Fighting the ‘unforgiveable sin’ — plagiarism

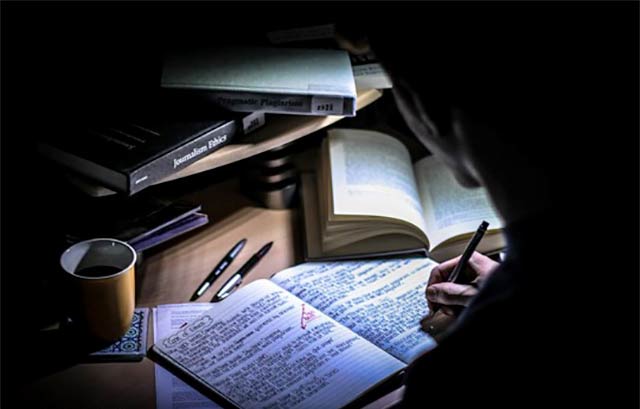

caption

The dark corner of plagiarism.Everyone hates plagiarism, yet more cases are discovered

Plagiarism is a dirty word for journalists. It’s shameful, desperate and unethical, and many newsrooms assume journalists know better.

The sad truth is, some don’t.

The reasons journalists plagiarize vary. From being under pressure in reaching a deadline, or plagiarizing once and it becoming an addiction, the industry has heard it all. The most common excuse for plagiarism is: it was an accident. A journalist accidentally stole another writer’s words, it fit the story perfectly, and the piece was finished just in time.

The excuse of not knowing better is sometimes accepted. With brief ethics guidelines on plagiarism and attribution, and minimal education in some newsrooms on what constitutes plagiarism, journalists often get away with such excuses. Who’s to say a journalist didn’t know better if there is no proof showing otherwise?

Ten years ago the Jayson Blair scandal shocked the journalism world. It was a low point not only for the New York Times, but for journalists across the globe. More than 35 articles written by Blair contained plagiarized or fabricated information. The time it took to catch Blair in his deceptive ways was even more humiliating – his lies and betrayal could be traced back to his late 1990s college years.

Every time a journalist is caught plagiarizing, the trust between the public and the media dies a little more. The bigger the scandal the greater the loss. In the case of Jayson Blair, trust in journalism took a serious hit. There has been time to recover from this setback, to regain lost trust and change the way plagiarism is treated in newsrooms.

Unfortunately, the humiliation for journalism continues. In 2012 alone there were 31 public plagiarism and fabrication scandals – the highest since 2006, which had 27 cases. (Keep in mind these are only the scandals made public, and many plagiarism matters are handled privately.) Among this number were three serial fabricators and three serial plagiarists.

A call was finally made for change. Craig Silverman, founder and editor of the blog Regret the Error, who joined the Poynter Institute in late 2011, challenged the industry to investigate plagiarism in journalism.

Silverman coined the term “Summer of Sin” to describe the summer of 2012, when ten plagiarism scandals occurred in four short months. In his article Journalism’s Summer of Sin marked by plagiarism, fabrication, obfuscation, Silverman called for journalism’s leading professional organizations to come together and battle plagiarism.

Teresa Schmedding, president of the American Copy Editors Society, answered Silverman’s call and began assembling volunteers for a national summit to fight plagiarism and fabrication. With this summit came a free e-book, Telling the Truth and Nothing But. The e-book highlights the problem of plagiarism, suggests plagiarism policies and contains information on proper attribution.

“It is kind of a good PR move for us as journalists to all be together and say ‘we don’t stand for this’,” says Schmedding. “We went to this summit, we participated in this book, and these are the ethics we stand by.”

According to Roger Fidler, program director at the Reynolds Journalism Institute of the University of Missouri, the e-book was posted on the institute’s website on April 1, 2013, and has been downloaded 2,330 times.

Since the plagiarism and fabrication summit, have any newsrooms changed the way plagiarism is handled?

“Not that I’m aware of,” says Craig Silverman.

A 2012 study conducted by the research company Ipsos shows only 31 per cent of Canadians trust journalists. Honesty and transparency with readers needs to be a priority. Plagiarism policies and education on proper attribution may help people turn back to journalism.

Silverman says newsrooms “…need to be really transparent about what they discover” when it comes to plagiarism. “There have been cases where an organization won’t actually say what item has been plagiarized, and from where, or how many times.”

According to Silverman, the most common line heard from newsroom leaders when plagiarism occurs is “this is an internal personnel matter and we will be dealing with it appropriately.’ The bottom line is that we don’t accept that excuse from other organizations. The idea that newsroom leaders would offer that up in these situations is really hypocritical.”

Jonathan Bailey, founder and editor of the webpage Plagiarism Today, a New Orleans website devoted to raising awareness about online plagiarism says, “It’s important to be transparent. The problem is when the newspaper doesn’t open up and say ‘this is what’s going on,’ there’s a tendency for the public to think they are protecting the reporter.”

Sloppiness is a guilty plea. It’s not an excuse.

– Steve Buttry, Digital Editor

Plagiarism is complicated. Jan Leach, a member of the plagiarism summit, says when creating the e-book a group of people worked solely on the definition of plagiarism. “We struggled with the idea that plagiarism in one case may not be plagiarism in another, the idea of self-plagiarism and online plagiarism,” says Leach. “We really tried to be as inclusive as we could.”

