Diverse voices on campus

caption

Host Randy Hamilton broadcasting the Right Deadly Radio Show on CKDU on Oct.3.CKDU's Radio of culture and connection

“Hi everyone, welcome to the Right Deadly Radio Show here on CKDU 88.1 FM. I’m your host Randy Hamilton, and if you’ve listened to this radio, you already know that, and if you haven’t, I’m gonna tell you anyway,” intones a deep male voice over a background of subtle digital crackling.

Randy Hamilton hosts his one-hour radio show three times a week from a quiet, dim home studio, with no distractions other than his large white dog who occasionally paces in the room next door.

Shortly after Hamilton’s Indigenous radio show ends on Thursday evenings, Larry Steele, a French professor at Mount Saint Vincent University, wraps up his classes for the week and rushes to his home in Halifax’s North End, where his wife is making dinner. He heads straight to his second-floor study to adjust his microphone for his French-language radio show, Trois Beaux Canards.

With the kitchen radio tuned to Steele’s program, the house fills with the aroma of dinner. After he introduces a song, Steele races downstairs to check his program’s reception, briefly dances with his wife, and then returns upstairs to continue broadcasting. He has done his radio shows for an impressive 26 years.

“I like to interview people. It’s often musicians. We talk about how they got to where they are and what they like about music,” Steele said. “I’ve always loved poetry. I’ve always loved song. It’s so fantastic. It’s so beautiful. I just wanna get out there and share it and play it.”

The Right Deadly Radio Show and Trois Beaux Canards are two of CKDU’s cultural programs. CKDU, Dalhousie University’s campus radio station, hosts a total of six cultural shows, five in languages other than English. Hosts broadcast from their own homes, with the signal transmitted to, and broadcast from, the station in Dalhousie’s Student Union Building to the entire Halifax region.

The National Campus and Community Radio Association (NCRA) conducted a language review and found that over 65 different languages, including four Indigenous ones, are broadcast on its member stations. Many stations have programs in 10 or 15 different languages.

“We’re a place where almost anybody of any background can come in with knowledge or no knowledge of radio and the job of the radio station is to train people to know and to become broadcasters,” Barry Rooke, the executive director of NCRA, said. “You can’t do that at any commercial radio station. It’s not what their job is, they’re interested in making money.”

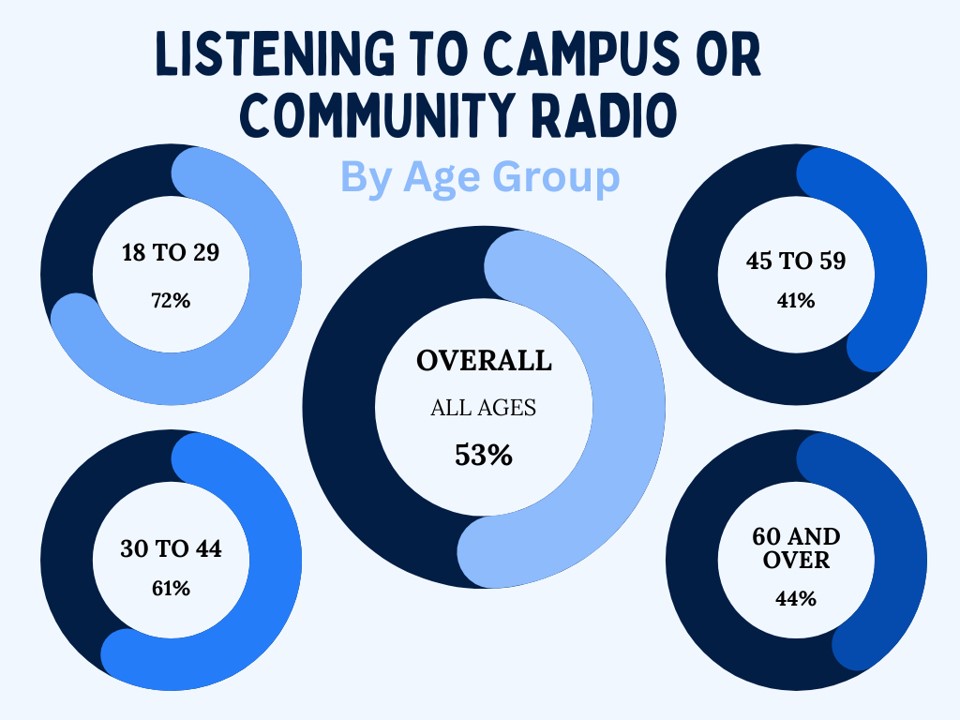

Data from NCRA indicates that the primary audience for campus or community radio is usually male between the ages of 18 to 29. Most of these listeners were born outside of Canada. Nearly half of these listeners identify as part of a visible minority.

