Celebrities in the spotlight

caption

How celebrity journalism moved to page one

On January 2, 2014, former United States congresswoman Jane Harman was set to be interviewed by Andrea Mitchell on MSNBC. The topic: the Privacy and Civil Liberties Board had released a report criticizing the National Security Agency’s collection of telephone records.

Mitchell first asked Harman, who served on the House Intelligence Committee for many years, for her reaction to the news. Harman began answering the question, but was interrupted seconds later. Mitchell said MSNBC needed to cut to breaking news.

“Right now, in Miami,” said Mitchell, “Justin Bieber has been arrested on a number of charges.”

MSNBC then cut to footage of Bieber in court, as the judge read his charges. They later returned to Harman, who continued. But, like when toothpaste is out of the tube, there was no going back on what had happened. MSNBC had cut from a story about the government spying on its own citizens for a story about the arrest of a celebrity.

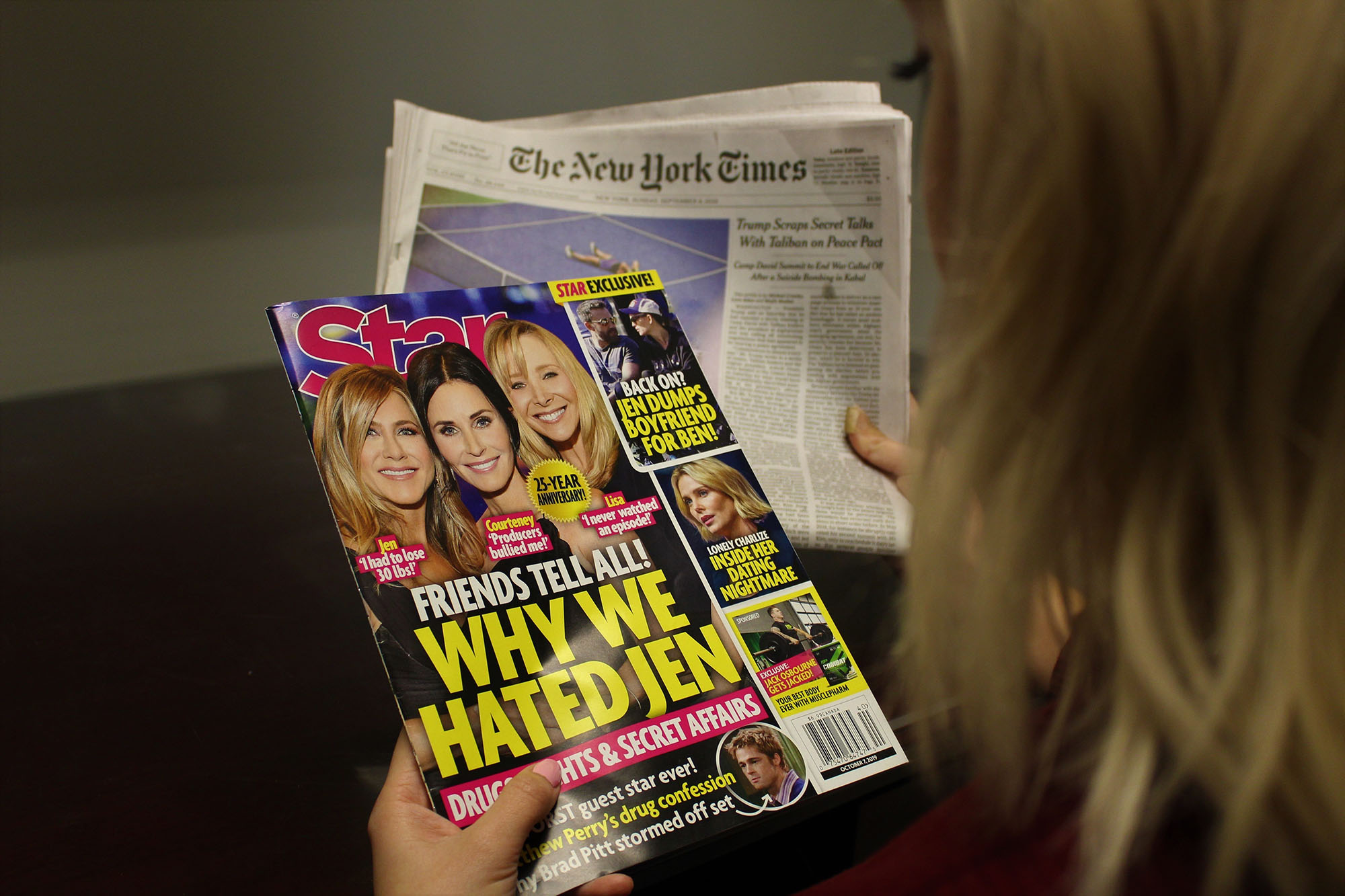

Celebrity news is being covered by major news outlets in Canada and the U.S. more than it was 30 years ago. Stories that found a comfortable home in tabloid newspapers and magazines like the New York Post and People have been moving to dominant mainstream publications such as the Globe and Mail and the New York Times. Why are publications that have prided themselves on their commitment to reporting the most important information now looking to the tabloids for stories?

This is cause for concern. The more these outlets choose to focus on this type of news, the more they run the risk of an important story going unnoticed. Look at how MSNBC cut from Harman.

That’s not to say important stories can’t feature celebrities. Some public figures use their platforms to improve the world or to engage people in issues. Consider Leonardo DiCaprio’s work to save the environment and Taylor Swift’s efforts to help women stand up to sexual harassment. While stories like these may feature a celebrity, they do not fit under the umbrella of “celebrity news”. Celebrity news spotlights the personal lives of public figures. It reports topics that would not be reported for a non-public figure.

