How can journalists regain society’s trust?

caption

Seven renowned journalists offer solutions

It was the Saturday afternoon following June’s referendum, when British citizens voted to leave the European Union. Lamenting the vote – stretching hundreds of meters while blocking traffic lanes – over three thousand protestors marched through central London.

Watching the rally live from the CBC News World Network studio in Toronto, journalist Janet Stewart asked a protestor about the low voter turnout for young people.

Her answer baffled Stewart, “We didn’t know we might lose.”

Stewart, host of CBC Winnipeg News at 6 p.m. and Radio noon on CBC Radio One says she’s scared for the state of journalism. She’s fearful people are only putting faith in the news they want to hear.

Journalists everywhere are realizing we have a serious problem: our relationship with society is hanging by a continuously thinning string.

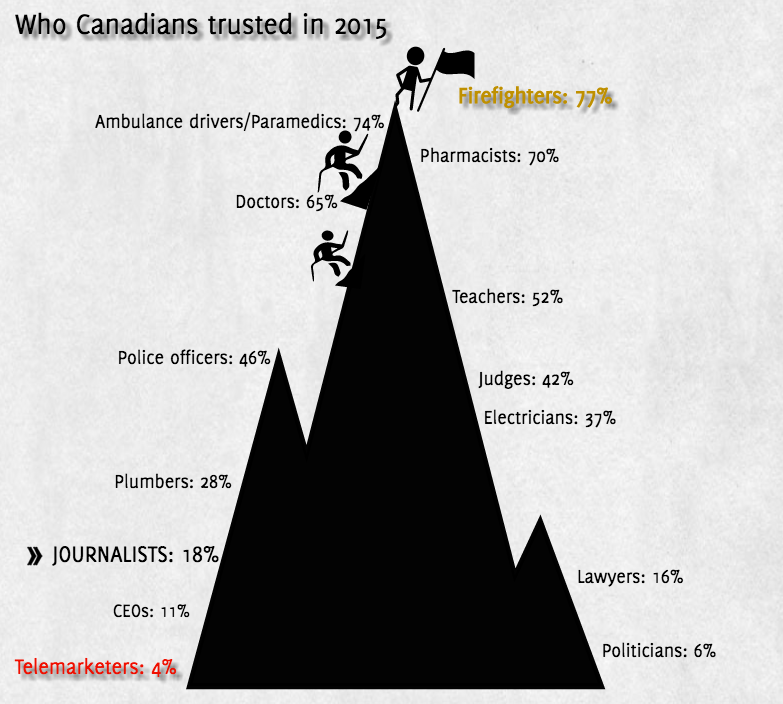

The number of people who trust journalists is shrinking. According to Ipsos Reid’s 2015 survey, journalists earn the trust of 18 per cent of Canadians, just two points higher than lawyers and auto mechanics.

Walter Cronkite, a CBS broadcast journalist in the ’60s, was considered the “most trusted man in America.” He brought assassinations, war and the first steps on the moon into the living rooms of millions. Now, 50 years later, Gallup’s 2015 survey reports less than half of Americans trust the media.

Here to suggest how to regain society’s trust are seven well-known journalists, including Nicholas Lemann of the New Yorker, John Branch of the New York Times and Ian Hanomansing of CBC’s the National. They propose journalists revisit core ethical beliefs, clearly define who is now a journalist, and redouble the fight for truth in these turbulent times.

Reputation bruises

Every profession has its horror stories – told in the hope they never reoccur. Many journalists have left marks on our reputation. In particular, we can thank Jayson Blair for a deep scar.

On May 11, 2003 the New York Times printed a 7,239-word front-page article with the headline Correcting the Record: Times Reporter Who Resigned Leaves Long Trail of Deception. Blair, 27, got caught in a web of his lies. In an effort to correct the record, the Times discovered he plagiarized and/or fabricated almost half of the articles he wrote during the last seven months of his four years with the paper.

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer John Branch (although he wasn’t writing for the paper at the time) says Blair’s actions “rocked the Times to its core,” and caused a “major hit” to its reputation. More than ten years later, Branch says the scandal is still mentioned in the newsroom.

Blair’s scandal isn’t an isolated affair – journalists have more stories that will leave you sleeping with the lights on. The scariest part: they’re true.

The fake news epidemic is spreading like a virus. Lies, propaganda and advertisements are attacking the truth. This infection is spreading the Internet without an end in sight.

Buzzfeed says between August and November on Facebook 8.7 million people engaged with false U.S. election stories, while 7.3 engaged with mainstream news U.S. election stories.

