Breaking from the news

caption

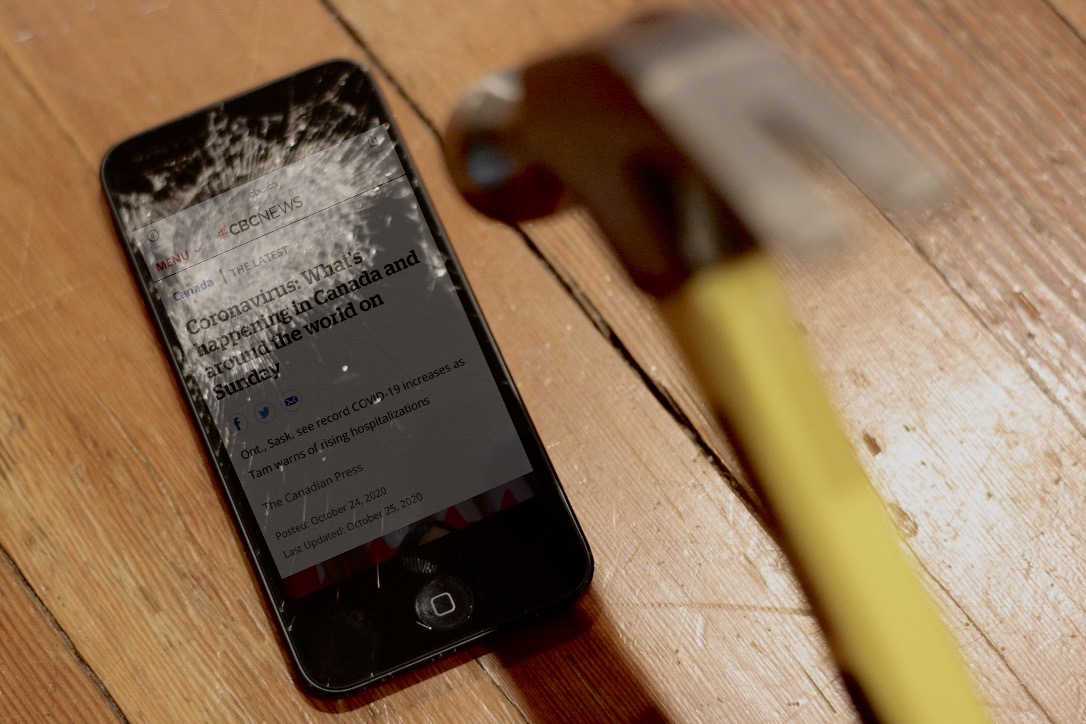

A cellphone gets smashed in this photo illustration.Journalists need to take breaks from the news – to preserve their mental health

Sitting at her desk at the Globe and Mail, Ann Rauhala stares at a large, economy-sized bottle of Tylenol. It sticks out from the controlled chaos of her small office. The room has no outside windows, just a phone and computer. The pills are starting to feel as though they have become a necessary snack for her brain.

Being the foreign editor and a weekly columnist used to be fun. Not anymore. She just finished her third news meeting of the day. Her daily routine has become a constant fight against time. Between writing, editing and phone calls, she never has time for a break. It wasn’t until she started to calculate bathroom breaks that she realized her job was a burden.

The 24-hour news cycle became overwhelming.

“If you are devoting all of your energy [to] everything that is going on in the news,” says Rauhala, “you can quickly lose control of your own emotions and become disproportionately affected by what you are seeing.”

Her stress kept getting worse when Rauhala went on to work for another news outlet. Raising a toddler and the expectations of a journalism career were not a good match anymore.

She decided to look for other work. Today, she is a journalism professor at the Ryerson University in Toronto. And has been for the last 20 years.

Rauhala’s case is not rare. Journalists are at high risk of burnout and are predisposed to trauma. They often report on car accidents, fires and murders. River Smith, a postdoctoral fellow in clinical psychology at the University of Tulsa, directed a 2017 Dart Center study which found that more than 86 per cent of journalists are exposed to traumatic work-related events at some point in their careers. These events have consequences.

An Australian study conducted in 2016 by Jasmine B. MacDonald, a professor at the School of Psychology in New South Wales, and published in the journal Substance Abuse, found that journalists are more susceptible to substance abuse due to the nature of their work.

To avoid being attracted to unhealthy ways of dealing with their trauma, journalists have to take regular breaks from the news.

