climate change

Harbour rising

caption

A panoramic view towards the mouth of the Halifax Harbour, spanning the Dartmouth waterfront to the Halifax waterfront, from the centre of the A. Murray MacKay Bridge.Climate change will cause the waters in Halifax Harbour to rise by a metre or more, threatening more than a billion dollars of harbourfront real estate

Editor's Note

Lama Farhat, a Student Associate of the Dalhousie Libraries GIS Centre, worked with Dini on data analysis and visualization for this story. Farhat graduated from Dalhousie University in spring 2019 with a BSc in environmental science. James Boxall of the GIS Centre provided additonal supervision of Dini's project.

On the night of Jan. 4, 2018 as 30 km/h winds swept the surface of the Halifax Harbour, Jamie Rouse and his son-in-law were standing on the Fisherman’s Cove boardwalk just outside of Rouse’s seafood restaurant, Boondocks, warily watching the rising waters.

“We looked at the security cameras and I saw that the waters were getting up and close, so we came down to see it,” recalled Rouse.

Earl Gosse, a veteran board member of the Fisherman’s Cove Development Association, would recall more than a year later that it had been a spring tide on the night of that January winter storm. At precisely the time the two Nova Scotia restaurateurs had been standing on the boardwalk, the water was almost two metres high.

The planks beneath their feet started to move. Related stories

“We got off of that pretty quickly and … just basically came inside and watched it rip apart,” said Rouse. “It wasn’t until the morning that we saw the extent of the damage.”

caption

A portion of the Fisherman’s Cove boardwalk extending along McCormacks Beach Provincial Park is blanketed with a cascade of rocks that were sent flying by the storm.What was left of Fisherman’s Cove’s picturesque boardwalk, the pride of the restored 19th-century fishing village that rests on an infilled peninsula at the mouth of Halifax Harbour, was torn in two. One half was “embedded beneath our deck,” recalled Rouse, and the other half, “ripped up and shoved into the inner side of the parking lot,” said Gosse, who had been among the stunned spectators the following morning.

“It got shoved all the way over almost to the road, and that was lifting up concrete,” said Gosse. “Big concrete blocks, you know, a base — and they were down in the ground, so it pulled them up.”

While Gosse could hardly believe what he was seeing, Rouse expected nothing less from the sea.

“There’s not many things that can stand Mother Nature, you know,” he said. “It’s amazing that the water was only probably about two or three feet deep, at that, and to be able to lift up the concrete and move it.”

In fact, climate scientists project that Halifax Harbour’s surface could swell more than a metre higher over the next 80 years. Much more than the Fisherman’s Cove boardwalk would be buckling beneath those higher waters.

Not only would 1.5 more metres of water return Fisherman’s Cove’s artificial peninsula to the sea, but when future storms ride in violently atop those higher waters, an analysis by the Signal and Dalhousie’s GIS Centre found that more than 1,700 buildings along the length of the Halifax Harbour coastline could be inundated. These extreme water levels could affect properties assessed for taxes today at an amount approaching $2 billion.

This map shows an overlay of the potentially affected land and the existing buildings there:

Despite Halifax Regional Municipality’s vulnerability to the rising sea, millions of dollars continue to flow into raising the Halifax skyline. A drive to develop may today be dominating the Halifax waterfront, but the climate science warns that it will one day have to reckon with the rising seas. The city’s early September encounter with post-tropical storm Dorian, underlined once more the city’s potential vulnerability in the face of rising waters and fierce storms.

Rising water

caption

Artist Richard Short’s 1759 engraving of a view of Halifax, looking out to “the Sea off Chebucto Head” from today’s Prince Street.For 13 millennia since the end of the last Ice Age, people have been drawn to the coast of K’jipuktuk, “the biggest harbour” in the language of Nova Scotia’s earliest Mi’kMaq inhabitants. In 1749, the first British settlers to sail in on its “fine ice-free waters” would anglicize its name to the Harbour of Chebucto, and shortly after it would be renamed Halifax Harbour.

For the next 100 years, the coastal city of Halifax entered its golden “age of sail,” drawing countless merchant ships, privateers’ vessels and fishing boats to its harbour waters. At its height even the small and peripheral community of Fisherman’s Cove, then known simply as “the Crick”, would in 1881 support 86 families through fishing.

However, when those fishermen kissed their wives goodbye and pushed their boats off from Governors Wharf 100 years ago, tide gauge data from 1920 reveals that the harbour waters that their oars dipped into were more than 30 centimetres lower than the waters of today.

According to the International Panel on Climate Change, rising seas are a trend that’s been observed around the world, but in Halifax Harbour it’s been happening even faster. According to Blair Greenan, a sea level rise scientist at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, the retreat of a massive ice sheet across Canada thousands of years ago is partly to blame.

