Founder of University of King’s College was a slave owner, say researchers

Scholarly inquiry shows many university founders had deep ties to slavery

caption

University of King's College launched a scholarly inquiry into their historical connections with slavery in Feb. 2018. The results of that inquiry were presented during an information session Monday afternoon.The scholarly inquiry into the University of King’s College’s connections with slavery has determined the university’s founder, Rev. Charles Inglis, owned at least two enslaved people while living in New York.

Researchers Karolyn Smardz Frost and David W. States co-authored a 105-page paper commissioned for the inquiry. They found out about Inglis’ ties to slavery because ads were placed in New York newspapers when the enslaved people fled their owners and ran away.

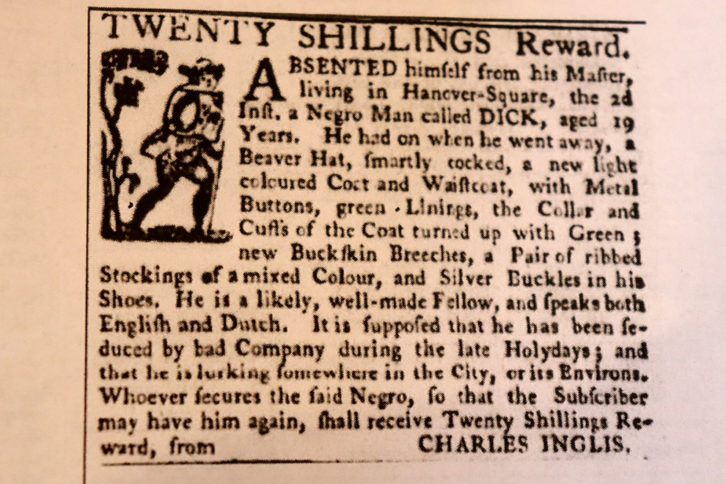

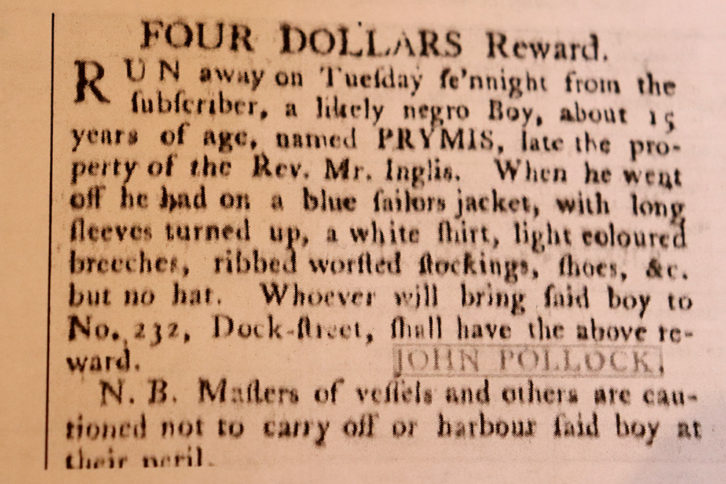

Inglis placed the first ad in 1773, offering 20 shillings for the return of a 19-year-old enslaved man named Dick. The second ad was placed in 1788 by another slave owner, John Pollock, who was looking for Prymis, a 15-year-old boy “late the property of the Rev. Mr. Inglis.”

caption

Rev. Charles Inglis, the founder of King’s College, placed this ad to track down an enslaved man who had fled from his ownership in 1773. Related stories

caption

An ad placed by slave owner John Pollock, who was looking for an enslaved person Inglis previously owned.It’s possible that Inglis enslaved more than two people. These ads are just the concrete evidence researchers have found to date.

But Inglis is far from the only figure from the university’s history with connections to slavery, as those attending an information session at the University of King’s College discovered on Monday.

“Our findings show that by far the larger proportion of individuals involved with King’s in the first generation either owned enslaved people before they immigrated to Canada, got them once they came here, or both,” Frost said during her talk.

“Those who did not often earned at least part of their income from handling slave-produced goods in one way or another through the West Indian trade.”

About 30 people sat in on Monday’s session in a university boardroom.

When the university launched its scholarly inquiry in February of 2018, four scholarly papers were commissioned in all, although only two were discussed on Monday. First, Shirley Tillotson spoke about her paper, How (and how much) King’s College benefited from slavery in the West Indies, 1789 to 1854. Frost and States also discussed their paper King’s College, Nova Scotia: Direct Connections with Slavery.

One of Tillotson’s key findings was that between 1803 and 1833, 35.7 per cent of King’s public funding came from taxes on slave-produced goods such as sugar.

“So the Canadian story is a tax story,” Tillotson said. “It’s a public revenue story. These colleges were funded, in large part, through taxes on slave-grown goods.”

King’s launched its scholarly inquiry into slavery on the heels of many other universities, including Dalhousie, Brown, Harvard, the University of Virginia, and the University of Glasgow.

With the findings of the inquiry in mind, the question many people who attended Monday’s session wanted answered was: What happens now?

Inquiry ‘not an endpoint’

Douglas Ruck, chair of the King’s board of governors, said people need to talk about the results and understand that “number one, slavery existed in Canada.”

“Secondly,” he added, “slavery existed in Nova Scotia. And thirdly, the legacy of slavery is still with us. The lady in Walmart, the police stops, the profiling. Those are all the legacies of slavery. It’s still with us.”

caption

William Lahey, Shirley Tillotson, David W. States, Karolyn Smardz Frost and Douglas Ruck all spoke at Monday’s information session about the history of slavery at King’s College.University of King’s College president William Lahey assured attendees, “Our scholarly inquiry is not an endpoint, and it’s certainly not an end in itself.”

He said the university wants to make King’s a place where African Nova Scotians can thrive.

“African Nova Scotians do not think of King’s as one of the universities that’s in Nova Scotia for them,” Lahey said. “And there’s a lot of reasons for that, and a lot of reasons that are much more current than our history of slavery in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and I want to change that.”

To that end, Lahey said the university is creating new scholarships, evolving education programs, hiring more diverse faculty members, and hiring a new standalone equity officer of a racialized background. He also pointed to the university’s involvement in the new Journalism Noire program, which aims to help young African Nova Scotians develop journalism skills.

Attendees also raised questions about 19th-century writer Thomas Chandler Haliburton’s views on slavery. At King’s, the name Haliburton is part of the scenery. Students can meet in the Haliburton Room, or join the Haliburton Society — the oldest English campus literary society in the British Commonwealth.

But some students have expressed unease with Haliburton’s writings on slavery, and are advocating that his name be removed from King’s institutions.

Lahey acknowledged the weight of students’ concerns, especially given the scholarly inquiry’s findings.

He added that Inglis’ history may also generate unease among students.

“We can’t get away from the fact that we were founded by Charles Inglis,” Lahey said.

“But how do we reflect the fullness of Charles Inglis’ history while recognizing that he’s the founder of the university?”

About the author

Andrea McGuire

Andrea McGuire is a journalism student from Newfoundland. Before coming to King's College, she completed a master's degree in folklore at Memorial...