For one Halifax charity, COVID-19 amplifies existing challenges

Phoenix Youth says its services are needed more than ever, but costs are up

caption

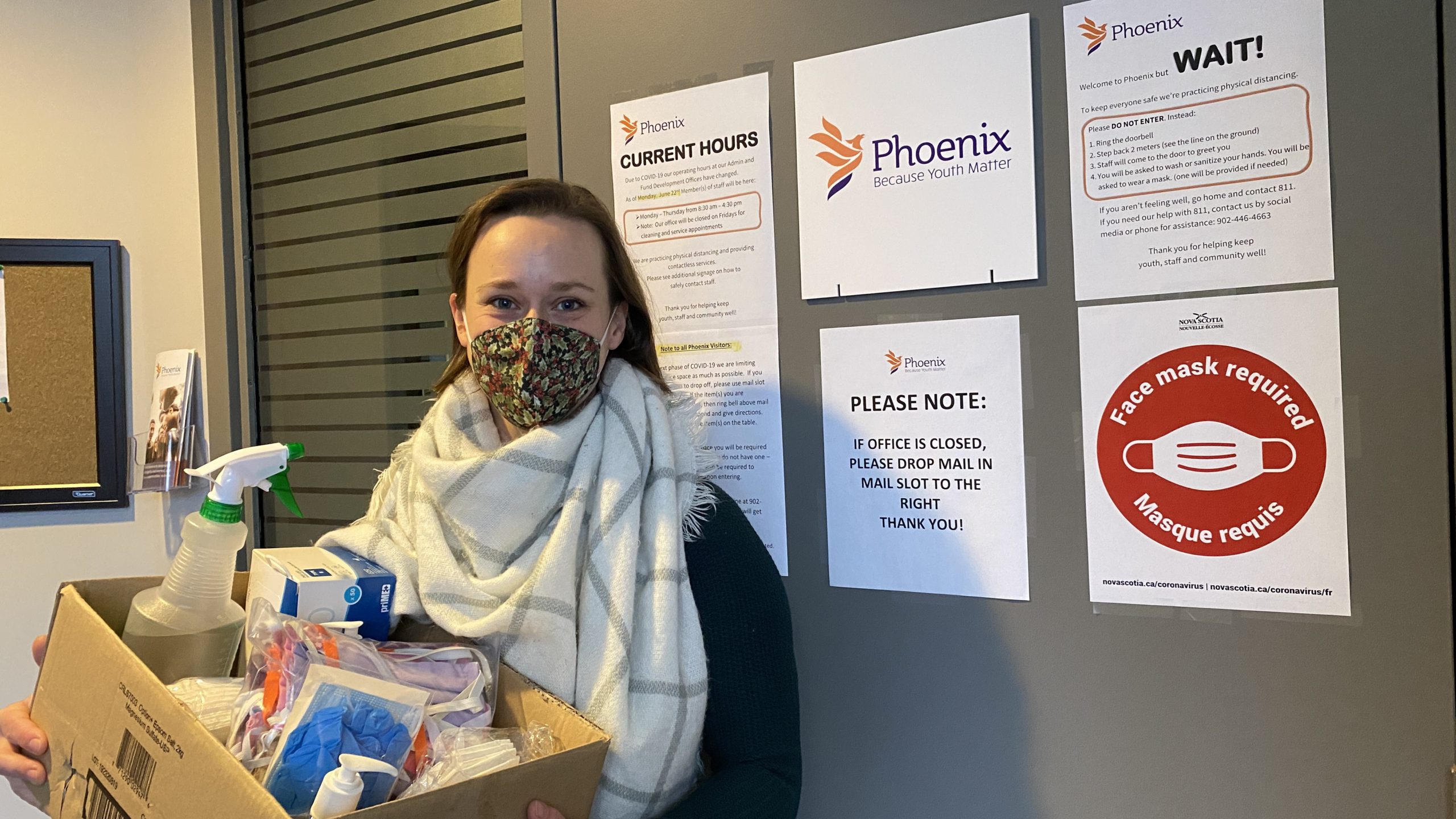

Melanie Sturk, director of organizational development for Phoenix Youth, poses outside her office with a box of cleaning supplies of the type being distributed to many of Phoenix's clients.Phoenix Youth, a Halifax charity that works with vulnerable young people, is grappling with a tighter budget and worsening social problems.