Dr. Norman Lewis, of the University of Florida, says that in creating his study Paradigm Disguise: Systemic Influences on Newspaper Plagiarism he was surprised by the malleability of the plagiarism definition. Lewis argues “language changes significantly” when discussing plagiarism, and newsrooms only publicly use the word plagiarism when the journalist in question has been fired.

The New York Times ethics code refers to plagiarism, at one point saying, “Staff members or outside contributors who plagiarize betray our fundamental pact with our public… we will not tolerate such behavior.”

The Los Angeles Times ethics code is no more in-depth, saying, “We report our own stories, but when we rely on the work of others, we credit them.” The word plagiarism is left unmentioned.

The Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ) ethics code says, “While news and ideas are there for the taking, the words used to convey them are not. If we borrow a story or even a paragraph from another source, we either credit the source or rewrite it before publication or broadcast. Using another’s analysis or interpretation may constitute plagiarism, even if the words are rewritten, unless it is attributed.”

Paul Schneidereit, a reporter at the Halifax Chronicle Herald and a member of the CAJ board, says “Maybe it could be clearer… I think there is an assumption that those who are reading it understand what it means. A member of the general public might not.”

Schneidereit says the CAJ recognizes plagiarism is important. The volunteer-run organization is “open to revising or offering new ways for journalists” to conquer this “complicated topic.”

Many newsroom ethics codes lack information on plagiarism. Journalism school guidelines are often much more descriptive. Many journalism schools also have a mandatory ethics class, teaching students how to properly attribute a source and what exactly constitutes plagiarism.

Ivor Shapiro, chair of the Ryerson School of Journalism and an ethics professor, says it is important to “…make sure the students understand how damaging it is to be suspected of plagiarism. Why do we have to spell it out? Well, I guess we have to spell it out because it’s complicated.”

Shapiro says that although there are high numbers of professional plagiarism cases, he hasn’t seen an increase in students caught plagiarizing. “I haven’t the slightest doubt that some of our students plagiarize, I’m sure they do. Are we catching them? No more than before.”

The School of Journalism at Arizona State University enforces a one-strike policy. Any student found guilty of academic dishonesty fails the course and is kicked out of the school with no exceptions.

Ryeron’s Shapiro is uncomfortable with this policy. “You know, an 18- or 19-year-old person takes a shortcut, it’s serious, it’s important… but they don’t need to have their lives ruined by it.”

The e-book released with the plagiarism and fabrication summit recommends all journalism schools adopt the one-strike policy. “By the time an undergraduate student is accepted into the journalism major, zero tolerance should apply.” The e-book encourages newsrooms to choose between a one-strike policy and a graduated scale of punishment.

Why is the e-book tough on students? Craig Silverman, a member of the plagiarism summit, says, “There is a natural tendency to look and say ‘Okay, so how are these people trained and what habits do they form early on in their career?’”

When plagiarism is found in a newsroom, it is common for the accused journalist to say they didn’t know they were plagiarizing.

Dr. Lewis at the University of Florida says few people who plagiarize are actually confused about what plagiarism is. If you’re caught red-handed, you have two options. “You can either confess… in which case you know you’re going to get fired,” says Lewis, “or you can say, ‘gosh, I didn’t know that was plagiarism’.”

He adds, “we shouldn’t be surprised that people who might like to protect their income, dignity or their self-esteem resort to the only response they’ve got: ‘I didn’t know’.”

Digital First Media, the company managing MediaNews Group and 21st Century Media, has taken a step forward in the battle against plagiarism.

Steve Buttry, digital transformation editor for Digital First Media, says a plagiarism quiz was developed in late 2011 or early 2012 after the group suffered two incidents of plagiarism.

“The quiz helped us identify some training issues. It helped us educate people about what they didn’t know, while documenting that people had an understanding of what plagiarism is,” says Buttry. “It is a firing offence in our company.”

Buttry calls for a no excuse culture. The excuse of being sloppy and forgetting to attribute is “…bullshit 90 per cent of the time. Even sloppy people know when their work requires them to be careful.”

He adds, “sloppiness is a guilty plea. It’s not an excuse.”

Teresa Schmedding of the American Copy Editors Society believes the quiz is “an excellent example… I’m working on the same thing here.”

A quiz is not the only way to prevent plagiarism in a newsroom. The summit e-book also encourages plagiarism detection software, outlines fact-checking methods and suggests having annual meetings with newsroom staff to talk about plagiarism.

The creation of the plagiarism and fabrication summit, the free e-book and the quiz are all steps in the right direction. Plagiarism is a problem for the entire industry.

Top leading journalism organizations and journalists came together to create the e-book, which is full of methods and guidelines on stopping plagiarism. The fact that many newsrooms have not yet adopted the policies suggested is discouraging.

As journalists, credibility is the base of our Jenga tower. The point of the Jenga game is to see how many pieces can be removed before the structure falls apart. As pieces are removed, the structure becomes unbalanced. Many who play Jenga avoid disrupting the stability of the base – taking away these pieces greatly increases the chance of the tower tumbling down.

When a journalist plagiarizes a piece of journalism’s credibility is lost, and the base of our industry’s Jenga tower weakens. A weak base means an unstable structure, which could come crashing down.