In digital communication age, people go ‘no contact’ to deal with conflict

Beckham celebrity drama sparks conversations on cutoff culture

caption

Charvi Gambhir shares her experience getting cut off by a friend of ten years.Brooklyn Beckham isn’t the only one cutting ties with his loved ones. This week, Dalhousie students shared their experiences of going ‘no contact’ and how it’s affected their personal relationships.

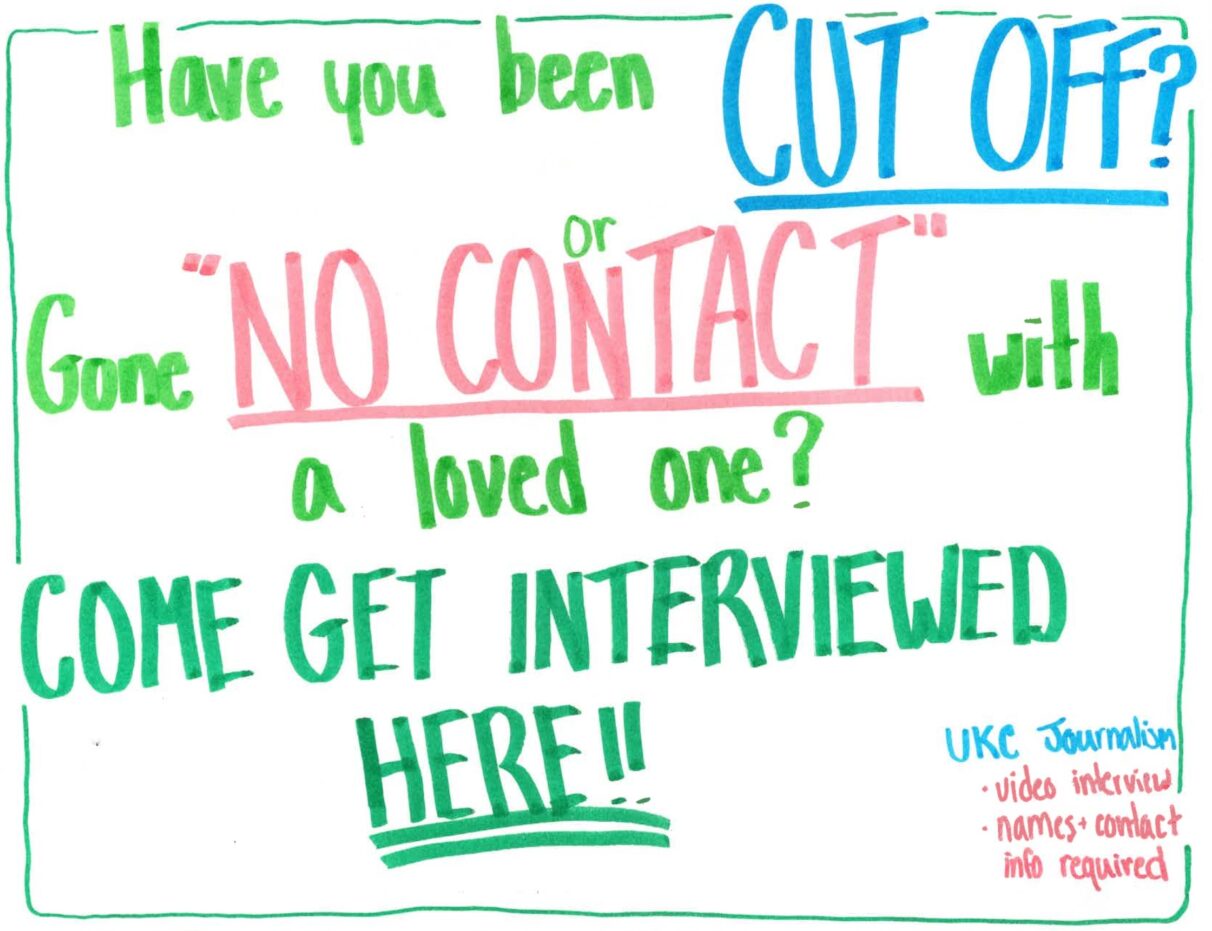

caption

This handmade sign was posted at the Dal SUB earlier this week and served as a call for interview subjects.

The eldest Beckham son recently made headlines for cutting ties with his parents, citing inauthentic family relationships and inappropriate behaviours from his mother Victoria, the former Spice Girl now married to soccer superstar David Beckham, as the cause.

The celebrity family feud has sparked online discussion on Gen-Z’s willingness to disconnect from those deemed toxic in their lives. These cutoffs, which involve blocking on social media and going no-contact, are often backed with online support from young peers.

Cornell University human development professor Karl Pillember told the Cornell Chronicle in 2020 “that 27 per cent of Americans 18 and older had cut off contact with a family member, most of whom reported that they were upset by such a rift.”

This upset is a familiar feeling for people like Charvi Gambhir. Her decade-long friendship came to an abrupt end following tensions during the pandemic. She said the cutoff was painful for her.

“I was crying for a very long time,” said Gambhir. “I did reach out when I was coming to Canada. I was like, ‘Hey, do you want to meet up?’ He said no, and I was heartbroken.”

Gambhir was eventually able to get a response from the friend who had cut her off.

Many others never end up hearing back at all. Dalhousie theatre student Alex Robichaud and his relatives were cut off by a close family member. He said he hasn’t seen them in person in over two years.

“I’m really frustrated,” said Robichaud. “This is someone I’ve been close to my whole life, and then all of a sudden without any sort of warning, just complete silence.”

For many, these disconnects can be difficult to handle, but Dalhousie University computer science student Aditya Lad says that there’s always two sides to a story. Lad has been on both ends of a no-contact situation.

From his past experiences of being cut off, he’s been able to understand the perspectives of those who chose to eliminate people from their social spheres.

“People like convenience. Everybody likes their safe bubble,” said Lad. “They don’t want to break that. So, they just don’t try to understand what’s going on on the other side and it leads to situations like that.”

Social media’s simple methods of blocking has made it easier than ever to create curated spaces with only people who agree with each other.

In turn, the shift to digital spaces has greatly affected how people communicate. Dalhousie psychology professor and author of the book The Power of Guilt: Why We Feel It and Its Surprising Ability to Heal, Chris Moore has spent years studying developmental and social psychology. He says that nonverbal cues that are crucial in our communication have been lost in online spaces.

“There is a richness in natural human communication that just doesn’t exist in online communication,” says Moore.

“Social media allows more definite or final forms of resolution. For example, just ghosting or blocking, those kinds of things would just bring an end to a relationship, which normally would not happen in a natural face-to-face environment.”

Leave a Reply