Explainer

How to exercise your rights as a tenant in Nova Scotia

Legal aid lawyer outlines landlord-tenant legislation in free workshop

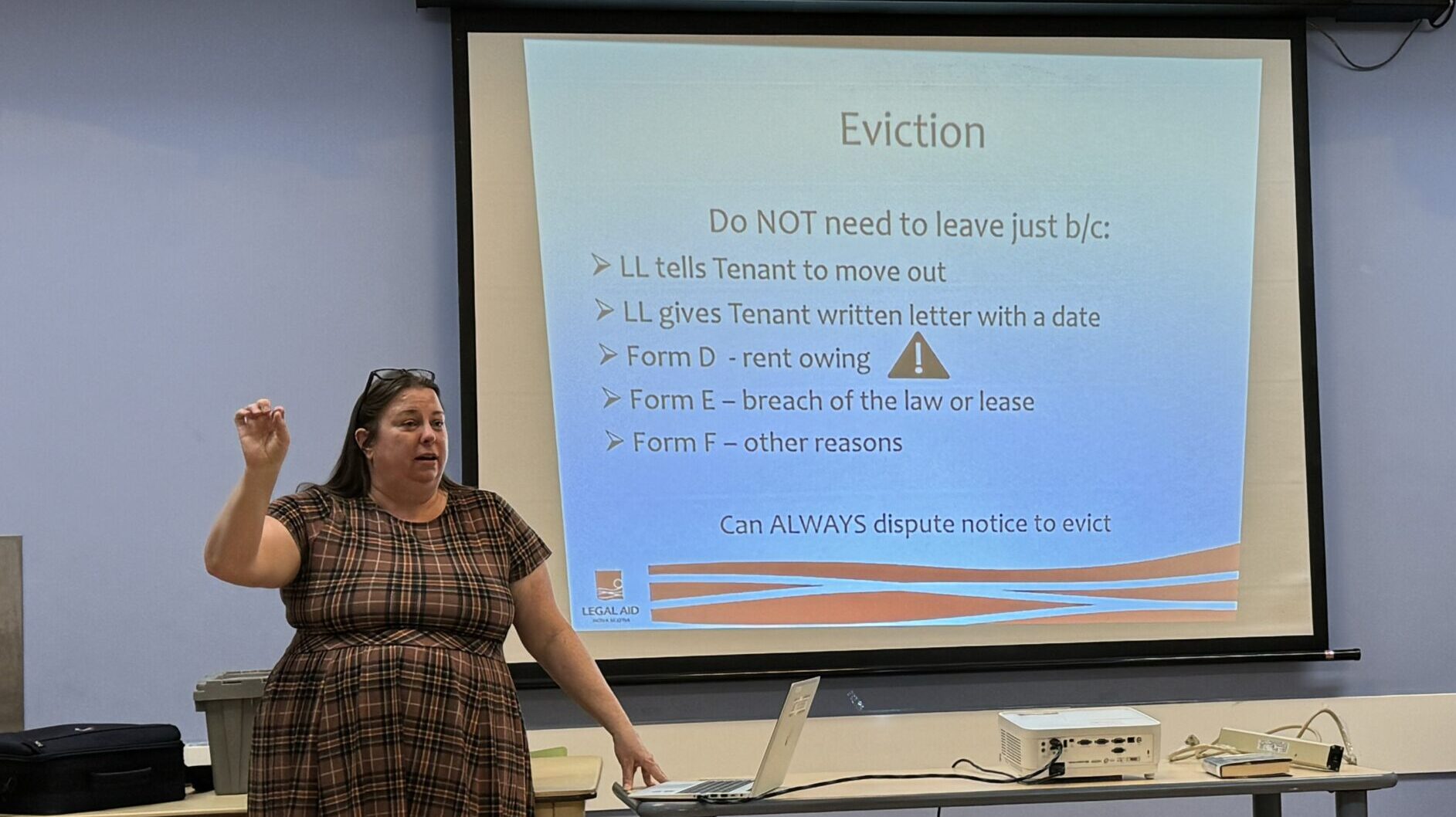

caption

Tammy Wohler speaks about the Residential Tenancies Act at a free information session.In a housing crisis, it’s critical that tenants know their rights, says the managing lawyer of the social justice office at Nova Scotia Legal Aid.

Tammy Wohler, a managing lawyer of the social justice office at Legal Aid Nova Scotia, said residential tenancy-related applications account for 65 per cent of her office’s files.

“There is a lack of available units and the units that we have are unaffordable,” she said. “We don’t have enough deeply affordable housing and the measures being taken are just not sufficient right now.”

The provincial government raised its cap on residential rent increases to five per cent in January. But for tenants in fixed-term leases, the move offers little security. These leases allow landlords to increase rent by more than five per cent, so long as they have new tenants.

