Indebted: The growing weight of Canada’s education system is crushing international students

caption

Rishabh Desai, an international student from India, came to Canada for two years, but left for home within four monthsCanada has relied on international students to keep its colleges and universities afloat, international students are now asking what's it worth to them.

Rishabh Desai, an international student from India, was only seven days into his Canadian experience when he realized Canada is not what he expected it to be.

Desai landed in Toronto from India on Aug. 21, 2022, and was scheduled to join Dalhousie University in Halifax for his master’s in public administration program. At the Toronto Pearson Airport, on the day of his flight to Halifax, he did not board the plane. Instead, he dropped out of the master’s program he had already paid for in full.

When at the bustling airport, 11,500 kms away from home, Desai stood alone and cold. One thought occupied his mind – he did not have a place to live where he was supposed to land.

“I was visibly traumatized, but I didn’t even have the time process all of those feelings,” Desai said.

With no long-term rental arranged, he had a hotel stay booked for two days at the Hampton Inn, Halifax. He thought finding a place while being physically present in the Maritime city would bring better results. After scouring through each possible avenue available to him in his first week in the country, he knew it would take more than a couple of days to find a place to live. That’s when the severity of Halifax’s housing crisis hit him. During his Uber ride to the Pearson airport, he discovered he couldn’t even extend his hotel stay beyond two days. Desai lost hope and figured going to Halifax would be hopeless.

“I was quite starry-eyed. I was hopeful of my life in Canada, I was looking forward to my life in Halifax. It was the perfect life that any new international student could have, but then, all of it just fell apart.”

Halifax’s one per cent vacancy rate for rental apartments in the 2021 Rental Market Survey by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation ranked the second worst in Canada. It showed no change in 2022. Desai was one of a growing number of international students in Halifax struggling to find a place to live.

A quarter of Dalhousie University’s 20,000 students are international students. Desai’s plea to set up online classes for him until he found accommodation was rejected by Krista Cullymore, the program manager at Dalhousie’s School of Public Administration.

Cullymore refused to comment about Desai’s requests.

“I work only for the School of Public Administration and am not the spokesperson for the school,” she wrote in an email.

Janet Bryson, associate director of media relations at Dalhousie University, wrote in an email that the university has dedicated spaces to support international students.

“As for supports for students, international students at Dalhousie have dedicated support through the university’s International Student Centre.”

For Desai, the International Student Centre at Dalhousie University provided no help.

More and more international students

Canadian universities are accepting a growing number of international students and many of the students, experts and advocates interviewed for this story say international students are left to fend for themselves to find basic services such as housing. Critics say universities need to do a better job accommodating these students who pay substantially higher tuition fees that are being used to compensate for provincial cutbacks to education.

Dalhousie University accepts more than 4,700 international students, 24 per cent of its students. In the 2019-2020 academic year, Dalhousie students came from more than 132 different countries. Over the past decade, the international student population has more than doubled at the university — a 128 per cent increase.

In the first quarter of 2022, Canada had its largest number of international students enrolled in post-secondary institutions, surpassing its previous best, in 2021, by 32 per cent.

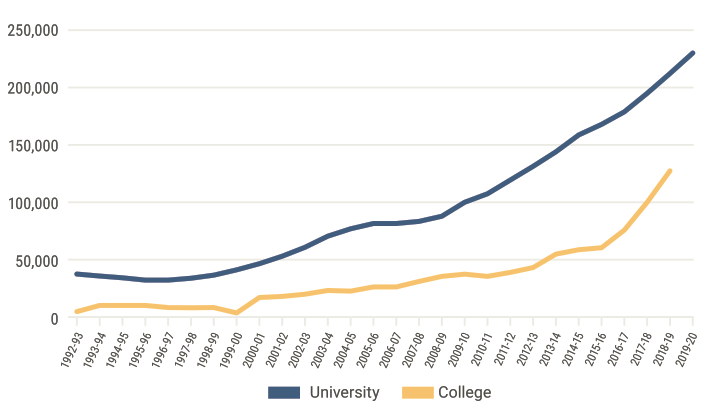

caption

International student enrolments from 1992-93 to 2019-20 in colleges and universities in Canada.Half the country’s international students attend Ontario universities. When domestic student enrolments decline, an increasing number of international students keep paying institutions at double or triple the rate of their domestic counterparts. Universities and colleges depend on these higher tuitions to compensate for decreased provincial funding.