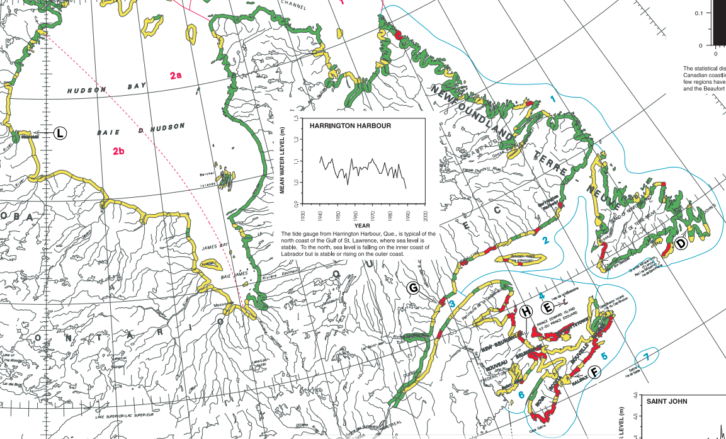

caption

While some two-thirds of Canada’s high risk shores on this 1997 map are traced in a cool green that indicates “low risk” to sea level rise, the mere three percent stained in a “high risk” red are largely concentrated in Maritime Canada.“Think of the Earth’s crust sort of like a little rubber ball that the ice is squeezing,” said Greenan as he curled his fingers around an imaginary stress ball. “Once you let the pressure off it sort of slowly rebounds back to its natural shape.”

Because the ice’s frozen grasp didn’t quite reach all the way over to Nova Scotia, he explained, the province did “a bit of a bulge up.” Once the ice began to retreat, Nova Scotia slowly started to sink back down into the ocean.

“When you compound that (sinking land) with global sea level rise, we’re seeing relative sea level rise here a little faster than the global average,” said Greenan.

In fact, according to the century-old data from the tide gauge beneath the A. Murray MacKay Bridge, the waters of Halifax Harbour have been rising at a rate of 3.2 millimetres a year; almost twice as fast as the global average. By the end of this century, the 2019 Canada’s Changing Climate report projects that the surface of Halifax Harbour could potentially rise a further 1.5 metres or more.

When the Signal and Dalhousie’s GIS Centre added on top of all this the extreme water levels that could be expected during a major storm event by 2100, we found that the harbour’s waters could plausibly surge up to downtown Halifax’s Hollis Street, up to 5.3 metres above the average sea level of today.

While it may be another 80 years before any sea water flows below the Old Triangle’s stained glass windows, the impacts of a higher Halifax Harbour are already being felt. They left their first major scars in the fall of 2003.

Hurricane Juan

In the early hours of the morning on Sept. 29, 2003, Hurricane Juan made landfall in Nova Scotia. It was a category two Hurricane, “it wasn’t a four or five and I don’t want to see one,” said one unnamed emergency official in a provincial record of a gathering in Dartmouth shortly after. Even so, with winds that reached maximum speeds of 185 km/h and some harbour waves that towered up to nine metres high, the storm was of historic proportions.

caption

A sunken sailboat slants underwater, still tied to a Halifax wharf after being shipwrecked by Hurricane Juan.“Hurricane Juan was truly a large-scale flooding event for Historic Properties,” recalled Scott McCrea, CEO of the investment and construction firm, Armour Group, which manages that strip of historical waterfront buildings. While extreme storm waters have “repeatedly” flowed past their granite and ironstone facades, “none, however, really compare to Hurricane Juan.”

Water infiltrated the properties’ waterfront buildings, and “penetrated all the way up to Water Street,” recalled McCrea. His team tried, in vain, to pump out the sea water pouring into a recessed electrical vault, but “when the salt water hit the electrical it exploded.”

“For Historic Properties as well as much of the waterfront, it was just a shocking (and difficult) experience,” said McCrea, “I think, in part, because no one truly expected that weather in force.”

However, during the gathering in Dartmouth, emergency officials were already suggesting that a repeat of Juan was “possible, if not likely.”

Twelve storms

While another storm on the scale of Hurricane Juan hasn’t happened yet, from 1991 to 2010 Nova Scotia was hit with a total of 12 major storms, amounting to more than $100 million in provincial and federal disaster relief expenditures alone. Almost $40 million of that went into just the relief of Hurricane Juan.

In the winter of 2018, McCrea would witness the properties’ third greatest flooding event in his lifetime.

The #Canada150 sign is moving. #NSStorm pic.twitter.com/hqpahzrqGj

— Steve Silva (@SteveCSilva) January 5, 2018

Across the Harbour from the shifting concrete slabs of the Fisherman’s Cove boardwalk, then-Global News video journalist Steve Silva tweeted out the waves as they crashed into the Halifax waterfront and collected in a torrent of flood waters that flowed down the boardwalk towards the Historic Properties.

caption

A peek at the Queen’s Marque construction site in the summer of 2019.As the kitchen staff at the seafood restaurant Salty’s were stacking sandbags to keep the water out and the bartender at the Lower Deck was already mopping at water about “three or four inches deep,” Silva walked towards the nearby construction site of Armour Group’s latest waterfront development, the $200 million Queen’s Marque, and tweeted out the sea water gushing into its foundation.