This makes it harder for tenants to find a permanent place to live and easier for landlords to dodge the rent cap.

It’s a situation Wohler says is causing problems for renters who may not understand their rights under the Residential Tenancies Act (RTA).

Wohler hosted a free tenants information session at Captain William Spry library last week. She said hosting information sessions are important because she often sees applicants when it’s too late to avoid unnecessary stress.

She said tenants often come to her after an order under the tenancies act has resulted in a small claims court case. At this point, some applicants want to appeal to the Supreme Court.

“Had I been involved from the very beginning, I may have avoided that very first order.”

The rental market can be difficult to navigate in the best of times but it’s even more challenging in a housing crisis. Legal Aid Nova Scotia provides free legal services to people in need. At the information session, Wohler reviewed the key points in the act.

The act outlines the law governing landlords and tenants to protect both parties. It has information about conflict resolution, security deposits, evictions and more. It’s long but Wohler said that knowing your rights is critical.

Here’s a starting point:

Lease types

Before signing a lease, Wohler stressed, it is important that renters understand the difference between a fixed-term and periodic lease.

“The fixed term lease is a significant problem that we’re running into, where someone is trying to get into their forever home, or close to forever home, and they can only get any place for a year and there’s no guarantee past that,” she said.

A fixed-term lease is used for a given period of time with a specific start and end date. A periodic lease, however, renews automatically — on a yearly, monthly or weekly basis. Since the fixed-term lease has an end date, the tenant is not guaranteed a place to live after that date.

“Unfortunately, the fixed-term lease loophole, as I call it, is being used to evict an otherwise upstanding tenant who’s paid their rent on time and is otherwise perfect,” said Wohler.

Security deposits and guarantee agreements

Landlords often request a security deposit. According to the act, a security deposit cannot be more than the cost of half of one month’s rent. The security deposit should be returned to the tenant within 10 days of the lease ending.

A landlord cannot make a claim for cost damages that are considered wear and tear. Wear and tear is defined as the typical extent of depreciation after a given period of time.

Landlords are required to file a security deposit claim form if they wish to claim a portion or the entirety of a tenant’s security deposit. This form must be submitted in person at Access Nova Scotia within 10 days of the termination of a lease.

Wohler encouraged attendees of the information session to not only know what is in the lease before signing but to ensure the unit actually exists.

“There’s a lot of scams out there now,” she said.

She said it is important to ensure such details as whether pets or children will be living in the unit are indicated in writing and on the lease.

Forms

Tenant-landlord matters are often handled through written documents — templates of forms outlined in the tenancies act.

Form P is the standard lease form, which landlords can use as the residential lease agreement for their tenant to sign.

Form DR5 is used by landlords if they wish to end a tenancy because they plan on demolishing, repairing or renovating a property when both parties agree. In this situation, a tenant is entitled to compensation. A tenant in a building of four or fewer units is entitled to compensation of one month’s rent while tenants in buildings with five or more units is entitled to three months’ rent.

Form D, a kind of warning, is a landlord’s notice to end a tenancy agreement when the tenant has not paid rent. A Form D can be given to the tenant after their rent is at least 15 days late. If the tenant pays rent after receiving a Form D, the notice is set aside.

If a tenant does not pay rent or leave the premises, a landlord can file a non-hearing eviction by using a Form K, an application to the director of residential tenancies.

Another conflict-resolution form is Form J. Both landlords and tenants can submit a Form J and an application to the director can be made up to one year after a lease has ended.

Form F is used by landlords to give their tenants a notice to quit for reasons other than failing to pay rent or abiding by statutory conditions. Landlords can use a Form F in a few situations, including if the tenant is putting the safety or security of the landlord or other tenants in the same building at risk.

In all these cases, landlords must use the required form for each specific situation.

It’s important to know that Nova Scotia does not have an agency overseeing residential tenancies. This means that if the director makes an order to a landlord or a tenant, the order is not enforced by the government.

Wohler said, “I think one of the important things to know is that a lot of notices are not binding … if you’re given a nasty letter by a landlord to get out, you don’t need to listen to that.”

She said the current housing crisis puts most tenants on an “unequal bargaining ground.” Knowing tenant rights and that resources such as Legal Aid exist, is essential, she added.

However, Wohler also acknowledged that not all landlords are making a profit.

“There are a lot of small landlords that are struggling with the increase in cost,” she said. “But at the same time, if you’re in the business of providing housing, you’re providing homes and I think people need to recognize that.”

About the author

Raeesa Alibhai

Originally from Toronto, Raeesa Alibhai is in her fourth-year of the Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) Program at King's. She is fond of all forms...