How social media revealed the importance of Indigenous issues during the federal election

caption

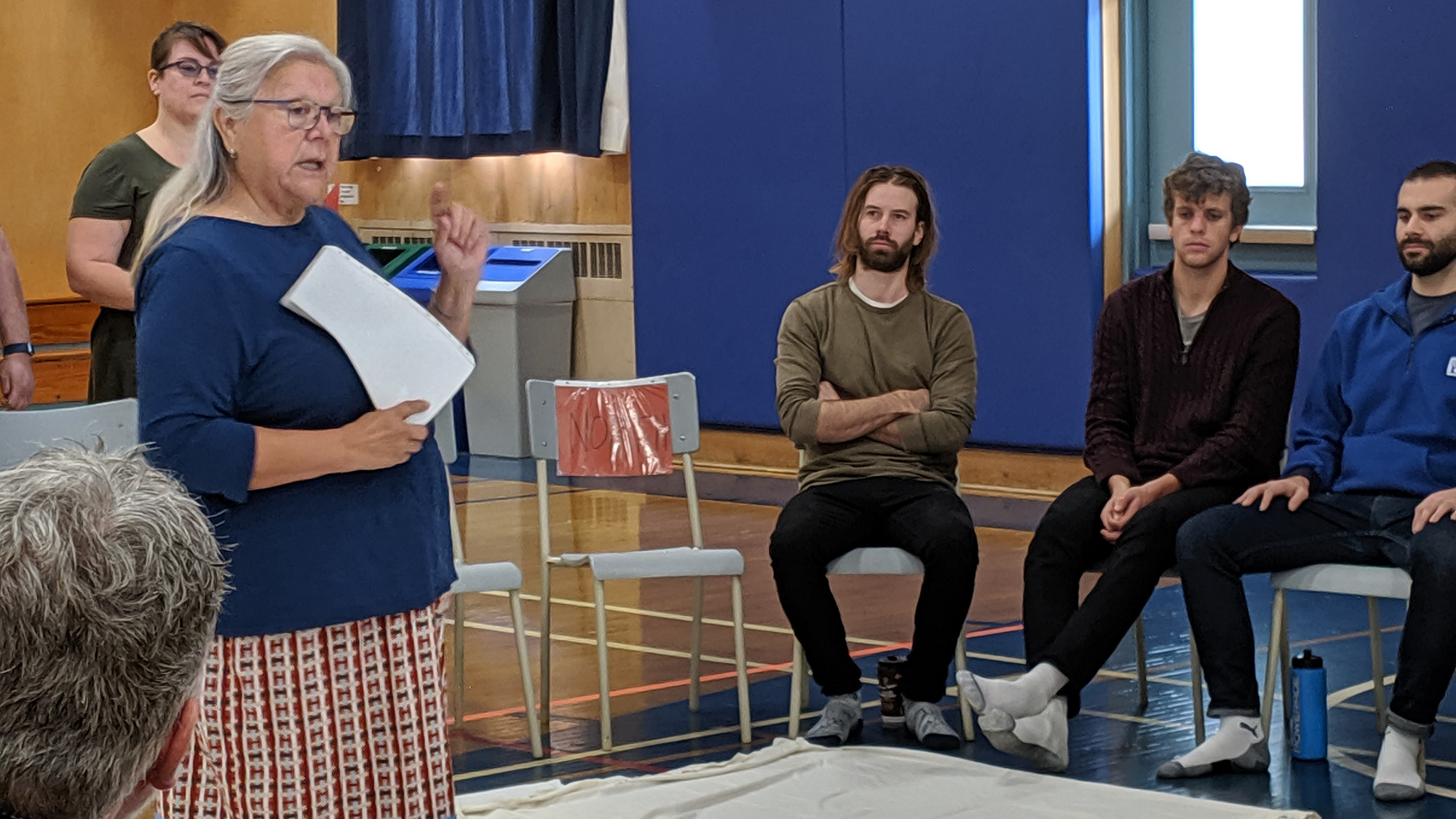

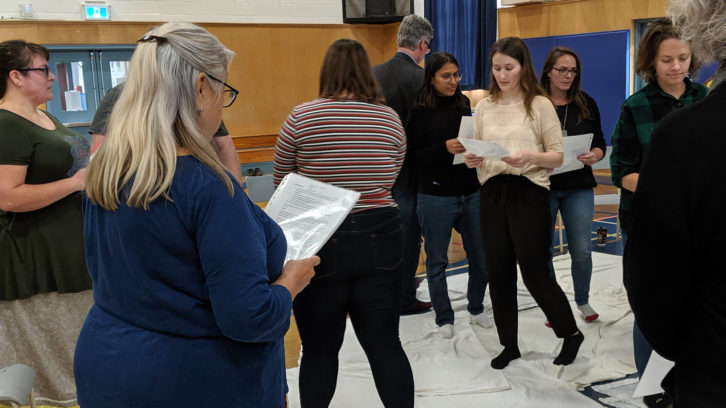

Geri Musqua-LeBlanc begins a blanket ceremony with a group of University of King's journalism students to teach them about Canadian-Indigenous history.From September to October 2019, Jean-François Savard was fixated on social media, but he wasn’t interested in the latest meme or pictures of cute animals. He was tracking politics.

Savard is the lead researcher on a project that examined the tweets of Canadian MPs during the recent federal election and how they addressed Indigenous issues.

“For us, it was mainly so that people can be aware how their candidates, and how the political party, talks about important issues like Indigenous issues,” Savard said.

He and his team looked at tweets from Bloc Quebecois, Conservative Party of Canada, Green Party, Liberal Party and New Democratic Party candidates from Sept. 11 to Oct. 21. Related stories

It's not 2015, but Liberals still win almost all seats in Nova Scotia

Savard said his team used a tool to track tweets and extracted key words and sentences about Indigenous issues. Then, they created the easy-to-read online visuals for voter interpretation.

“When Andrew Scheer gave five major policy speeches outlining his party’s priorities, he didn’t mention the words Indigenous or reconciliation once,” read a Sept. 12 tweet from Seamus O’Regan, Liberal incumbent for the St. John’s South-Mount Pearl riding.

Of the hundreds of tweets published about Indigenous issues during the first week of the campaign, Savard, who is also an associate professor at École nationale d’administration publique (ENAP), found O’Regan’s post was the most retweeted, at 130 times.