Here’s an update on the #QueensMarque situation. #NSStorm pic.twitter.com/z8YnXF6SKn

— Steve Silva (@SteveCSilva) January 5, 2018

Less than two years earlier, in the spring of 2016, McCrea was presenting Armour Group’s waterfront plans for the stately Queen’s Marque development to the city’s Design Review Committee. Envisioned in partnership with Develop Nova Scotia, the provincial Crown corporation that manages its waterfront lands, the Queen’s Marque’s historical marine materials and sweeping “ship shapes” harken back to the once-great power of the Queen and her navy.

caption

An artistic rendering of the completed Queen’s Marque, which will serve as restaurant, parkade, public plaza, shopping space, office, and home to 130 residential units.“It was a pleasure to look at the renderings,” said one committee member, architect Anna Sampson. “The site is remarkable,” said another similarly qualified expert, John Crace. Beyond a passing reference to the project’s “proximity to the water”, meeting minutes reveal that any concern over its risk to sea level rise was not expressed.

In fact, by that December it had been edged even closer to the water when the committee approved a variance requested in Armour Group’s site plan application to scale back the minimum eight-metre setback from the high tide waterline to as little as “three metres in some cases.”

“It’s almost like the desire to be on the waterfront still outweighs the potential risks in the decision-making process,” said Alexandra Baird Allen of real estate consulting firm Turner Drake & Partners. “Those properties are more at risk, and that probably will continue for the foreseeable future.”

Costs of sea level rise

According to Nancy Anningson, the coastal adaptation coordinator for the Ecology Action Centre, there needs to be community “buy-in” to the risks of sea level rise “if change is going to happen.” In an email to the Signal she identified images such as those in Silva’s tweets as “impactful, as it visually identifies just what we are talking about along Halifax’s waterfront.”

“Coastal climate change can be frightening and overwhelming; information needs to be relatable,” she said. “Seventy per cent of Nova Scotia’s population lives in coastal communities. People need to know and understand what is happening.”

According to Vanessa Barrasa from the Insurance Bureau of Canada, flooding in the four Atlantic provinces cost more $10 million in insured damages in 2018, a tenfold increase from the year before. Based on numbers reported in a 2018 media release from her organization, flooding from that January alone made up the lion’s share of the year’s insured damages from flooding.

“While the insured damage from these floods is significant,” said Craig Stewart, the bureau’s vice-president of federal affairs, in the media release about last winter’s storm, “the total economic cost to homeowners and the government is not yet known.”

caption

The Jan. 4, 2018 storm surges flung the boardwalk as far as the parking lot’s edge to the right. It was repaired and replaced a few months later but the wavering in its once-smooth lines reveal its scars.Down at the mouth of the Halifax Harbour, meeting minutes from Fisherman’s Cove’s board meetings on Jan. 10 and May 9 of 2018 reveal that just to repair the boardwalk would have cost nearly $10,000.

“In the end we didn’t have the money,” said Gosse, “so we got a bunch of volunteers and a couple of forklifts and we shoved it back in place and rebuilt it for free.”

Even so, by that February, Fisherman’s Cove’s books were already more than $6,000 in deficit due, in part, to “significant maintenance costs” following the storm. While it was certainly one of the community’s more traumatic events, Gloria McCluskey knows that it wasn’t the first and it won’t be the last.

“I remember coming down here one night and it was really stormy over there on the boardwalk, watching the breakers coming in,” recalled the prominent, but now retired, Dartmouth politician. She also recently left her post as a Fisherman’s Cove board member. “It was really the way it comes in around there. You’d think that with it being so narrow that it wouldn’t be as violent here, but it is.”

According to a 2012 vulnerability map from Halifax Regional Municipality, or HRM, Fisherman’s Cove and much of its neighbourhood have been “impacted by coastal flooding.” Many of its roadways have been “washed away or damaged by erosion and storm surge,” and at least three residential side streets have been “closed due to flooding.”

“The water comes right up there during storms,” said McCluskey about one of the 16 buildings identified along Shore Road as having previously flooded. The homeowner “had to install a big rock wall across the front to kind of keep the water out.” According to another record in a user-contributed sea level rise map from the Ecology Action Centre, a resident experiences flooding in their yard “after every storm and wave action.”

caption

Earl Gosse lifts a melted cable from the wench that reels in his boat docked at Fisherman’s Cove. The wooden enclosure caught fire on the night of Jan. 4, 2018, probably because the rising salt water “short out the two cables to the batteries,” he believes. “It was cold and wet enough that the fire didn’t get hold,” said Gosse.The analysis from the Signal and Dalhousie’s GIS Centre suggests that flooding like this may only be the beginning. By 2100, not merely 16 but as many as 244 of the buildings that today surround Fisherman’s Cove could potentially be inundated during an extreme storm. This could affect properties worth more than $76 million–as measured by tax assessors. Along the Halifax waterfront, potentially affected properties are today worth more than $900 million

When the entire harbourfront is considered, properties assessed today at approaching $2 billion could be affected in an extreme storm by 2100.

