Brunswick Street development faces appeal from Heritage Trust

Heritage group fighting community council decision

caption

The approved building is to be constructed behind the old rectory (left), adjacent to St. Patrick’s Church (right).The Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia is appealing Halifax West community council’s decision to approve a development on Brunswick Street, over concern for the street’s heritage buildings.

The council approved an eight-storey residential development at 2267 Brunswick St. on July 9. The development is set to be constructed behind the old rectory of St. Patrick’s Church, which is currently a private parking lot and empty lawn.

The Heritage Trust is concerned many buildings will be dwarfed by the new development, while, at the same time, threatening the street’s heritage value.

“In fact, when we looked at it, there was not another street like it in Canada with that much history on it in such a concentration,” said Andrew Murphy, president of Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia.

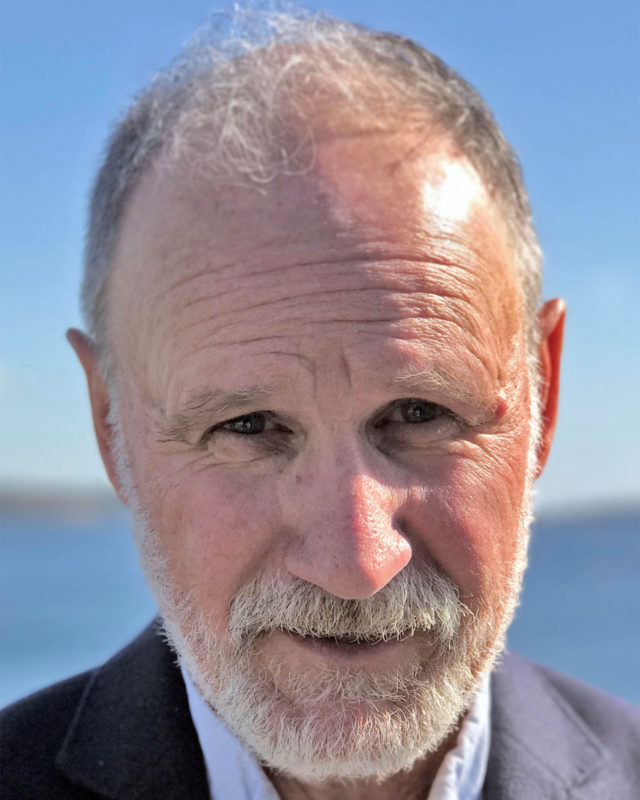

caption

Heritage Trust president Andrew Murphy is concerned about the future of Brunswick Street and its heritage.Many Brunswick Street buildings are registered heritage properties. The one-and-half storey Jonathan McCully House belonged to its namesake, a Father of Confederation, until his death in 1877, while the Fleming House was home to Sir Sanford Fleming between 1867 and 1873. Fleming was influential during the construction of the Intercolonial Railway and is also credited in having established standard time zones. The Little Dutch Church, which was built in 1756, is the second oldest building in Halifax.

The McCully House was recognized as a National Historic Site in 1975, while the Fleming House and Little Dutch Church became municipally registered heritage properties in 1984 and 1981, respectively.

The Heritage Trust has appealed the community council’s decision to the Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board, as they feel the approved development is inconsistent with the Municipal Planning Strategy and has failed to address that inconsistency.

The developer’s initial proposal was a 13-storey development, but this was rejected by community council and later amended to nine storeys and then eight storeys. The initial proposal used more contemporary materials for the exterior, like steel and large glass windows, that were largely at odds with the surrounding buildings. The revised design uses materials like red brick that keep with the streetscape.

The planning strategy outlines objectives and policies for council when making development decisions. According to it, new developments “shall complement or maintain the existing heritage streetscape of Brunswick Street, by ensuring that features … are similar to adjacent residential properties,” including height and height.

Municipal staff worked with the developers to amend the original proposal so it wouldn’t exceed the roofline of St. Patrick’s Church, a non-residential heritage property.

caption

St Patrick’s Church, which is adjacent to the approved development site, was used as a reference for the height of the approved building.This is where the problem is, said Murphy. He said council overlooked a subsection of the strategy when making its decision. He believes the planner used St. Patrick’s Church as a reference for the height of the building, rather than the surrounding residential buildings.

“The law says that the building has to be similar in height to the adjacent residential building, so then it’s a matter of English; is eight storeys similar to three? I don’t think that eight storeys is similar to three,” Murphy said.

According to documents submitted to the Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board by the municipality, it’s the responsibility of planning staff to tell council if a development is consistent with the planning strategy. However, the documents also say there are no policies within the strategy that mandates council needs to bide by staff recommendations.

In evidence submitted by the municipality against the appeal, council “directed staff to consult with the applicant to negotiate changes to the proposed development agreement limiting the height of the proposal to not exceed the roofline of St. Patrick’s Church.”

The documents don’t say which residential property planning staff used as a reference to justify the eight-storey development, given that St. Patrick’s Church is non-residential. Instead, the municipality argues the setback of the development will maintain the heritage streetscape view from the “public realm” or view from the street, but that’s not to say the development won’t be visible.

According to the document, “because of the 60 feet setback from the streetline of the new addition at the rear of the rectory the height as compared to the church tower, although still visible, will be greatly reduced.”

This fails to address planning strategy policies that specifically address the permitted height of developments on Brunswick Street.

caption

The site for the approved development is located behind the old St. Patrick’s rectory.The Signal reached out to municipal communications to explain this inconsistency. However, they were unable to comment, as the case had been filed with the Utility and Review Board.

When asked about the Heritage Trust’s opposition to the development Mayor Mike Savage says heritage is important to Halifax, but didn’t address Brunswick Street directly.

“I think we can do better. There are a lot of people who visit here who want to see heritage — that is an attraction to the city,” Savage said. “It’s one of the great assets of a city, and once it’s gone you don’t get it back.”

Murphy said The Heritage Trust is not against development, but external factors need to be considered.

“We think that the building that is proposed is a fine building and that it’s just its location that’s inappropriate,” he said.

For him, this is why regulations should be followed.

“If I buy a house in a residential area, I can’t have a car auto-body shop. I can’t have a strip club. There are all sorts of restrictions,” he said. “And so, if you buy a building in a heritage area, you should expect that you can’t build towers.”

If The Heritage Trust loses the appeal, Murphy said there is little to stop others from proposing similar developments along Brunswick Street and streets like it. He’s concerned this precedent would expedite future proposals.

He added the appeal has garnered the attention of others involved in heritage projects across Canada and is important for heritage districts in other communities.

caption

St. Patrick’s Church has been a provincial heritage property since 1989.“This is such a blatant disregard for the rules that exist that if they can get this done, there’s not a law in this country that will protect any heritage district. Because if eight is indeed similar to three, then why bother?” he said. “If we lose this appeal, there’s no piece of heritage that’s safe.”

Murphy doesn’t think the community council’s decision was malicious or ill-spirited and is confident it was nothing more than a mistake by planning staff. He noted it was only when The Heritage Trust reviewed the municipality’s planning documents themselves that it became clear on what the drafters had intended.

He’s hopeful The Heritage Trust, council, and the developer can settle the issue without having to go to court.

“There’s no upside for us. We just protect something that we thought was already protected,” he said.