Savard’s team’s project, The Attention Paid to Indigenous Issues in Twitter by Candidates in Federal Elections, will be presented in 2020 as a part of a grant requirement. However, Savard said its main purpose is public accessibility.

Isabelle Caron, a professor in Dalhousie’s School of Public Administration, was part of Savard’s team and will analyze the data.

caption

Before starting her data analysis, Isabelle Caron said leaders weren’t raising “important questions about Indigenous communities.”She was surprised with the apparent lack of attention paid to missing and murdered Indigenous women, a topic that’s at the forefront of recent social activist and advocacy campaigns.

“From what I’ve seen, so far, (the topic) is really not an important issue during the campaign right now, and I’m surprised because I thought it would have been something more important,” Caron said during an interview in mid-October.

During the election campaign, Savard found the English words rights, communities, and reconciliation and the French words santé (health), enfants (children) and crise (crisis) were used most often.

Despite hundreds of tweets from politicians addressing Canadian-Indigenous topics, Geri Musqua-LeBlanc, co-ordinator of the Dalhousie Elders in Residence, said the candidates’ tweets don’t mean anything.

“I have no faith whatsoever that they will do anything about what they’re talking about,” Musqua-LeBlanc said during an interview in the middle of the campaign.

She said she’s not the only one who doesn’t trust their promises. Musqua-LeBlanc, who is part of the Keeseekoose First Nation in Saskatchewan and a residential school survivor, said a large demographic of Indigenous people don’t vote because they don’t trust officials.

This is changing though.