The exact impacts are impossible to know as so many variables are at play. The impacts are based on projections both of sea levels and of what an extreme storm could look like, assessed values may understate what properties are worth and there is no real way to know what properties will be worth in 80 years.

“That assessed value covers the value of the building (but) it’s really a best-case scenario,” explained realty expert Baird Allen over the phone about the accuracy of these values as a measure of total economic impact. She also used tax-assessed property values in her similar but more limited analysis for the Halifax Waterfront in 2017.

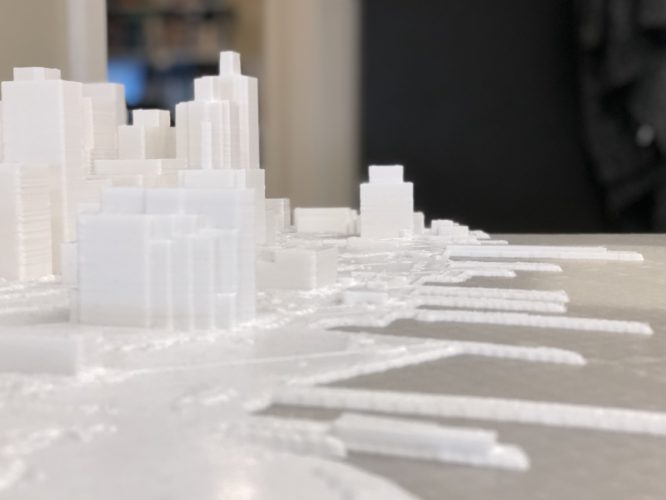

caption

A plastic model of the Halifax waterfront in Dalhousie’s GIS Centre’s headquarters“It doesn’t cover the value of the contents and it doesn’t cover the value of the business interests so those are going to be costs over and above any damage to the construction of the building,” she said.

According to a 2015 HRM case study from the Insurance Bureau of Canada, the impacts from sea level rise over the next 20 years alone could increase the costs to repair damaged infrastructure by as much as 85 per cent. However, the “direct and secondary” impacts from that infrastructure’s dysfunction on the province’s GDP would be much higher.

By as early as 2040, annual losses from coastal flooding could be increased “by a factor of seven,” from $400,000 to $3.1 million a year.

Unless steps are taken to “proactively manage” these risks now, warns a 2012 study commissioned by the city, coastal flooding in Canada from sea level rise could end up costing anywhere from $1 billion to $8 billion a year, “with higher than average cost impacts in Atlantic Canada.”

“We must take the necessary steps to limit these losses in the future,” stressed the Insurance Bureau’s Stewart after the organization reported that severe weather across Canada cost $1.9 billion in insured damages last year. “The cost of inaction is too high.”

Adapting

Less than a year after the destruction of Hurricane Juan, HRM’s policymakers listened. By the summer of 2004, the city started to make note of the “emerging concern” of climate change and rising sea levels, and requested “a modelling study to predict (its) impacts (by 2100) on the shoreline of Halifax Harbour.”

Sea levels…will seriously impact shoreline infrastructure…and will threaten low-lying buildings. When coupled with (extreme water levels), as was evidenced during Hurricane Juan, the potential long term risk to public safety and property is severe.2004 Planning Strategy, Halifax Regional Municipality

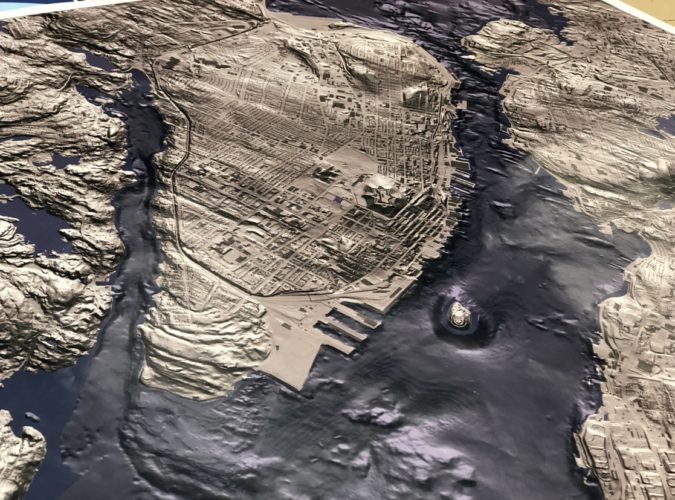

caption

Sea level rise modelling often involves Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) in order “to get a really good sense of what’s happening at the interface between coast and land,” said Shannon Miedema, a city official. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology is used to gather this data by bouncing lasers down from helicopters flown over the land, in order to produce a 3-D model such as this one of the Halifax peninsula pictured on this printed map in Dalhousie’s GIS Centre.“We cannot afford a wait-and-see approach when it comes to climate change,” said Roger Wells, then-supervisor of the city’s planning department shortly after the modelling study was finally completed in 2009. “That’s why we’re planning now for the next 100 years.”