“Millions of people get cancer,” said Larry Atkins, a journalism professor at Temple University in Philadelphia. “But it became newsworthy when Alex Trebek got it.”

Driving ratings

When MSNBC cut away from congresswoman Harman for coverage of Bieber’s arrest, people who study journalism noticed. Atkins watched the broadcast live in his home. He was left in disbelief, but understands why the story was covered.

“I’m sure Andrea Mitchell didn’t want to do it,” says Atkins. “Her producers were probably yelling in her ear.”

Atkins says that the thing to remember about celebrity journalism is that if you aren’t covering it, the competition will. This is because celebrity news drives up ratings. Editors and producers are assigning reporters more celebrity stories because it’s what readers want.

And it isn’t just television networks giving more focus to celebrity news. Newspapers are also printing more celebrity stories. Not just in the entertainment section or the obituaries; these stories are dripping onto the front page.

A study of the front covers of three major newspapers (the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star and the New York Times) was done to show how much more this topic is being covered. The front pages of each paper throughout August 2016 were compared to the front pages throughout August 1989. (The months and years were chosen at random.)

While not a scientific analysis, the results give us an indication of the change that has occurred. All three papers had more celebrity stories on the front page in 2016 than in 1989. While front pages a generation ago featured one or two stories each month, these stories are now showing up at least eight times a month.

caption

Why is celebrity news a reliable source for high ratings? According to psychologist Daniel Kruger the answer lies in how our brains are wired.

Why celebrities?

Why are editors choosing to put more celebrity stories on the front page? Why is celebrity news a reliable source for high ratings? According to Daniel Kruger, a psychologist who studies evolutionary biology at the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan, the answer lies in how our brains are wired.

Kruger says people are most comfortable living in groups of 150. This goes back to humans’ early days of living as hunters and gatherers, almost two million years ago. Because of this we can be coaxed into believing that people we see on the news are somewhat relevant to our lives. This ancient part of our psychology still affects us today.

This is why we are so interested in celebrities. Because we are shown details of their lives, we believe they are relevant to our lives — even if we never meet them. We also envy how rich and famous they are. We look to them because we want to make our lives more like theirs.

Kruger believes editors are aware of this. “They’re making use of our psychology to turn a profit.”

The major news outlets are embracing celebrity news because of what William Randolph Hearst figured out over a century ago: the news is may be a public trust, yes, but it is also a business and celebrity sells. People are drawn to celebrity news and major publications feed that interest in the hopes of drumming up new subscribers. It’s no secret newspapers are in a downward spiral due to the rise of digital media; celebrity reporting is a way to draw in more reader interest.

“I’m often horrified by how uninformed people are about what is going on in the world,” Kruger says. “It’s astounding to me that people can be so easily manipulated.”

Celebrity news is on the rise with the newspapers, but how is it being reported? Susan M. LoRusso, assistant director of the School of Journalism at the University of Minnesota, is familiar with how celebrities are covered by the media. Particularly, she has studied how the media deals with celebrity breast cancer disclosures.

In a 2017 dissertation, LoRusso examined how the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Associated Press report on celebrity breast cancer disclosures. LoRusso found 110 separate disclosures printed by at least one of the three organizations between January 2015 and December 2016.

LoRusso identified two ways the media reports on disclosures. She calls them episodic and thematic frames. The former focuses solely on the celebrities’ experience with breast cancer, while the latter reports the same information but puts the issue of breast cancer in the spotlight. LoRusso says the number of episodic stories vastly outnumbered the thematic.

“It was an 80 to 20 split,” said LoRusso. “It really wasn’t surprising.”

LoRusso’s findings show how news organizations are choosing to report on celebrities. Focusing on a famous name can bring in readers.

Tabloids in trouble

While this type of news coverage is on the rise with larger news outlets, the tabloid newspapers that made this type of news so popular are losing readers. Ava Seave, an adjunct professor of business at the Business School of Columbia University in New York, says this is because the larger outlets have begun to cover these stories and because of the internet.

Tabloids depend on newspapers for most of their revenue. Before the internet, they had little competition reporting celebrity news. The internet made it clear how popular celebrity journalism could be.

If the larger outlets cover the same story as a tabloid, and Google is how people search for it, they are more likely to see the larger outlets’ stories. The New York Daily News has dropped in circulation from 300,000 in 2014 to 200,000 in 2017. According to Statista, subscriptions to the National Enquirer dropped from close to 500,000 in 2016 to 244,126 in 2018.

“You have to have some (celebrity news),” says Seave. “If you don’t, no one will come to your site.”

Seave’s thoughts are echoed by Dr. Daniel Hallin, a communications professor at the University of California, in San Diego. Hallin says that because the larger news outlets are covering celebrities more, the tabloids are not special anymore. “The tabloids were distinguished by mixing news and entertainment,” said Hallin. “Their style has become much more generalized.” Tabloids featured celebrity news. Now that everyone has caught on, the news they lived is making them bleed.

The question going forward is this: should the news be based on important events in the world or on what readers want to see? Kruger compares publishers promoting celebrity news to fast food restaurants. He says a fast food company (news organization) would love if people only bought salad (hard news). But they know most people want hamburgers (celebrity news).

“They know what sells,” says Kruger, “even if it is not the healthiest choice.”

About the author

Jakob Postlewaite

Jakob Postlewaite is a fourth-year journalism student at the University of King's College. He has worked as a columnist and reporter for the...