallah told the Post: “I think any time that business interests get in the way of telling an important story like the one Frontline was working on, I think that that’s a sad day, regardless of why or who or what the circumstances were.”

Faced with mostly negative feedback, ESPN changed course. It would eventually promote the documentary – and an accompanying book written by ESPN reporters and brothers Mark Fainaru Wada and Steve Fainaru – on the network. Van Natta Jr. recapped the book’s findings in a column for ESPN.com. These actions earned begrudging respect from Lipsyte, who praised ESPN journalism for “winning ugly.”

Lipsyte wrapped up his tenure as ESPN ombudsman in November 2014. Now retired – but still writing – he says “winning ugly” is an apt description of the battle between ESPN’s business model and editorial process.

“ESPN’s heavy hitters – like the Fainaru brothers – did well on the concussion story despite the network’s wimping out by removing its logo from the show. And ESPN did allow them to follow the story. But by removing its logo, ESPN diminished the story’s impact among hardcore sports fans, an important audience that should know the price its heroes are paying to entertain them, a price that ESPN’s business partner, the NFL, went to great lengths to obscure.”

The NFL, through Vice President of Football Communications Michael Signora, declined to comment.