Back in 2006, HRM adopted a new land-use bylaw that imposed a minimum elevation of 2.5 metres above the normal level of high tide for all new residential levels along the coast. According to Shannon Miedema, the city’s energy and environment program manager, after the modelling study “validated that number” in 2009, the elevation above high tide was converted in 2014 to a roughly equal but fixed elevation of 3.8 metres above the 1928 sea level for a more modern and consistent standard of measurement.

“Council chose (about) 2.5 metres above the ordinary high water mark in order to be really conservative and account for a pretty extreme scenario,” Miedema told the Signal. “That is where you can’t build residential floors of new developments: below that line, for the entire coastal area.”

The bylaw reflects the need to protect public safety when residents must take shelter in their homes, for example, during a hurricane…the intention is that the residential properties don’t get flooded in that scenario.Shannon Miedema, Energy & Environment, HRM

While HRM’s bylaw does attempt to ensure that no new homes will lie too close to the surface of the sea, the elevation of the buildings themselves are largely left up to the discretion of individual developers. By as early as 2008 on an unremarkable marine slip along the Dartmouth waterfront, Francis Fares would be one of the first to raise more than just his buildings’ residential floors.

caption

Developer Francis Fares stands over a model of the King’s Wharf developments, a work-in-progress. In addition to King’s Wharf’s four existing residential towers, Francis Fares’ plan and vision for the development includes waterfront townhouses, a marina, several public spaces, a commercial and grocery district, and even a beach.According to Fares, the man behind the King’s Wharf developments, from the very beginning he asked himself one simple question: “where is the elevation on the whole development?”

“It’s only a matter of time before the sea rises so we said: ‘Let’s go a little higher.’ It’s that simple,” he said.

Not stopping at 2.5 metres above high tide, Fares said that he raised King’s Wharf’s residential levels a further six metres above his lowest floors; a total height of almost eight metres above high tide. His lowest level, P2 for parking, is 1.8 metres above high tide.

“You don’t want your buildings stuck up in the air so they don’t interact with the water, but then again…you don’t want to have your buildings submerged in water,” said Fares. “You have to do a happy medium, and that’s what we decided to go with.”

Across the harbour on the Halifax side, McCrea was taking his own measures at Queen’s Marque.

caption

A view of the Queen’s Marque construction site from the Sea Bridge connecting the waterfront boardwalks it interrupts. With the project set to be completed later this year, construction is already well underway.“Because we’ve been making a massive — and it is a massive — investment on the water with Queen’s Marque,” said McCrea, “it would be foolish for us not to anticipate some level of sea rise over the next 100 years. We’ve done that in terms of the elevation of the project and in terms of the water proofing.”

caption

Passersby stop to size up the new building on the block as they stroll along the Halifax boardwalk.Its residential units begin at roughly six metres above today’s high tide level and its commercial ground floor is elevated roughly 1.6 metres above high tide; just a few inches lower than the King’s Wharf parking garage. Queen’s Marque’s parking is below the ground under the sea level, but as Peter Bigelow explained on his drive to work to the waterfront headquarters of Develop Nova Scotia, the parking’s garage opening “is sealed like a milk bottle.”

“You simply put a waterproof gate across and it becomes a barrier,” said the director of planning and development for the Crown corporation. “It’s kind of state of the art in terms of its ability to keep the water out.”

Not high enough

However, with seawater already pouring into its construction site as early as last January’s winter storm, realty expert Baird Allen noted that properties as close to the coast as the Queen’s Marque will have to be state of the art in order to keep dry.

“The scientific evidence that those properties are more at risk … is there and that probably will continue for the foreseeable future,” she said. “Adaptation and mitigation techniques are being incorporated but the all-stop to building on the waterfront hasn’t happened yet.”

caption

The most iconic buildings in the Halifax skyline are a part of the Purdy’s Wharf office complex. Its two office towers jut out past the edge of the Halifax waterfront and over the harbour, supported by pilings.Even though Baird Allen is critical of the limits of the response so far, she doesn’t believe that the answer really is as simple as banning all development along the coast.

“It’s an interesting balance of regulating people away from building close to the coastline … versus just saying, ‘well okay, fine, but it’s at your own risk,’” she said. “There is a lot of attraction to building on the waterfront. People still want to be close to the water.”

Sea level rise and climate change is an issue for the entire waterfront…as a waterfront province we are in a position to be leaders and innovators in creating spaces that can adapt to changing conditions through adaptive design.Lynette MacLeod, spokesperson for the Nova Scotia Department of Communities, Culture, and Heritage.