Melanie Sturk, Phoenix’s director of organizational development, said in an interview that COVID-19 has increased the severity of many challenges faced by at-risk youth.

“Everybody in our world is facing a high level of anxiety,” said Sturk. “But we’re doing everything we can to keep those impacts as limited as possible.”

Compounding the challenges Phoenix faces, pandemic safety measures and increased demand for Phoenix’s services have driven up operating expenses at the same time that the charity has been forced to restrict volunteerism and some types of donations.

Changing needs

Phoenix operates several youth shelters and a range of social support services throughout Halifax. Teens and young adults can visit one of the charity’s properties for help with financial management, parenting or finding housing, among other topics.

Sturk said that chief among the worsening problems for Halifax youth are housing insecurity, food insecurity, and issues around school and work.

“I would say there’s not a change in the type of problem, but a change in the complexity and the level of concern,” she said. “When we look at housing, for example, it’s partially related to the pandemic and it’s partially related to the extreme housing crisis that we’re seeing in our city.”

Mental health, although harder to quantify, likely also represents a growing challenge for Phoenix’s clients.

To protect its clients and staff, Phoenix has switched to an appointment-only model for all of its services except its shelters. And where possible, Sturk’s team now meets with youth remotely.

For example, Phoenix usually holds a seasonal luncheon for about 1,000 youth and donors. This year, the gathering was replaced with the Holiday Luncheon To Go, which offered supporters turkey dinner takeout. Donors also bought more than 250 meals for Phoenix clients, who had the food delivered to their doors.

“We’ve really just adapted the ways that we do things,” said Sturk. “Instead of just throwing in the towel, we’ve adjusted what we do … so that people aren’t going without.”

Budget crunch

For Phoenix, the financial cost of the new paradigm has been steep.

To reduce the risk of spreading the coronavirus, the work that would normally be done by volunteers is now completed by Phoenix’s roughly 100 paid employees, upping staffing costs.

Other forms of in-kind donations have also had to be nixed for safety reasons. The only non-monetary donations Phoenix now accepts are personal hygiene items, cold weather clothing, masks and cleaning supplies, gift certificates and bus tickets, baby supplies and stationery and art supplies.

Under normal conditions, in-kind donations account for about $1 million of the roughly $2 million in donations Phoenix receives annually. The policy changes have caused much of that economic value to evaporate, Sturk said.

So far, Phoenix has been paying its bills with the help of several grants, including the federal government’s Emergency Community Support Fund and non-profit Second Harvest.

But Sturk warns that the situation is potentially unsustainable.

“Could we handle this on an ongoing basis? No,” she said. “We’re taking advantage of every (grant) that can apply to us to help our clients, but we don’t expect those opportunities to last forever.”

Countrywide issues

Greg Thomson, research director for Charity Intelligence, says Phoenix is far from the only Canadian non-profit facing pandemic-related financial problems.

His organization matches donors with capital-efficient charities, and as part of the process, creates dossiers on non-profits across the country.

He said in an interview that financial reporting schedules mean it could still be as much as a year before exact numbers about the impact of COVID-19 on Canadian charities become available. But his team’s recent work suggests that many non-profits are grappling with the same loss of in-kind donations that Phoenix has suffered.

“Where donated goods are drying up … they either have to cut back on those programs or reallocate funds to be able to purchase those goods that they were receiving,” said Thompson.

Donors, meanwhile, may be growing more frugal. A September survey from the Angus Reid Institute found that, among Canadians who have given to charity at least once since 2018, more than a third have been donating less money during the pandemic.

Coupled with increased staffing costs as other charities mirror Phoenix’s decision to cut in-person volunteerism to prevent coronavirus transmission, Thompson says many non-profits could soon see their ability to continue operating thrown into question.

“Most charities have three months, maybe six months of cost coverage,” said Thompson. “So if an executive director is sitting there looking at a potential drop of 30 to 50 per cent of revenues … they’re going to have to make some tough choices.”

How to donate

Sturk said that the best way for perspective supporters to help Phoenix Youth during the pandemic is by donating money via the organization’s online portal.