Mental Health

Feds offer substandard wages for refugee interpreters

Disagreements over federal reimbursements delayed refugees from getting mental health care

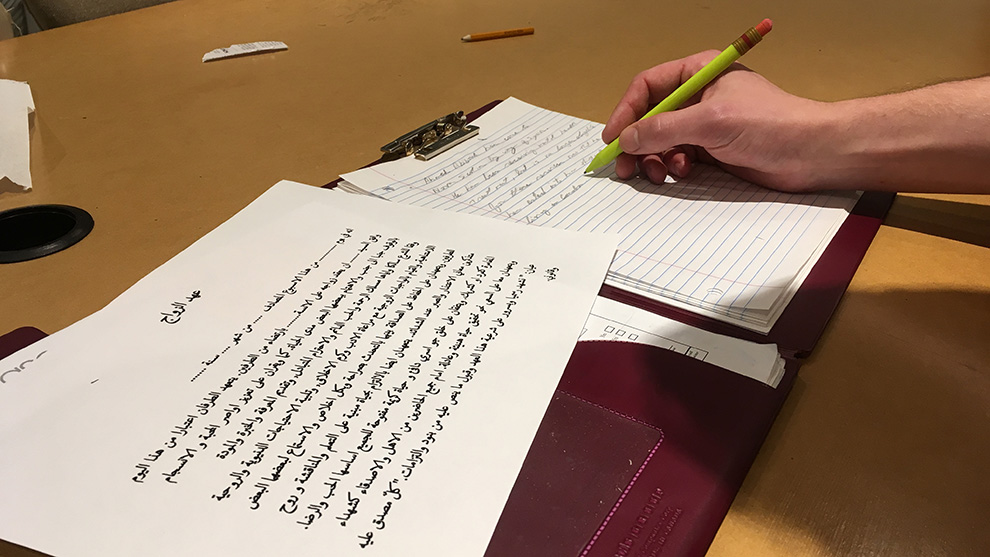

caption

Interpreters provide a valuable service for refugees

caption

(Staged Photo) Interpreters and translators provide valuable services.This is the second half of The Signal’s two-part series on refugees’ access to mental health care.

Syrian refugees needing mental health care have had their treatment delayed by months because of wage disputes with specialist interpreters, advocates say.

Carmen Moncayo, Community Wellness Program Coordinator at Immigration Services Association of Nova Scotia (ISANS), says “it has been very challenging to coordinate the proper care.”

She says part of the problem is logistical. Getting refugees together with properly-trained psychologists capable of treating depression, anxiety and PTSD has proven in and of itself to be a difficult process — but a bigger obstacle has come from arranging interpretation services.

Refugees in Canada get 12 months of health care under the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP), which allows them to receive private therapy treatment from psychologists if they are considered to have serious mental health problems.

A spokeperson for Canada’s immigration department, Lindsay Wemp, says the health program provides 12 months of “supplemental coverage,” including ten treatment sessions from “clinical psychologists.”

But for the past year, therapists say, they have been prevented from treating as many refugees as they would like.

They say a large obstacle in this process has been trying to hire interpreters who are willing to work for a government wage that is far below their standard rates.

Nathalie Schofield of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada told The Signal that “if interpretation is needed during the treatment,” the IFHP will “reimburse $28.95 per hour” for these services.

Issam Khoury, a member of the Association of Translators and Interpreters of Nova Scotia, says he and some of his colleagues were “contacted to do this work,” but when offered the negligible rate, they “had to decline.”

Merek Jagielski oversees interpretation and translation services for ISANS. He defends the decision made by Khoury and his colleagues.

Jagielski says it’s an issue of recognizing “the complexities of this type of interpretation” and offering fair compensation.

“Interpreters and translators, especially those working with psychologists and refugees in this sort of work, need to have specialized skills and training,” he says.

Jagielski explains that under the IFHP, interpreters would receive “no other source of funding” for their work other than the reimbursement, which is not a competitive rate for their services.

For instance, the Nova Scotia Interpreting Services website shows their rates start at $50 an hour for in-person interpreting. This figure was confirmed by someone who answered their phone.

These rates are comparable across the country.

Shanta Singh of Multilingual Community Interpreter Services in Ontario told The Signal that their average rate for this type of work begins at $52.80 per hour, with additional travel costs included.

The Winnipeg Regional Health Authorities Language Access Interpreter Services Coordinator, Gracie Liu, says medical interpreters in her province “are paid a minimum of $50 an hour.”

In British Columbia, Bessy Ferris of Mosaic Interpretation and Translation Services, says “medical interpreter rates range from $50 to $75 an hour.”

Jagielski says, interpreters are well within their rights to decline the reimbursement rate because “mental health interpretations” are such an advanced form of the service.

“I know that initially when we approached senior interpreters, they felt concerned about the amount of work required, which was a huge amount,” Jagielski says. “So there were concerns expressed regarding that this is not fair compensation for this type of work.”

Interpreter setbacks delayed the mental health treatment of refugees by months. Because of these issues and other bureaucratic complications, “it wasn’t until October that we were able to start seeing Syrians,” says Lesley Hartman, a local psychologist who has treated refugees with depression, anxiety and PTSD.

These hurdles — combined with Canada’s one-year time limit on refugee mental health therapy, which was previously reported by The Signal — mean that Syrians who were once eligible for a critical health service are no longer able to receive funding for such treatment.

ISANS ultimately found interpreters who would be willing to work for a dramatic pay cut, and started training interpreters in the summer.

This left a small window of opportunity to give patients their ten sessions of federally-funded treatment.

If refugees weren’t accommodated within this time frame, then “the whole year would have gone by without refugees even walking through my door,” says Hartman.

Hartman says “it almost feels like the government doesn’t want people to get mental health access.”

Hartman says she lauds the government for “opening its doors the way they have.” But, she says, “we have a responsibility to provide refugees with the services they need to make their transition healthy.”