As Bigelow sees it, that won’t be changing anytime soon. He pointed out that human beings have been settling along the coast for thousands of years; that coastal living is in our very nature.

“The coastline offers us a richness, a fantastic place to live,” he said breathlessly into his cellphone as he hurried out of his car and along the Halifax boardwalk to catch his next meeting. “I don’t know if you’re from here but, you know, living along the shore is absolutely amazing.”

Indeed, for McCrea even the suggestion to ban all waterfront development is where he finds that the sea level rise discussion “becomes almost absurd.”

“Yes, it’s a concern, but past a certain point you would start to question any development on the peninsula, or any coastal development in Canada or the U.S.,” he said. “One would have to come up with very catastrophic predictions to believe that downtown development can’t and shouldn’t happen.”

However, according to the Insurance Bureau’s 2015 case study for HRM, the longer that the city continues to allow new building developments to take place on “flood prone land”, the more expensive it’s going to get. After examining HRM’s current land-use policies, the case study found that if business carries on as usual, buildings planned between now and as early as 2040 will account for almost two-thirds of all flood-related damages.

Even below the city’s minimum elevation for residential floors, at least 72 brand new developments have been approved for construction since the bylaw was first adopted back in 2006. This is all thanks to its narrow application to residential floors only. This map shows the locations of the permits:

According to the Insurance Bureau’s HRM case study, what the city decides to do now with the 130 sq. km or so of flood-prone land currently designated for future development will significantly influence the costs of future flood damage.

Planning for the future

With the surface of Halifax Harbour rising higher year by year, the city’s planners recognize that there is a lot at stake in getting HRM’s land-use policies right, now.

Climate change is getting higher up on people’s minds, we’re a coastal municipality, and we have, of course, a very important harbour.Ben Sivak, principal planner, HRM

“The (2.5) metre elevation was intended to keep residential spaces safe from the impacts of coastal flooding and storm surges during extreme weather events,” wrote Miedema, the city’s policy expert on the environment, in a follow-up email to the Signal about the limits of the coastal elevation bylaw. “With new information … we see an opportunity to enhance the bylaw, and consider extending it to commercial properties as well.”

However, before that can be done, Ben Sivak, the principal planner for HRM, said that there are two key “moving pieces”: the results from a new sea level rise modelling data and pending regulations from brand new province-wide coastal legislation.

On April 12, the provincial legislature passed the Coastal Protection Act, which will eventually roll out minimum setbacks and vertical allowances from the coast for all new developments across the province. According to Anningson from the Ecology Action Centre, these standards will finally “make things more consistent and effective.”

“It’s a terrific piece of legislation,” she said, noting that her environmental organization has been rallying for provincial coastal protection legislation for more than a decade. The act considers “coastal climate change realities and the need to…restrict coastal development in inappropriate places.”

“Although there are still baffling things that happen such as waterfront developments that are too close to the coast,” Anningson said, the act represents “a big change over the past year.”

Indeed, once the new regulations are in place, the coastal protections embedded in the act will be a big step for most Nova Scotian municipalities, many of which still don’t have any building setback requirements at all. However, it may do little more than play catch up with the policies already in place in HRM, already “a leader in the province when it comes to coastal climate change adaptation,” said Anningson.

Halifax Regional Municipality has done a lot of work…but there is still a lot of work to be done.Nancy Anningson, Coastal Adaptation Coordinator, EAC

HRM’s reputation for coastal regulation is something that Sivak, the city’s principal planner, pointed out to the Signal as well. However, he said that even if the Coastal Protection Act’s regulations impose “more stringent” building elevations than those of the city’s, expanding HRM’s coastal bylaw to apply beyond new residential levels wouldn’t happen without sacrifice.

“I don’t think anything’s off the table,” he said, but “I think the thing to keep in mind is that a big part of Atlantic planning is balancing multiple different interests.”

Balancing act

According to Lynette MacLeod, spokesperson for the Department of Communities, Culture, and Heritage, one of those interests is the preservation of our seafaring culture.

caption

Maritime artifacts are displayed in the store windows of the Robertson’s Hardware and Warehouse, an extension of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.“Museums play an important role in sharing our unique culture and heritage in Nova Scotia and Nova Scotia has a proud and longstanding history with the sea,” she told the Signal over email.

Nowhere is this more apparent than at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, which includes the registered municipal heritage property the Robertson’s Hardware and Warehouse, as well as a “vast collection of treasured artifacts,” said MacLeod.

When asked whether its waterfront location might put these municipal treasures at risk, she said that the museum has flood insurance, but that there are other, strategic benefits to being close to the water.

