Art

Halifax artist uses dome for 360-degree film on Halifax Explosion

'It’s not about making the thing, it’s about making the experience'

caption

caption

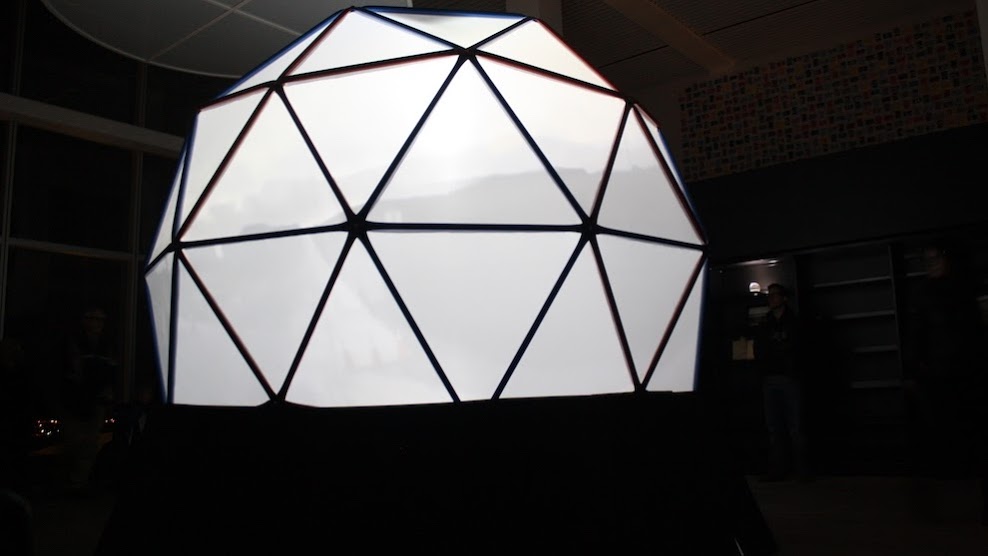

Barometer Falling’s glowing dome attracted visitors to the top floor of the Halifax Central Library during Nocturne.A 15-minute loop of 360-degree film walks through Halifax locations from Nova Scotia author Hugh MacLennan’s novel Barometer Rising, set during the week of the Halifax Explosion.

At last weekend’s Nocturne art festival, people lined the walls of the Halifax Central Library’s top floor to take in Halifax artist David Clark’s immersive film of the 1917 munitions blast, which devastated large areas of the city and killed almost 2,000 people.

The screen was a dome made of two jungle gyms from Costco and a custom screen made of projection fabric.

Clark’s installation, Barometer Falling, is the latest in his series called “Souvenirs from the Future.”

Clark teaches in the intermedia department at NSCAD University, where he mixes film, sculpture and web media. Lately, he has worked on incorporating new media like virtual reality and 360-degree video into his art.

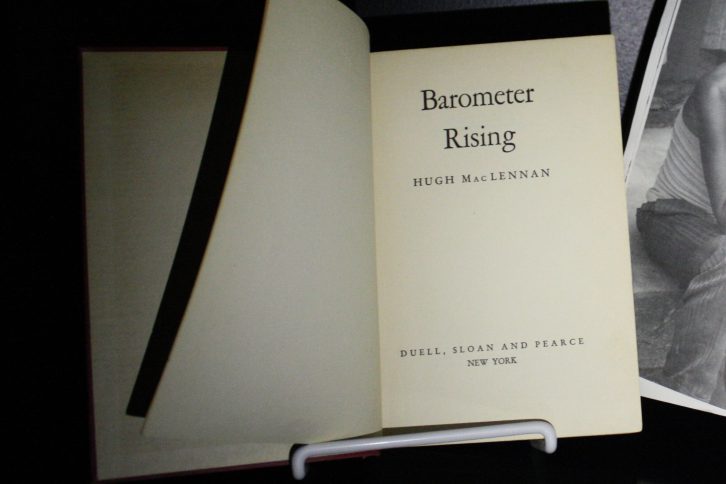

“It’s the first novel that uses Halifax as a recognizable city,” Clark says of the book, first published in 1941. “So as you’re reading it, you’re like, ‘there’s Barrington Street, there’s the Citadel,’ and you can map it.”

caption

The novel Barometer Rising was on display during Nocturne as part of Clark’s installation.A booming voice recites passages from the novel as disjointed and sometimes jarring footage of Halifax landmarks appear as they are today. Clark’s film seeks to contrast the present-day locations with the novel’s descriptions of 1917.

To make the film, Clark visited the locations with a 360-degree array made up of six GoPro cameras. After he shoots, he goes through “the elaborate process of stitching them together.”

His installation has aspects of both sculpture and bits of narrative. You can see a film anywhere, but Clark makes his films site-specific.

“I’ve been interested in is this new form of video that has this sense of place,” says Clark.

One scene in Barometer Falling was shot on the 5th floor of the Halifax Central Library, where the installation was held.

caption

A volunteer helps Clark set up his dome last FriAnother inspiration for the installation has been Clark’s research over the last three years into the films of Expo 67, the World Fair held in Montreal. He has worked with a team of mostly film historians.

“As an artist, I was invited into the project to kind of reflect on where we are now with this new technology,” says Clark.

More than 250 films were made to show at Expo 67. Notable films included one with a panoramic screen and another where the theatre rotated as the audience looked at a series of eleven screens.

After Expo 67, artists and filmmakers discussed how to get these new film technologies into wider use. In the following years, several of them went on to invent IMAX.

caption

Clark on the night of Nocturne.To Clark, Nocturne is an opportunity to see how people experience his art.

“It tell my film students that a film is never done until you see an audience seeing it because it’s not about making the thing, it’s about making the experience.”

He went into Nocturne not knowing how people would move around his piece, or how they’d react to the editing.

“You learn a lot about what the piece is going to be through watching people actually use it.”