Erasing the media from social media

caption

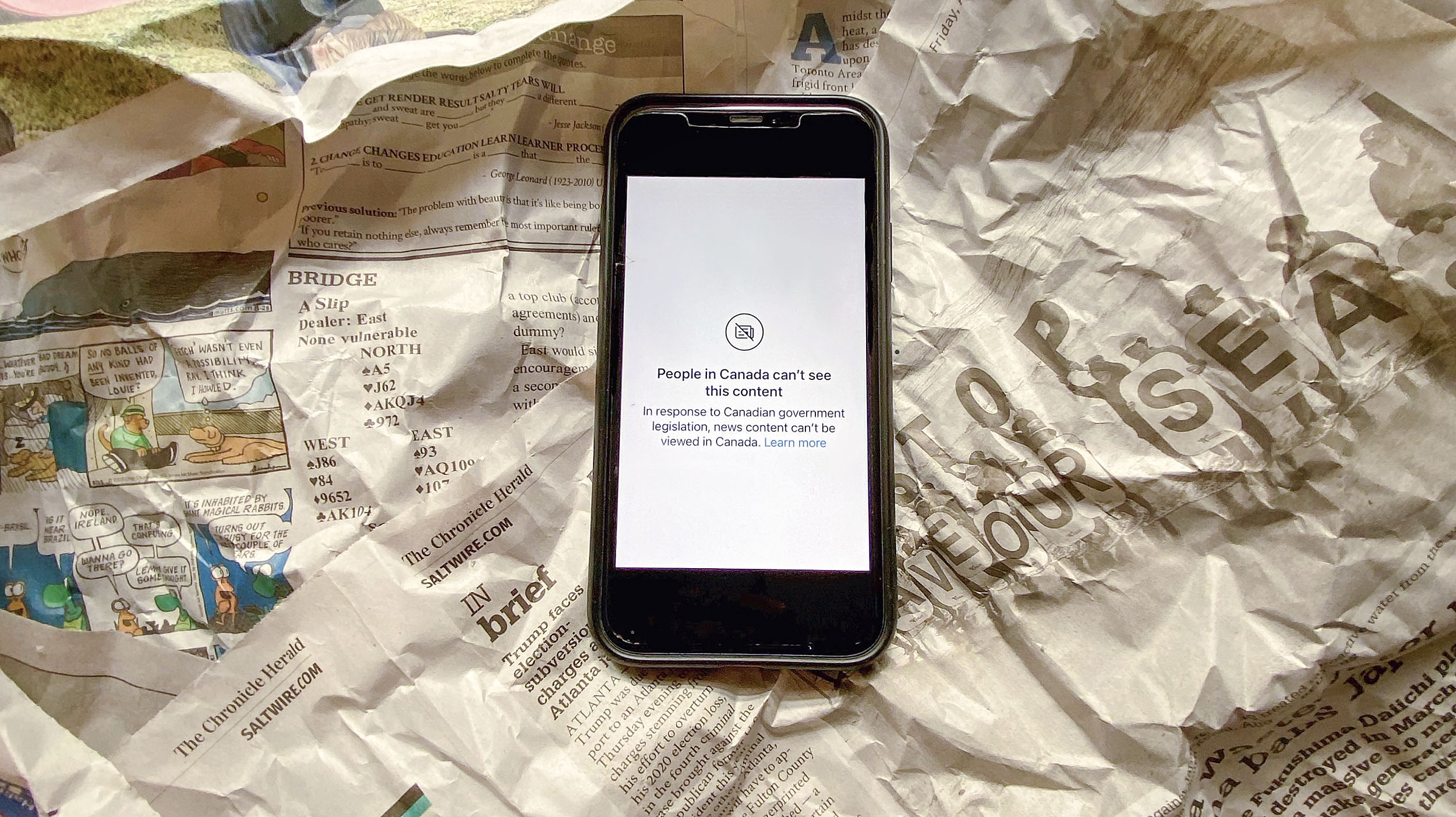

A phone with a blocked news site sits on a crumpled up newspaper.How Bill C-18 is harming student journalism and Canadians’ access to news

Editor's Note

Shortly after this feature story was written, the Canadian government and Google reached an agreement that will see Google pay Canadian news organizations $100 million a year, indexed to inflation.

Sammy Kogan was setting up for a photoshoot in the office of Toronto Metropolitan University’s independent student newspaper, The Eyeopener. Chunky grey sweater sleeves pushed up to his elbows and camera gear strewn about the room, Kogan was interrupted by an emergency alert on his cell phone.

The alert warned of a man carrying an axe on the TMU campus. Kogan knew he had to cover the story.