Branch says journalism is more important than ever. “The world’s becoming more complicated and we need more people to help explain it.”

Why society doesn’t trust journalists

Society’s loss of trust in journalists stems from a muddling of the definition of journalism. Growing up in an era before cable television and the Internet, Nicholas Lemann recalls when the word journalists referred to one main media source: newspapers. Now, people are forced to sort through all kinds of people claiming to be journalists.

You don’t need particular clothes, a diploma or business card to be considered a journalist, but Lemann says you do need a commitment to getting “as close to the truth as possible.” He considers the most important role of the journalist to be “grappling with the complexity of the world.”

Lemann, a professor of journalism and Dean Emeritus of the Faculty of Journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and a regular writer for the New Yorker, puts it simply. “We’re outnumbered.”

The U.S. Department of Labor reported in 2014 that public relations professionals outumbered journalists by a ratio of 4.6 to 1. With opinion-driven “citizen journalists”, both cynical and well-meaning satirists, and some Blair-like writers at work, society now has difficulty distinguishing who is a real journalist.

caption

Source: Ipsos Reid’s 2015 survey of Canada’s most and least trusted professions. Created with easel.ly.People question whether real journalists – the people committed to getting “as close to the truth as possible” – are on their side. Somehow, journalists have become the other, the enemy.

Society is being swamped by massive amounts of information, yet there are fewer local news outlets. As a result, Globe and Mail columnist Elizabeth Renzetti says people are “seeing less of their reality in what’s reported.”

Holding powerful people accountable is a cardinal pillar of journalism, and one way in which journalists serve society. But it has triggered a negative attitude towards journalists. “The media,” she says, “is a victim of their own success.”

Although she feels trusted by the public overall, Renzetti recalls the first time she witnessed paranoia about the press. It was outside a London courtroom in January 2011, when Julian Assange was on trial for alleged sexual offenses.

As Renzetti approached a group of Assange supporters they put on grinning Anonymous-style masks. When she asked why they were hiding, a woman said it was because Renzetti was a member of the mainstream media. This meant she “wouldn’t print the truth.”

Repairing the relationship

As trust for the journalist falls the landscape of journalism itself continues to shift. We face criticism, deadlines and an increasing pressure to put out fast news.

Cecil Rosner says we need to come up for air before jumping on a story. Overseeing about 40 stories a day, the managing editor of CBC Manitoba is tasked with many tough decisions. Before covering a story, he says, journalists need to weigh the public’s interest against possible harm. Whether you’re reporting on suicide, sexual assault or any other serious issue you have to, if possible, minimize harm.

Media ethicist Stephen J.A.Ward is the founding director of the Center for Journalism Ethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2015 be wrote the book Radical Media Ethics: A Global Approach. As the title suggests, Ward believes journalists need radical ethical reform. His solution includes opening journalism’s doors to the public.

Listen to Ward’s view:

To repair the journalism-society relationship, he says, we should bring citizens from diverse communities into the newsroom – better coverage of social issues would follow. Offer the public a seat at the table, he says, and it will kill the idea that “a bunch of old guys drinking Scotch in the back room” call the shots.

Ian Hanomansing agrees that journalists need to engage more with the public. His solution: transparency.

He hosts CBC’s News Network with Ian Hanomansing and reports for CBC’s the National in Vancouver. He says journalists need to do a better job of telling the public “the whole story.”

Too often, journalists are posing questions without answers – and vice versa. “Good coverage,” he says, includes addressing any conflict of interest, expressing where you got your information and giving context as to why you’re reporting on something.

For example, on the day Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie filed for divorce, people in Aleppo were under siege. Did the celebrity breakup affect Canadians? No, but CBC ran the story. Before going on air Hanomansing considered the public’s reaction. He decided to explain to viewers that, while a serious news network, sometimes CBC reports on “less important stories” people are talking about.

Ward, who promotes human rights in his ethical principles, says mending the division between journalist and citizen will require recognizing what connects us: our humanity.

During his time as a foreign reporter, before the first Gulf War, in the mountains of southern Turkey, a group of Kurdish refugees sought shelter from Saddam Hussein. Surrounded by people living in makeshift tents topped with blankets, Ward questioned whether or not to put down the pen to help in more immediate ways.

One of the refugees approached him, placing a note in his palm. He asked his translator for the message. It read, “Keep telling the world about this. You need to tell the world about this.”

This experience shaped Ward’s perspective of the relationship between journalism and society. Journalists need to rise to the level of reporting fairly and accurately not just on friends, neighbours and countrymen, but everyone.

“You have to be solidly committed to the common good.”