Brian Fauteux teaches popular music and media studies at the University of Alberta and is the author of Music in Range: The Culture of Canadian Campus Radio. He says that the media landscape has become fragmented and transitional due to layoffs in both traditional and new media outlets. As a result, some broadcasters may seek inspiration from campus radio.

“It’s a good moment for looking for new ideas or for ideas that have been in place for a little while and thinking about what works in terms of diversifying media and news reporting,” Fauteux said. “If we’re thinking about music programming as well, I think that campus radio has been a very innovative space for thinking about how to program from a variety of musical styles and other media outlets sometimes can look to that as a model.”

Fauteux said that campus radio is more likely to develop diverse cultural programs because it relies primarily on volunteer work.

A commercial station prioritizes its listener base and securing advertisers to stay in business, but for campus and community radios, ad-supported material is not the goal.

“The goal is to diversify the airwaves to have the voices of people in the community on air,” Fauteux said. “It means that people who are bringing something unique and diverse to the overall media landscape are welcomed and encouraged over something that you would hear on commercial radio already.”

The NCRA survey shows that the Atlantic region boasts the highest proportion of campus or community radio listeners.

As the largest campus radio station in Atlantic Canada, CKDU airs Indigenous, French, Pidgin-English, Arabic, Eritrean and Farsi radio shows.

“It is easier for us to use this same language to convey our culture to this place. You cannot separate culture and language. They go together,” said Donatus Owa, the host of Elders Korna, a pan-African broadcast in Pidgin English on CKDU.

Pidgin English mixes English and different African languages. For that reason, Pidgin English is different in Nigeria, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon, but the dialects are close enough that people from these countries can generally understand each other.

Owa hopes the radio show will help future generations of African Canadians understand the language of their parents and grandparents.

“When they grow up, they will realize that this is the language that my dad speaks at home and I hear it on the radio,” Owa said.

“As a campus and community radio system, we just want everyone to feel represented on the campus or in the community,” said Kheaven Brasier, CKDU’s program director. “If you want to do a show and the language is not in English, we are very supportive of that. I’ll do everything I can to get that show going.”A person smiling with arms crossed

Enzo Le Doze, who listens to Steele’s French radio show, is thankful for CKDU’s cultural and multilingual programming. Doze, who is from France, says the show helps him stay connected with French and binds him with the local community.

“If I really needed a show in French, I could find it easily in Canada but the fact that it is from Halifax makes it more relevant to me, and even just the ads on CKDU are relevant because it’s local shops that I might visit,” Doze said.

Compared to large commercial radio stations that serve a wider range of people and issues but have less flexibility, campus radio builds connections with small communities, Brasier told The Signal.

“We have the opportunity to be hyper local. We have the opportunity to bring in community members that have something to say for their community. They can use CKDU to lift that voice up to broadcast and to be heard by their communities,” Brasier said. “It’s up to CKDU’s staff to keep reaching out and to keep trying to make diverse folks feel invited in through where we do our outreach, how we do our outreach, who are speaking to, what we’re playing on the radio.”

One year ago, in response to public and listener feedback, CKDU approached Hamilton, a Mi’kmaw audio engineer and musician, to create a new Indigenous show.

Hamilton’s situation is unique in that CKDU pays him a salary, while it doesn’t pay other hosts. If the grants for Right Deadly Radio Show run out, Hamilton’s time on the CKDU airwaves will most likely end. Funding comes from the Dalhousie Student Union, donations and advertisements. “Volunteers are always the preferred way of doing it, but sometimes volunteering isn’t really enough,” Brasier said. “With the current budget, it’s really hard to pay people to go on the radio.”

Right Deadly Radio Show is the newest cultural program on CKDU. It airs three times a week while most other shows are only once a week.

In his broadcasts during the last week of September, Hamilton shared his information about Truth and Reconciliation Day on his show. He guided people to the event and encouraged non-Indigenous people to join in commemorating the day.

“I would hope Indigenous people are listening [to my show] and I know I do have some, but I think it’s mostly non-Indigenous, which is good too, because it could be a learning experience,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton concludes his show with a piece of music by an Indigenous musician. As he switches off the microphone, he hears a key turning in the front door — his children have returned from school. The children rush into the house, disrupting the peace.

A few hours later in Halifax’s North End, Steele removes his headphones and goes downstairs to have a relaxed dinner with his wife. This time he doesn’t have to hurry back to the microphone on the second floor when the music is about to come to end.

About the author

Xixi Jiang

Xixi Jiang, who often goes by Jacky, is from China. She’s a fourth-year student in BJH program at the University of King’s College.