“In my generation, people just didn’t vote. They didn’t let government people onto reserves,” she said. “Now that the younger generation is out of the reserves, or off the reserves, and they’re out here and they’re taking advantage of the western education, we want them to vote.”

This idea of speaking about Indigenous issues goes along with what Musqua-LeBlanc does as an elder-in-residence. She offers spiritual and cultural support to students and conducts ceremonies, but education about Indigenous affairs is a major part of her role.

caption

Musqua-LeBlanc’s blanket ceremony surprised some journalism students with a history lesson they hadn’t been taught before.“My goal is to teach people how to work towards reconciliation,” said Musqua-LeBlanc.

Her blanket ceremony is meant to educate students about the Canadian-Indigenous past. Musqua-LeBlanc leads people through history on a carpet of blankets representing Turtle Island (or Canada).

On a campus scale she shows why political discussions of Indigenous issues, like numerous topics outlined in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action, are important.

Musqua-LeBlanc said politicians make promises to Indigenous communities to address pertinent issues like these. She said it’s meant to sway the population in their favour, referencing Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s 2015 campaign which put emphasis on Indigenous affairs.

One of the promises Musqua-LeBlanc feels Trudeau failed to complete in his first term was implementing the 94 calls to action demanded by the TRC.

“They’ll just mention it so that they’ll catch our ears, which is what happened when Trudeau got in. It was the Indigenous people who voted him in because he had all these big promises,” Musqua-LeBlanc said. “You have to start living up to what it is you promise, and what it is you say.”

She wants explicit deadlines for goals, so politicians are held accountable.

Now, the public can use Savard’s research to look at which parties are most vocal about Indigenous issues, down to specific details like the riding and gender of those tweeting.

When asked if the research would influence her vote, Musqua-LeBlanc said she would look at it, but couldn’t base her vote on promises alone. She wants action.

“It was only last week that I decided who I should vote for,” she said in mid-October. “There was also only one person, one party, that came to my door.

“I challenged a lot of what that person said, and this person was shocked that I was challenging her points of view. I said ‘Well, you have not mentioned anything that your party would do for Indigenous people,’ and it literally shocked her.”

The candidate, Emma Norton, left shortly after. To Musqua-LeBlanc’s surprise, she returned a half-hour later with tobacco and thanked the elder for their discussion. Musqua-LeBlanc knew then who she was going to vote for.

Norton lost the seat, Dartmouth-Cole Harbour, to Liberal candidate Darren Fisher.

Savard’s data found NDP candidates tweeted most often about Indigenous issues, more than 500 times over the campaign.

Although, as a collective, Canadian candidates tweeted over 1,000 times about Indigenous issues, that doesn’t help Musqua-LeBlanc.

She wants accountability, but research tools like the Twitter data may not help.

Caron doesn’t see the tool being effective at holding politicians accountable or determining if it had any effect on the election.

The importance here, Caron said, is not getting the “whole picture.”

“We barely talk about specific candidates. We always have one picture of one person but it’s not necessarily representing the whole, all the candidates,” she said.

Despite the research’s purpose to educate the public, Caron said they won’t be able to measure the effect it has on voting.

Currently only quantitative information is available to analyze, but even those results are surprising to Savard. After working on Indigenous policy for 25 years, he said he was expecting more tweets about Indigenous issues. He was surprised about a lack of contributions from francophone candidates.

Savard said he and his team hope to do similar projects during future elections, but with different data and data from more parties.

Caron thought it would be interesting, given the resources, to continue the project through the next four years to see if elected politicians continue to tweet about Indigenous issues.

While Caron’s and Savard’s work ends with the election of Trudeau’s minority Liberal government, Musqua-LeBlanc’s work of educating will continue. Instead of listening to politicians make blanket statements about Indigenous issues, she will use blanket ceremonies and other means of education to work toward reconciliation.

About the author

Dayne Patterson

Dayne Patterson is a recent graduate student at the University of King's College. He's reported from all over Canada, including B.C., Alberta,...