Brand new venture

caption

Is the line between journalists and content creators clear?How influencer culture and social platforms are affecting newsrooms

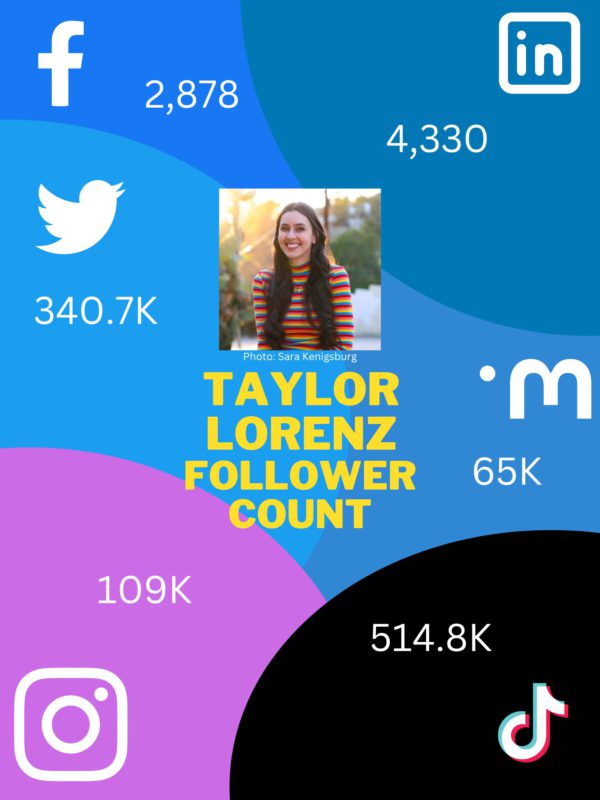

Taylor Lorenz predicted influencer culture would permeate newsrooms. She made the forecast in a 2018 NiemanLab post, then revisited it two years later.

It’s her job to spot trends. Lorenz writes a column for The Washington Post, covering Internet culture and technology.

Before that, she was a technology reporter for The New York Times. She was poached from The Atlantic in 2019. Lorenz owns the tech culture beat. The Times’ Styles desk got tired of her pulverizing them on all things digital. It happened thrice in one month, sending counterpart Kevin Roose into a self-described ‘shame spiral’ for days.

She’s a millennial — unless you ask the far right.

Lorenz’s forecast: Journalists would prioritize personal brands, grow their followings and leverage social platforms — building a large, loyal following to shield themselves from volatility.

She knows what she’s writing about. Lorenz’s career began as a content creator on Tumblr in 2009. Blogging allowed her to develop a voice and audience on her own terms. “That was very powerful,” she says. It led to work in digital media, then legacy newsrooms.

She noticed high-profile journalists and writers leaving major publications in 2020 and 2021 to create digital newsletters with Substack, where audience reach and posts could be monetized.

“I can totally see why commentators would do that. Their jobs are very unstable. Media companies are constantly laying people off,” says Lorenz. “Digital media has cratered. There’s not really places to work.”

More than 360 newspapers in the U.S. have shuttered since late 2019 — most are weeklies — according to The State of Local News 2022 survey from Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. The report was updated last June, tallying 6,380 papers: 1,230 dailies and 5,150 weeklies.

Since 2005, “when newspaper revenues topped $50 billion, overall newspaper employment” has dropped 70 per cent “as revenues declined to $20 billion,” the report, by professor Penny Abernathy, reads. Newsroom employment is down nearly 60 per cent.

Founded in 2017, San Francisco-based Substack provides writers with infrastructure to house newsletters that go directly to subscribers. If writers want to bill readers, it takes a 10 per cent cut, plus credit card transaction fees. The platform is a space for podcasting, too.

Lorenz has a newsletter. She uses it sparingly to create posts similar to a Twitter thread. “I always need to write more but I get busy and you know, Substack doesn’t pay me,” she says. “I don’t make any money from it.”

caption

Photo: Sara Pearl Kenigsberg; Illustration: Jake WebbSolo superstars

Several big names are all in with Substack. Others are dabbling. Writer and cultural critic Roxane Gay, Vox’s Matthew Yglesias, and tech scribe Casey Newton have launched newsletters.

The minimum amount writers charge readers is $5 per month. Rates are tiered. An April 2021 Times headline sums it up: Why We’re Freaking Out About Substack.

University of Iowa journalism professor David O. Dowling knows the digital sphere. “I think self-branding and self-promotion is definitely in journalism right now, and you see it with the move to Substack and Instagram,” says Dowling.

He has deep respect for social media. It offers the ability to connect, yet creates a yearning for independence. “The notion of authorship gets collectivized and becomes horizontal because we have more technology,” says Dowling. “What happens is people will push back against that and try to individualize.”

In 2012, Times reporter John Branch wrote Snow Fall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Peak. He accepted a 2013 Pulitzer Prize and Peabody Award. Dowling cites the story as an example of the strive for independence. A team created the iconic multimedia feature — making ‘snow fall’ an industry verb — yet only Branch received public praise.

Upon accepting the Peabody, Branch immediately acknowledged being the “frontman” and credited four female colleagues standing with him.

