The Beatles

Dalhousie prof solving music problems with math

Jason Brown is working on a new music authentication technique

caption

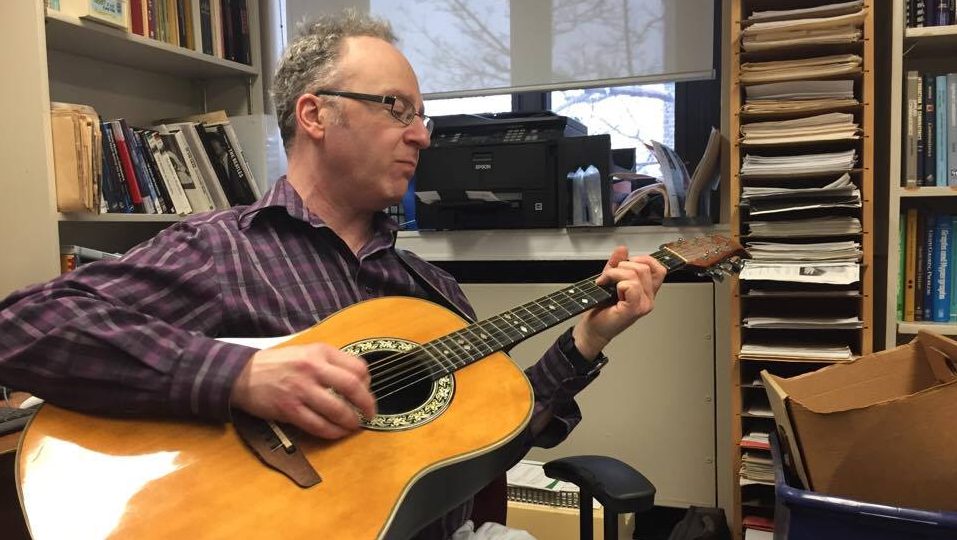

Professor Jason Brown playing guitar in his office.

caption

Professor Jason Brown playing guitar in his office.When Paul McCartney and John Lennon were in The Beatles, they published their songs under a joint partnership. When they were later asked about which of them actually wrote each song, they agreed on all the songs but one: “In My Life.”

Both agreed that the lyrics were Lennon’s, but they couldn’t agree on who wrote the music. Rolling Stone calls it “a dispute that will never be resolved.”

Just don’t tell Jason Brown. Related stories

Brown is a mathematics professor at Dalhousie University. He is working with Harvard University statistician Mark Glickman on a new musical authentication system that will solve authorship disputes using math.

“When you have a piece of music where two or more composers claim to have written a song, how do you determine who likely has written the song?” Brown asks.

Brown says the solution is similar to successful techniques for determining the author of a piece of writing. They build a database of authors’ work. Once they have the data, they mine them for patterns. They then compare these patterns to anonymous works to find a match between the patterns in an author’s known work and the anonymous works.

But they also face challenges unique to music.

“Music is a slightly different kettle of fish,” Brown says. “It’s a much smaller alphabet in terms of chords.”

Brown and Glickman first met at a the Science Atlantic conference in Nova Scotia in 2013. Glickman is known for ranking the world’s chess players, which he spoke about. When Brown found out Glickman was also a musician, they quickly bonded. They do most of their work together over Skype and each contribute an important part to their project.

“As a statistician, (Glickman) brings a knowledge of statistical models,” says Brown. “It’s unlikely that you’re going to find a definitive answer … to some extent anyone can write any song.”

Even if a composer follows similar patterns, he or she might break from those typical patterns in any given piece. That’s why Brown and Glickman can, at best, do a statistical analysis to decide the likelihood a certain composer wrote a certain song, but its not a definitive answer.

For his part, Brown brings his own musical background and knowledge, plus a variety of mathematical techniques to mix in with the statistics.

Brown says he can’t explain too much about this project until it’s ready, which he expects will be six to eight months.

“Until the data is clean, I’m not comfortable giving any definitive answers because things may change a little bit,” he says.

In the last couple of years, many famous artists have been accused of plagiarism–most notably Led Zeppelin for “Stairway to Heaven.” The band was eventually cleared, but Brown and Glickman’s project would theoretically be able to help in similar disputes.

caption

Brown strumming alongTwo passions

This isn’t the first time Brown has been inspired by the foursome. Growing up, music was his first passion because of The Beatles.

“I was the kind of student that would only practise the piano for a half-hour before my lesson each week, trying to fool my teacher,” he says. “But when I heard a Beatles record, everything changed. I had never played guitar before, but I immediately gave up piano and started teaching myself guitar. And instead of practising a half-hour a week before my lesson, I was now practising myself and teaching myself guitar eight to 12 hours a day in the summer.”

For a while, Brown focused on music. He played in bars and clubs, on TV and in concerts. He even played for thousands of people during the Calgary Stampede, but eventually he switched to something else.

“I moved into mathematics, my second passion, and that became my career,” says Brown.

Mixing math and music

After some time working as professor, he found a way to use both his passions in a single project.

“In 2004 I brought both of them together with a mathematical study of how The Beatles played the opening chord of ‘A Hard Day’s Night,’ which was a mystery up to that point,” says Brown.

Brown used a mathematical tool called Fourier Transforms to decompose the chord’s sound waves into basic parts, and then analyzed the results to determine what notes made up the mystery chord.

He realized it was mostly an open chord on George Harrison’s new 12-string guitar, and the previously unaccounted for notes came from a piano that their producer George Martin played.

Since then, Brown has found more ways to meld math and music. He has written articles on the blues chord progression, George Harrison’s edited solo on “A Hard Day’s Night” and the famous edit in “Strawberry Fields Forever” (page 16).

‘A Million Whys’

Brown took this combination to another level when he wrote a song inspired by mathematical patterns he gleaned from The Beatles’ early work.

The resulting piece was called “A Million Whys.” There were instances in the song where Brown imitated The Beatles’ style, and others where he purposefully broke from their mould.

“I have patterns of threes at the very beginning because I know George Harrison loved to do that,” says Brown.

He also started his song on a beat other than the first beat.

“The Beatles sometimes had opening of songs where they didn’t start on beat one even though they knew the listener assumed they started on beat one,” he says. “And it would be a little joke later on because everyone would be fooled a little bit until they could figure out where beat one was.”

To purposefully go against The Beatles’ model, Brown made the bridge the longest part of his song. Typically, The Beatles typically made it the shortest part of their songs.

The Wall Street Journal came up to film Brown performing the song with his band, which you can watch here.