“Negin, there’s a man with an axe, I’m going,” Kogan said, popping his head around the corner of the office to alert Negin Khodayari, The Eyeopener’s editor-in-chief. Quickly, Kogan scooped up what cameras he needed and dashed out of the office and across campus.

The Eyeopener published the story online later that day, but the paper was unable to share it on social media. Meta, the parent company behind popular social media sites Facebook and Instagram, has blocked Canadian news in response to federal Bill C-18. As a result of the block, the story was only able to be uploaded to The Eyeopener’s website. “There’s always this kind of underlying stress, because yes, we will be able to get around Meta’s ban,” said Kogan. “But one thing that I’m very, very concerned about, and I think a lot of people at (The Eyeopener) are as well, is Google’s response.” Related stories

Bill C-18 has led Meta to block the posting of links to news content on Instagram and Facebook pages and Google has begun to do the same. Student news outlets are losing audience reach since it’s harder for them to share their work, and with Google implementing its own ban, it has become even harder.

What is Bill C-18?

The purpose of Bill C-18, or the Online News Act, is to compel social media platforms to compensate news organizations for the news links posted by the platforms’ users. The bill requires sites like Facebook, Instagram and Google to pay for news stories that appear on their sites.

Between 2008-21, 450 news outlets closed across Canada, but Canadians are still consuming news, with a majority accessing news online. When a news article is accessed through social media, the revenue from the ads in that article go to the social media sites, not the news outlet. Essentially, these sites get paid for providing content that is not theirs.

In 2020, online ad revenues in Canada were $9.7 billion; Google and Facebook had a combined share of 80 per cent of these revenues. What Bill C-18 requires is that digital platforms compensate news outlets for their content.

Since the rollout of Bill C-18, Meta has also cancelled existing deals with Canadian news outlets, and Google is expected to follow suit. In October, after a month-long public consultation about the drafted regulations, Google said in a statement that there were fundamental problems with the legislation.

Michael Geist, a lawyer and digital law professor at the University of Ottawa, said it’s unlikely that Meta will return to news in Canada, at least as long as the legislation exists in its current form. “I think they’ve been pretty clear that they believe that the legislation is deeply flawed,” said Geist, “that payments for links that are largely posted by publishers themselves is something that they ought not to pay for, if anything, they’re providing value by driving traffic.”

Lost audiences

The Canadian news ban on Meta sites doesn’t just affect large media outlets—it’s harming small independent media outlets like student news sites that don’t have the clout to make deals with Meta and Google for their content to be shared.

Across Canada, student news sites have seen their audience reach drop drastically since Bill C-18 was tabled. At TMU, fourth-year students have seen a 40 per cent drop in traffic on the stories they publish as part of their coursework, according to the course professor Angela Misri. “We are still, as part of our teaching, incorporating marketing our stories after they’re done, with social media. We still think that’s important learning because we really hope this isn’t going to be happening to us still in six months to a year from now,” said Misri. “We hope that we will be able to come back to actually accessing our audience online.”

Student news outlets like those at TMU and the University of Victoria, which depend heavily on social media to reach their audiences, the ban has hit hard. Rowan Grice, the manager of the University of Victoria’s student run radio station, told the Times Colonist that his station’s audience reach on social media has plummeted more than 90 per cent.

The Martlet, the University of Victoria’s independent newspaper, has also experienced a drop in views and community reach. The Martlet’s website doesn’t allow comments on stories so, prior to Bill C-18, interactions with its audience occurred mainly through Instagram and Facebook. Now that the bill has been implemented, articles published by The Martlet that would have historically generated a lot of traffic aren’t shared or interacted with like before.

“All I can see now are the page views,” said The Martlet’s editor-in-chief, Ashlee Levy, “which is definitely not the same as seeing people sharing it and commenting on it and things like that, so there definitely isn’t as much interaction with our content going on.”

Consuming news in new ways

Bill C-18 has also changed the way journalists build a platform and online presence. “It’s definitely changed the way that journalists are able to communicate with, I guess, the whole of Canada, and it’s changed the way that we can consume news and share news as student journalists.” said Jordyn Haukaas, the student editor of Nexus, the student newspaper of Camosun College in Victoria.