Offense and defense

Layoffs at large U.S. newspapers and digital news sites subsided in 2021 after increasing a year prior, Pew Research Center finds. It’s possibly linked to the economy adding 6.4 million jobs, and less journalists overall to eliminate from newsrooms, researchers say.

Times CEO Meredith Kopit Levien was asked about Substack in November 2021, according to Axios, telling investors anything that helps “make the market for paid digital journalism” is good.

Email newsletters aren’t exactly innovative. Compared to the onslaught of information in browsers, aggregated content is evergreen.

How did Substack soar? By wooing writers with six figures via its contentious Substack Pro program. It was offering a yearly stipend upfront, in some cases, to mitigate risk. This was during the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

“That’s when a lot of popular commentators began leaving and doing Substack full-time,” Lorenz says, adding it’s not ideal for hard news reporters. Opinion and/or commentary writers are finding the most success “because ultimately, reporting generally takes a team and you need pretty robust legal protection,” says Lorenz. Pilot program Substack Defender was launched in July 2020, offering legal support to U.S. users.

The platform is a solid business option for writers “that didn’t make it in traditional media,” Lorenz says, or failed — like controversial journalists Bari Weiss and Glenn Greenwald. They’ve built “very successful businesses.” Weiss makes more than $800,000 per year. Her platform has a careers section with postings for editorial, marketing and podcasting jobs.

Where does that leave journalists who want out of newsrooms — or seek maximum exposure — but don’t have hot takes?

For the ages

Emma Bentley, 23, left the BBC last summer for a startup. The News Movement primarily uses short-form video app TikTok. Bentley wants to create content she actually cares about. At the BBC, “I was filming things that I wouldn’t watch myself. It was catering to a demographic that was very far from my own,” she says. Bentley is in London, creating videos on pop culture and news. She has more than 54,000 followers.

TikTok’s algorithm rewards quantity over quality. Similar to working in newsrooms, the digital economy comes with tremendous challenges: unrelenting burden to create; financial pressure; blurred professional-personal boundaries; fear of getting cancelled; overall precariousness. There’s also the unforgiving hours, navigating customer relations, and demanding audiences — essentially, a shortcut to burnout.

Age can factor into the willingness to ‘bet on yourself’ with a social media-driven enterprise like YouTube. “I think slightly older journalists struggle because they’re a bit fearful of new things,” says Bentley. They’re typically in a better position, financially, to take a risk.

Lorenz believes the hesitation stems from resentment. “People that came up in the traditional legacy media world, many of them have a deep hostility toward people who came up through the Internet,” says Lorenz. Those tensions are playing out, she adds, and traditional newsrooms are struggling “to retain digitally native talent.”

What about Gen X? Anthony Quintano, 44, is a former NBC photojournalist. He’s based in New Jersey and has 32,000 followers. Quintano has a corporate day job. “I’ve embraced TikTok because of growth,” he says.

It’s the perfect platform for broadcasters to flex their personal branding muscles. FOX5 DC’s morning anchor Jeannette Reyes is known for using her ‘anchor voice’ outside of the studio, often with husband Robert Burton, in funny, engaging videos. He’s a morning anchor at competitor ABC7. Reyes has 1.3 million followers.

@msnewslady How people think anchors talk at home #tvcouple#6abc#abc7#foryoupage#fyp

Lorenz believes more newsroom leaders should be embracing digitalization. “If you have a condescending attitude towards young people or consuming new information, that’s only going to hurt you,” she says. Her WaPo and Times editors are “amazing.” But CNN is “becoming totally irrelevant because it’s led by these people that don’t understand the internet.”

Options are oxygen

Charlie Warzel left the Times in April 2021 — he didn’t accept the shiny Substack deal — creating his newsletter, Galaxy Brain. Working solo, he attracted 16,000 subscribers, with 1,400 paying for his content. It lasted seven months.

He announced he was heading to The Atlantic, Galaxy Brain included, offering readers a free 12-month Atlantic subscription.

In Warzel’s final Substack post, he wrote “I’m worth more to a publication as part of a package of writers/reporters/thinkers than I am on my own.”

Nicci Kadilak has hundreds of subscribers. She writes about local politics in Burlington, Mass. It’s a town of roughly 26,000 people. Kadilak, a former teacher, is a mother of three and likes having a flexible schedule.

She started a hyperlocal newsletter, Burlington Buzz, last February. It took seven months to acquire 800 readers and The Buzz is in a period of “strong growth.” Her current goals? Surpass 1,000 readers by the end of this year and acquire 1,600 by 2024.

Kadilak may accept commissions for other publications. She also writes books, “but Substack is my news publication,” she says. “I don’t work full-time for any one entity. I work for myself.”

Why did she choose Substack? Support and professional development opportunities, like virtual conferences. Kadilak attended over the summer to learn. “It’s all about building brands and that takes time,” she says, “and the more time you have to devote to actually interfacing with your audience, the faster your growth will be.”

Brian Morrissey, the former president and editor-in-chief of Digiday, told Vox newsletters are “a great minimally viable product.”

But it’s competitive.

“Certainly, very smart people with very meaningful messages get passed by all the time in favour of the ones who are the loudest and flashiest,” says Kadilak.

About the author

Jake Webb

Jake Webb is a fourth-year student in the Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) program at the University of King's College.