Ontario’s auditor general 2021 report on public college oversight said between 2012 and 2020, colleges in Ontario experienced a 15 per cent decline in domestic student enrolments but a 342 per cent growth in international student enrolments. The auditor general’s report concluded, “Public colleges are increasingly reliant on tuition fees from international students to remain financially sustainable.”

Last year, colleges in Canada received $1.7 billion in tuition fees from international students, 68 per cent of total tuition revenue.

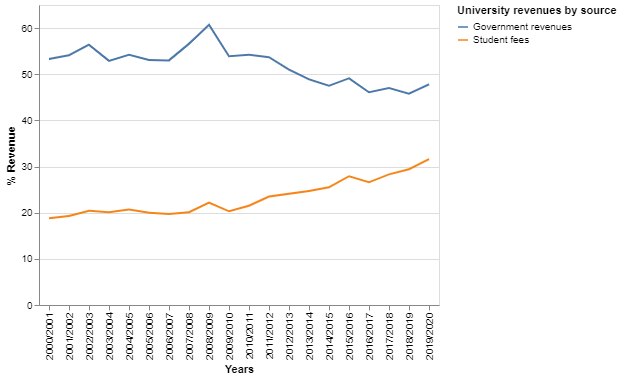

In 1982, government funding of Canadian universities comprised 82.7 per cent of university operating revenues. In 30 years, that percentage went down to 54.9 per cent.

A 2020 report by Higher Education Strategy Associates, a Toronto-based consultancy, notes that since 2012-2013, funds from international students in Canada have covered slightly more than 100 per cent of the collective increase in university operating budgets. “Every faculty member at every institution who saw their pay rise in the last five years did so because of international students,” the report read.

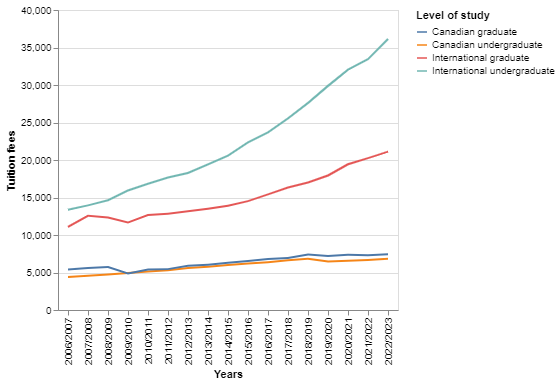

caption

Canadian and international tuition fees by level of studyDalhousie University’s revenue from tuition fees surpassed its government funding for the first time in 2022-2023.

According to Statistics Canada, from 2010-2011 to 2020-2021, as a percent of total revenue, tuition revenues went up from 21.5 per cent to 28.8 per cent, while provincial funding declined from 41.5 per cent to 32.5 per cent in the country.

caption

University revenues from 2000/2001 – 2019/2020With Quebec holding the highest provincial funding to post-secondary institutions in Canada, the national average is only a part of the picture. For some provinces, the funding has plummeted more harshly.

Over the last 10 years, when adjusted for inflation, all provincial government’s except Quebec have shown a negative expenditure for education on the government’s part.