Since Rauhala started teaching, she has implemented more healthy routines into her life. The most effective are daily meditations. Rauhala tries to meditate at least twice a day, for 5-20 minutes each time, and says “the effects are just so immediate.” Along with meditation, Rauhala has found that turning off screens after 8 p.m. has improved her sleep. These steps help her to manage the constant flow of information that is an integral part of her job.

caption

Our phones are handy, compelling and give us so much – sometimes too much.

Reality of the job

Elana Newman, head researcher for the DART Center for Journalists & Trauma at Columbia University in New York, says post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in journalists is more common than many people realize. Many reporters witness fires, are exposed to court testimony and videos, or cover gang violence, wars and executions.

Newman wants to help minimize the trauma that journalists are exposed to, so that they can continue to do their important work. For her, getting journalists to work collectively on self-care practices will not only help them, but the profession. In July 2020, Newman participated in a Zoom panel hosted by the (U.S.) National Association of Hispanic Journalists on how reporters are handling the pandemic’s impact on the Latino community. Some of the journalists on the panel shared that when working from home they find it harder to power down.

Breaking point

When a traumatic event takes place, reporters aren’t far behind paramedics or police officers. Jesús Ayala, a former ABC reporter based in Orange County, CA, spent 16 years collecting accounts of trauma. In one year, he covered Hurricane Katrina and an earthquake in Haiti. “I didn’t have one traumatic event that contributed to my PTSD,” said Ayala. “It’s an accumulation.” In his experience the journalists who put their lives at risks are rewarded, some with better stories, others with Pulitzer Prizes.

“Journalists are first responders,” says Ayala. But unlike other first responders, journalists are not there to help people who are suffering, but are spectators at the scene.

One day, he decided it needed to stop. He is now a journalism professor at the University of California, Fullerton. “Sometimes it’s not really about one event,” said Ayala, “it’s almost like a file cabinet. You just kind of file it, file it, file it and eventually there is no filing room and your body wants to take care of it.” This is when most reporters break down, feeling obligated to push through it.

Higher up

When a journalist reaches their breaking point, they should be able to talk with their editors or producers. Over time, the industry has been changing, and allowing for more conversations centered around mental health.

Peter Lozinski, editor of the Daily Herald in Prince Albert, Sask., is trying to make sure his team knows they can talk to him if needed. Since the beginning of the pandemic the coverage of the virus has been divided between all of the reporters. He says that COVID-19 has added some stress because everyone has to “make sure that everything you do is right and that you don’t contribute to wrong information.” To cut down his own stress, he has recently decided to take nightly breaks from social media. He still makes himself available to his team, but tries to stay away from any new information until the morning. Doing this, he finds he can better handle whatever news breaks the following day.

Lozinski isn’t the only editor doing more to support his reporters. In light of the pandemic, the Montreal Gazette is providing its writers with mental health resources and will help them track down a therapist. But is it enough? Allison Hanes, a reporter for the Gazette, is glad these are available but feels like conversations about extra support are hard to have.

Hanes is sure the door would be open if she wanted to talk about feeling overwhelmed. She considers the editors and journalists at the Gazette as a family. She struggles more with taking the personal step to talk.

“There are days where I certainly felt like it was a real struggle,” says Hanes, “but I didn’t say that. I assume I am not the only person in this situation. To some degree we are all feeling it and maybe not saying it to each other.”

She is wondering how her feelings could be more valuable than those of her colleagues, “why do I get to say I am not doing this today?” Speaking up about feelings is how current and future journalists will become more comfortable with their own way of dealing with their own trauma.

Jesus Ayala talks about the pressure that comes with being a journalist.

New generation

To help new journalists be better equipped for the career ahead of them, Rauhala hosted some mindfulness sessions at Ryerson in 2016. It was only a pilot made possible through a grant, but the goal was to encourage healthier habits for students in order to help them have a better relationship with their work.

More than a dozen students signed up for four weekly one-hour Mindfulness Meditation classes. Before the first one they took a Mind Over Mood anxiety inventory test. After the four sessions, students reported a nearly 40 per cent reduction in anxiety.

Even though the sessions are no longer offered, Rauhala says professors throughout the university have introduced mindfulness and stress reduction components to their syllabi. For example, all first-year Ryerson students were encouraged to practice mindfulness.

RUMindful: Integrating Mindfulness Practice into Teaching and Learning was created two years ago. Rauhala is a founding member, and is joined by other professors who are practitioners of mindfulness and want to raise the awareness of its benefits. They first met informally, but as time went on decided they could do more with what was available to them.

This year, they have launched an online lecture series to spread their knowledge with the rest of the university, and hopefully the rest of the world.

About the author

Kheira Morellon

Kheira is a french immigrant currently living in Halifax. She is passionate about languages and is looking to bring more coverage to the Franco-Canadian...