“The proximity of the Maritime Museum to the Halifax Harbour allows it to showcase our history in a unique and interactive way,” said MacLeod.

caption

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic rests right along the Halifax Boardwalk. Its pebble yard is littered with propellers, anchors, and boats in an interactive display that often attracts the swinging limbs of climbing children.According to Tourism Nova Scotia spokesperson Zandra Alexander, waterfront proximity is also essential in enriching the province’s tourism industry.

“Nova Scotia’s accessible coast offers many diverse opportunities for tourism operators and visitors to engage with Nova Scotia’s natural beauty,” she wrote in an email to the Signal. “We know that many people come to explore the sea coast, beaches and ocean, and experience the world’s highest tides.”

For that reason, over the next three years Tourism Nova Scotia’s Tourism Revitalization of Icons Program will invest $6 million to enhance five coastal destinations across the province: Peggy’s Cove, the Cabot Trail, the Bay of Fundy, the Lunenburg waterfront and the Halifax waterfront. Part of the latter’s $1.5 million allocation is already behind the funding for Develop Nova Scotia’s $100,000 strategy to bring visitors to the harbour islands, with Fisherman’s Cove as one potential access point.

caption

A view of Georges Island in the foreground from the Halifax waterfront. McNab’s Island, many times larger, stretches across the horizon in the distance.“It’s quite a spot; kind of mysterious,” said McCluskey, who is cautiously optimistic about the project for McNabs Island. Even though the historic island and park have been accessible through tours organized by the Friends of McNabs Island Society since 1991, society representative Cathy McCarthy said that Develop Nova Scotia’s involvement could increase tourism access from Eastern Passage with the restoration and development of coastal infrastructure, such as the dilapidated Range Pier.

Alexander said that Tourism Nova Scotia’s revitalization program considers the sustainability of all of its coastal projects and that sea level rise was specifically studied in the case of the harbour islands strategy. However, she said that “social/cultural sustainability is also considered, such as benefit to the quality of life in communities which tourism can enhance.”

caption

Boondock’s back deck sits right along Fisherman’s Cove boardwalk next to the harbour. Its waterfront proximity makes it vulnerable to destruction, as was the case during the Jan. 4 2018 storm, but its seaside views also makes it desirable for tourists.Indeed, while Rouse’s seafood restaurant Boondock’s may already be at risk to rising waters, he said that its waterfront location along the Fisherman’s Cove boardwalk is also the secret to its success.

“People want to come here because we’re right on the water,” Rouse said. “You could put the biggest flood barriers up and it’s just going to detract from people wanting to come here.”

In order to keep them coming and despite Fisherman’s Cove’s vulnerability to the rising water, this past April District 3 Councillor Bill Karsten advocated for a $566,000 contribution of municipal funds toward a $1.7 million dock project for the historic fishing village, in order to “bring more economic opportunities for tourism to Eastern Passage.” According to McCluskey, the former Fisherman’s Cove board member, the investment is needed and welcome.

It’s the experience of being on the water and near all that, ‘cause if you took this (Fisherman’s Cove) and put it up here (away from the water), nobody’s going to be interested. It’s down here where people want to be.Earl Gosse, FCDA board member

“It’s always money here, right,” she said. “The only money we get is from the rents, the shops, and that’s seasonal.”

According to a 1998 thesis by Andrew MacDonald, Fisherman’s Cove attracted 100,000 tourists in the summer season of 1997, including up to 14,000 spectators alone to its Sharkarma Fishing Derby weekend. Fisherman’s Cove’s Business Manager Michelle Carbotte speculated that, if anything, attendance has since gone up. That said, she acknowledged to the Signal that only 2,500 people showed up this year for its 2019 Canada Day celebration, one of the cove’s two biggest summer events.

Indeed, across the harbour along the Halifax waterfront, boardwalks have meant big business for the city. According to Develop Nova Scotia’s 2018 Annual report, an estimated 4.6 million non-residents have spent a combined $1.6 billion in “Halifax waterfront-attributable spending” over the last seven years. In 2017, a record 2.9 million pairs of resident and visitor feet alike stomped along its wooden planks to play by the Halifax seashore.

“The coast is where people want to be; there’s lots of businesses that rely on being close to the water,” said city planner Sivak. “It’s an effort to try and balance those interests of waterfront developments and so-on, with our responsibility to take into account public health and safety.”

In order to reconcile this tension, Sivak said that he relies on a “common distinction between someone’s place of living and someone’s place of business.”

caption

Four of King’s Wharf’s main residential towers – from left to right the Aqua Vista, the Killick, the Keelson, and the Anchorage – face out from Dartmouth towards the Halifax waterfront. While these are raised 1.8 metres above the high tide harbour waters below, Francis Fares said that the fifth and tallest building, Brightwork, has the potential to be raised even higher once its construction begins.If “people can’t get into their home that’s a problem, that’s a big challenge,” he said. “If someone’s business gets damaged from storm waters, yes that’s a hardship, but at least they have a place to go home to.”