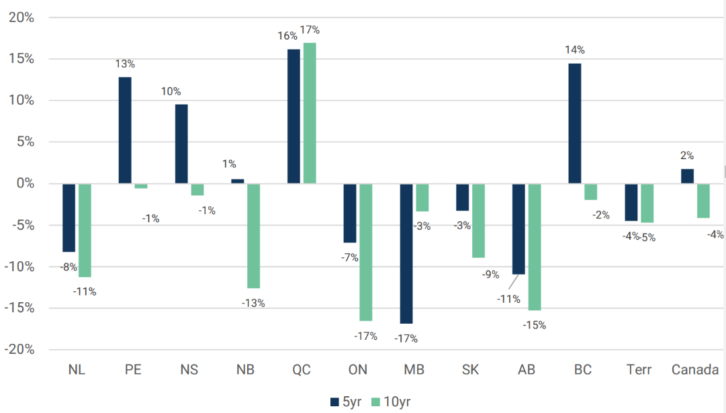

caption

Changes in Provincial Transfers to Institutions by Province over Five and Ten Years, to 2020-21, in $2020.Graham Barber, assistant director of international relations at Universities Canada, a membership organization providing university presidents with a unified voice for higher education, research and innovation, said the reduction of funding at the provincial and the federal level leaves a hole in university budgets, but the universities have been quick to adapt in innovative ways like commercialization of research or getting involved in entrepreneurship spaces.

“Universities are doing all they can with the money they are receiving, but they’re looking for other avenues, of course to keep their operational budgets and international student fees are definitely one of those and they’re probably a larger share of it,” he said.

The Ontario government and the Ontario Ministry of College and Universities did not respond to multiple requests for comments on cuts to provincial funding to post-secondary education.

Tuition and services

Desai was required to pay his first year’s tuition fees – $14,000 – in full as a prerequisite for his visa approval. According to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, most international students must have a $10,000-deposit in a Guaranteed Investment Certificate in Canada and their first year’s tuition fees paid to be approved for a student visa.

Like most international students, Desai paid almost three times the tuition that a Canadian student paid.

Tracy Smith-Carrier, Canada Research Chair in Advancing the UN Sustainable Development Goals, wrote a piece for the Canadian Association of University Teachers that talked about concerns with lower government funding to institutions. She said the discrepancy in fees causes all sorts of inequities.

“In a country where we supposedly care about inequities, this is something we need to address… They [international students] are paying a tremendous amount for their education, and they are not getting the support they need once they are here.”

In 2021, Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ont. declared insolvency. The 9,000-student university expected to enrol 1,000 international students by 2024 and over-spent in anticipation. Smith-Carrier believes that the failure to attract the expected number of international students resulted in the university’s downfall; she said the “government abandoning the sector” is concerning. “Putting all of our eggs into that basket of international students can be very tricky for the long-term,” she said in an interview.

Ross Romano, Ontario’s minister of Colleges and Universities in 2021, said in a statement then that the university’s insolvency was unprecedented.

“The government wants to ensure this issue does not repeat itself in other institutions.” He said, “The government will be exploring its options, which could include introducing legislation to ensure the province has greater oversight of university finances.”

While increases in domestic student tuition falls under provincial jurisdiction, international students’ tuition is unregulated and is subject to the will of a university’s administration. For instance, in Nova Scotia, 10 universities have a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Advanced Education that caps undergraduate domestic tuition increase at three per cent each year. But there is no such provision or law defined for international students that caps the increase in tuition fee. According to Statistics Canada, international tuition fees in Canada increased by an average of more than 35 per cent over the past five years.

Dalhousie, the largest post-secondary institution in Nova Scotia, announced in its 2023 plan that it would implement a guaranteed fee model from this year. This would mean international undergraduate students would pay a fixed pre-decided tuition price each year: tuition would not increase or decrease.

But there is a catch – the model would mean an average increase of 27.21 per cent across programs for incoming international students, as opposed to a three per cent increase in tuition for domestic students.

The plan states Dalhousie’s current international tuition rates are significantly lower than at similar Canadian universities. “This gap undermines perceptions of the quality of our programs and our [international] student experience,” the 2022 release read.

The university’s recommended budget for 2022-2023 cuts funding for international student services by 21.51 per cent.

Bryson at Dalhousie University wrote in an emailed response that the university would gain largely from the new tuition structure for international students.

“This new approach will enable Dalhousie to make significant investments in our student experience including increased funding for scholarships and bursaries, additional student supports, and improvements to academic buildings and learning spaces,” according to Bryson’s email.

Bryson did not respond to specific questions about the increase in tuition fee or to allegations of inadequate international student support at the university.

Muyu Lyu, president of Dalhousie’s International Student Association (DISA), said that the money international students pay bears no fruit for them.

“We pay for the whole campus,” he said, “and that’s the issue. When you increase tuition without an increase in service, that’s not ethical.”