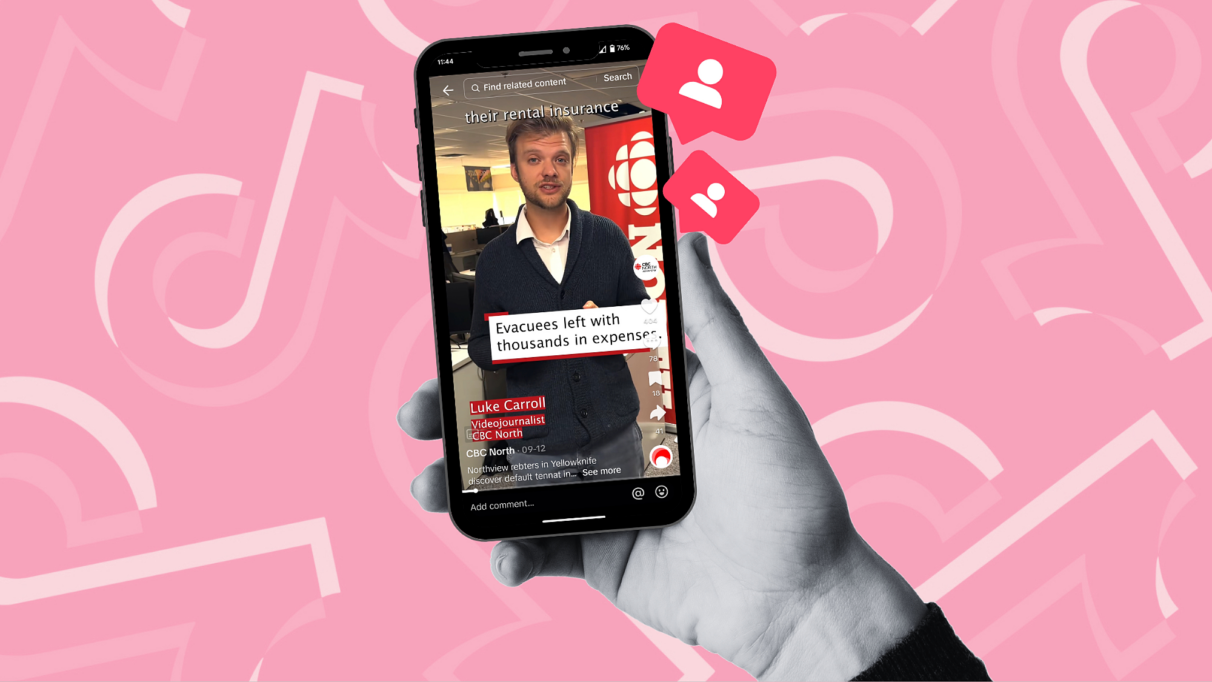

To share their work now, journalists at Nexus are going analogue — they’re heading out onto campus and talking to people. “It feels very strange in our day and age, but we’ve been actually going out and, like, talking to students and even handing them papers or trying to set up booths,” Haukaas said. Meanwhile, back at the University of Victoria, The Martlet has begun publishing more newsletters and is working on bolstering its TikTok presence.

X, formerly known as Twitter, has always been a major platform for journalists to share their work and make connections. However, since Elon Musk purchased X in 2022, users face new obstacles. Now they need to be verified to connect with other verified members. For this to happen, users need to be willing to pay a subscription fee of $15 a month.

Google is another obvious avenue for student journalists to share news and find sources, but that resource could also disappear if negotiations between the Canadian government and Google fall through. Small, independent media outlets are already taking a hit because of the Meta ban, but losing Google would be an even greater wound for Canadian news.

“It’s one thing to remove links from social media sites, it’s quite another to have them removed from search results,” Geist said.

With the block of Canadian news on Meta sites, many news outlets are moving to different platforms like TikTok, Molly MacNaughton reports.

While negotiations with Google are ongoing, organizations like Canadian University Press (CUP) are in communication with Pascale St-Onge, the Minister of Canadian Heritage.

CUP is encouraging journalists across Canada to speak out about how this bill is affecting them. “The only thing we can do right now to advocate for ourselves, is to reach out to members of Parliament,” said CUP president Andrew Mrozowski. “Reach out to folks at the Ministry of Heritage who are the ones who are pushing for this bill.”

Haukaas encourages her peers to do the same: “I think there’s nothing more powerful than your own story. And sharing that with the powers that be could hopefully open their eyes to how student journalists from across Canada are seeing this impact their work.”

Looking forward

So, what does the future look like for media outlets like student-run newspapers?

“I can give you the rose-coloured glasses version, which is that people start to value news so much that they go and seek it out,” Misri said. “The audience has become really lazy in that they get content pushed to them at all times and they don’t have to go looking for it.” Her hope is that people will start paying for quality journalism and making an effort to go find news because they care to know what’s going on in their communities.

Levy agrees. “It’s going to be in the hands of the readers, it’s going to be their responsibility to actively seek out news and actively support journalists and media platforms including smaller independent newspapers.”

About the author

Kayleigh Stevens

Kayleigh Stevens (she/they) is a fourth year BJH student at King’s. They have always had a passion for writing, reading and being indecisive....