In designing King’s Wharf, Fares embraced this distinction when he chose to raise his residential developments at least 1.8 metres above high tide. He said that even if his lowest P2 level may one day flood, “it’s not a big deal; it’s not a living space.”

“Whether or not this is the best balance going forward is an ongoing conversation in Halifax and across the world, for that matter,” said Sivak. “It’s something that I expect we will be revisiting again and again in the coming years.”

Business as usual

While Sivak is happy to keep the conversation going, for District 12 Councillor Richard Zurawski the prospect of any further discussion brings him to “beyond frustration.”

“I’ve been talking and playing nice for 40 years and it’s gotten us squat,” he said. “We debate and we talk and we prattle on and we do virtually nothing.”

It’s the, ‘oh we still have time, we can still do this, things are not that bad, we’ll talk about it some more,’ which is the issue.Councillor Richard Zurawski, District 12

A self-described environmentalist who keeps wearing his clothes “until they fall apart,” Zurawski made his 2016 debut in municipal politics as “an active promoter of evidence based, conscientious decision making,” according to his city bio.

“I think council and all levels of government have not done a very good job at reacting to the climate change reality,” he said. “So far, two and a half years into my mandate, I’m not optimistic that we’re, at all, dealing with things the way we’re supposed to be dealing with things.”

The 2012 study that was commissioned by the city found that Nova Scotia’s coastal setback regulations “jeopardize waterfront development.” As a result, it recommended that the city prohibit new residential developments within a 20-to-30-metre-buffer from the coastline. However, in the 2014 review of the Regional Plan, city staff dismissed the study’s recommendation as “an impractical and unnecessary requirement” because it would “negatively impact planned or proposed future residential developments along the…waterfronts.”

“I just don’t understand why we’re not at a climate emergency stage of our actions,” said Zurawski. “We’ll do what is easy, and what’s politically expedient but we’re not willing…to do the heavy lifting.”

caption

The entrance to Halifax City Hall, home to HRM’s municipal government.On Jan. 29, Zurawski submitted a motion to council that includes a demand for the recognition that “the breakdown of the stable climate and sea levels under which human civilization developed constitutes an emergency for HRM.”

“There is a climate emergency declared by other Canadian Cities and it is time for Halifax to take a serious look at this issue,” the motion says.

While council did agree to officially recognize climate change and rising sea levels as an emergency for the city, HRM has since approved yet another multi-million-dollar building right at the harbourfront’s edge.

Just a few days after the Coastal Protection Act was signed into law, the province announced the relocation of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia from its already-downtown location on Hollis Street to a new $130 building at the bottom of Salter Street.

“I can’t think of a better place than finding a location on our waterfront,” said Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil to the Globe and Mail on the Art Gallery’s new home.

“We are not willing to change and it disturbs me greatly,” said Zurawski. “I’m coming to the opinion that if we don’t do something really drastic soon, I don’t give us much hope.”

A little more fill

Six years ago on a cloudy summer day during his second term with the Fisherman’s Cove Development Association, Gosse was standing in the centre of a modest crowd of reporters as they covered the construction of a brand new boardwalk for Fisherman’s Cove.

caption

FCDA board members Earl Gosse and Gloria McCluskey stand in front of Fisherman’s Cove’s colourful line of shops on a cloudy, windy day.This past April as he sat by the big glass windows in Fisherman’s Cove’s Heritage Centre next to then-fellow board member McCluskey, Gosse recalled how the original boardwalk had been “wiped out” from a storm, now more than a decade ago.

“It was just left there all scattered all over the place and broken up for three or four years, totally destroyed, just nobody doing anything about it,” he said.

caption

The boardwalk at Fisherman’s Cove is still anchored by concrete blocks today, but after the 2018 January winter storm tore them out of the ground, they now rest on top of the gravel.Then on June 25, 2013, funding from a $22,500 provincial grant finally did, and reconstructing the boardwalk became Fisherman’s Cove’s “first priority”. Gosse said that contractors anchored heavy concrete bases deep into the ground and bolted brand new wooden planks down on top of those.

“Now it’s built well enough that it can withstand the kind of storms, high tides and pounding surf that we get out here,” Gosse told the gaggle of reporters back in 2013. “It’s built to last.”

Less than five years later on that January winter night, Fisherman’s Cove’s boardwalk would once again be destroyed by the sea.

“Years after that I said, ‘so this is the way coastal boardwalks should be built,’ right, and I stood by the job thinking it was awesome,” said Gosse. “Then last year it just got wiped right out.”

Even so, as Gosse now approaches his late 70s he said that sea level rise “is the least of my worries.”

“The world will be all different in 80 years’ time…I won’t be alive, Gloria might be,” he joked, in a nod to the force that is McCluskey.

McCluskey, now in her late 80s, smiled but looked out of the Heritage Centre’s windows towards the Halifax Harbour before saying what she thought about the rising waters.

“We won’t know about it, but you will.”