International student needs differ

In 2021, 35 per cent of international students in Canada were from India, 17 per cent from China, four per cent from France, three per cent each from Iran, South Korea, Philippines, and Vietnam, and others from more than 110 different countries.

The International Support Centre at Dalhousie employs two immigration advisors to serve 4,700 students. “That’s pretty much all the international support services we have for international students,” Lyu said.

Barber at Universities Canada, said universities offer several services for international students including housing support, immigration counselling, mental health support, and paperwork services.

“Our universities are doing the absolute best they can to serve international students and make sure they feel welcomed.”

When Desai couldn’t find a place to live in Halifax, he moved to Waterloo, the only place in Canada he could find shelter, albeit at a relative’s place. Desai enrolled at University of Waterloo for a completely different course that he did not want to pursue in the first place.

“It was a split-second decision, and everyone from my family was disappointed with how the situation turned out to be,” he said.

But even in a new city, he struggled to make ends meet.

Desai’s chequing account, at its lowest in October last year, dropped to $10. His stomach was often empty with one meal a day.

The 2021 National Student Food Insecurity report by Meal Exchange, an Ontario-based research organization, found 74.5 per cent of international students in Canada were food insecure. The only group facing a higher percentage of food insecurity – 82.4 per cent – was exchange students, foreign students who come to study in Canada for shorter periods of time also international students.

“During the [first] two turbulent months, I was just having one meal a day … not even a proper meal,” he said.

caption

Rishabh Desai, is now back in India, completing his postgraduate studies from home.According to Statistics Canada, the median annual income of international students in 2018 was $9,500. On an average, an international student would end up paying more than 84 per cent of their income to cover rent. Statistics Canada recommends people should not pay more than 30 per cent of their income on rent.

The average food expenditure in Ontario amounted to $10,311 per year per person in 2022, leaving international students with not enough money to be able to afford food.

After a month’s stay at his relative’s apartment, Desai moved to a new place. He then moved several more times, living in four houses in two months. At one point, he shared a two-bedroom apartment with six other people and hesitated to call it home.

“All of us understood the struggles that all of us had to go through to get that house,” he said, “but, it gets uncomfortable, especially when there’s just one washroom.”

The Canadian Rental Housing Index by BC Non-Profit Housing Association mentions that Waterloo would need 995 more affordable rooms to accommodate the lowest income group (household income of less than $23,284). “The housing struggle is casting a dark shadow over lots of people’s experiences in Canada,” Desai said.

Sharom Rho, an organizer with Migrants Students United, a branch of the advocacy organization Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, an Ontario-based NGO, said universities and colleges bring in tens of thousands of international students even as they know there is not enough on-campus housing. “It’s common for international students to be living 4-7 people in one basement sharing one bathroom.”

The Canadian Bureau of International Education’s 2021 international student survey said 79.2 per cent of the respondents chose Canada because of its safety and stability.

Three months into his Canadian experience, Desai has faced food insecurity, exploitative employment practices, and a housing crisis – none of which he had faced in India, a developing country.

Desai’s mother, Aditi Patel, thinks how her son was treated was unfair, and the Canadian dream is a lie.

“Canada was more of a glorified picture… A lot of radical changes are required by the government with respect to the international students. They blindly come to Canada but that doesn’t mean they need to be exploited.”

Desai’s struggles began with Dalhousie and the lack of affordable housing in Halifax, then shifted to Waterloo, where he thought life would be less expensive. Unfortunately, he was fighting a losing battle of high tuition and living expenses – hallmarks of many cities in Canada that are home to colleges and universities.

Once certain about his future in Canada, Desai is not sure anymore. He decided to return to India after only four months away. He is now almost a year into his two-year master’s program but is required to return to Canada this year to complete an internship that’s a part of his program.

Desai remembers the sad feeling of being cold alone, uncertain about his future, standing at the Pearson Airport waiting for this flight back to India. It was the day before last New Year’s Eve.

“I am glad to be back home,” he said.

About the author

Shlok Talati

Based in Toronto, Shlok Talati is a 2023 CBC News Donaldson Scholar with experience in radio and digital. He holds a master of journalism from...

C

Carlo